数据库

- 开放数据标准:Postgres,OTel,与Iceberg

- 数据库老司机:文章导航

- 小数据的失落十年:分布式分析的错付

- OpenAI:将PostgreSQL伸缩至新阶段

- Etcd 坑了多少公司?

- AI时代,软件从数据库开始

- MySQL vs PostgreSQL @ 2025

- 数据库火星撞地球:当PG爱上DuckDB

- 对比Oracle与PostgreSQL事务系统

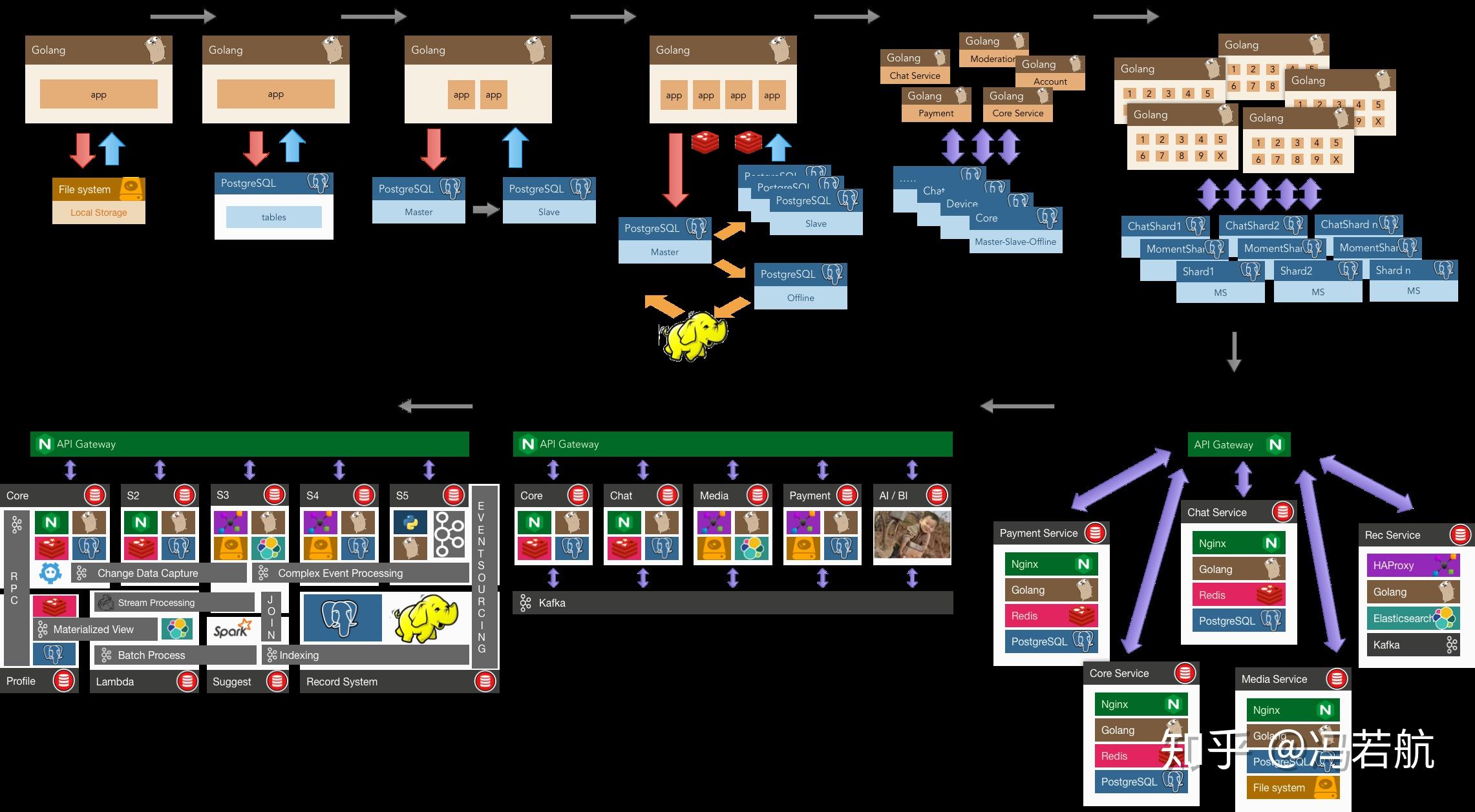

- 数据库即业务架构

- 七周七数据库(2025年)

- 自建Supabase:创业出海的首选数据库

- 面向未来数据库的现代硬件

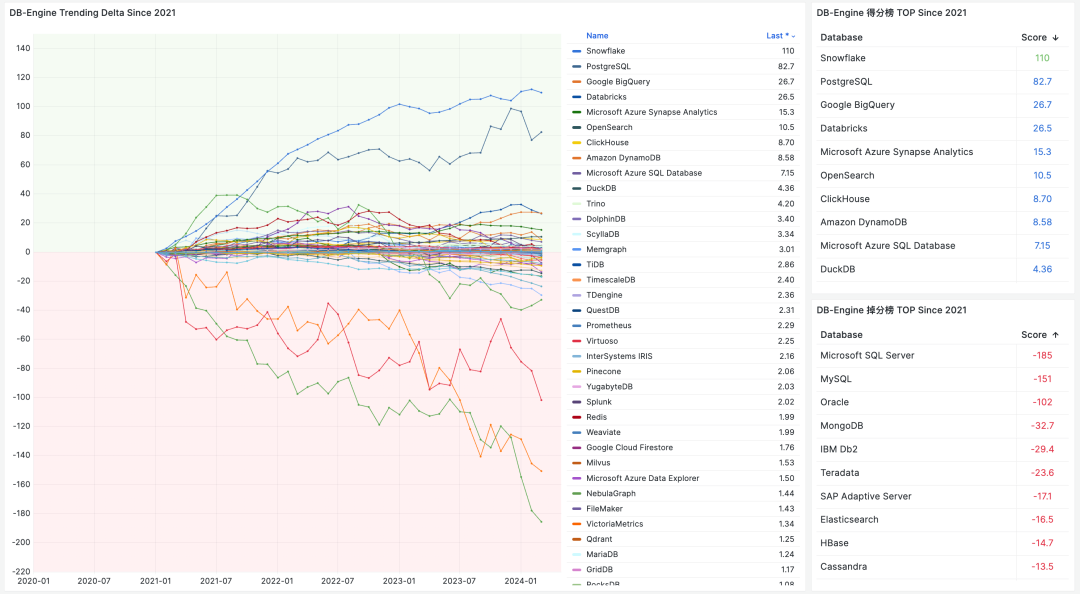

- PZ:MySQL还有机会赶上PostgreSQL的势头吗?

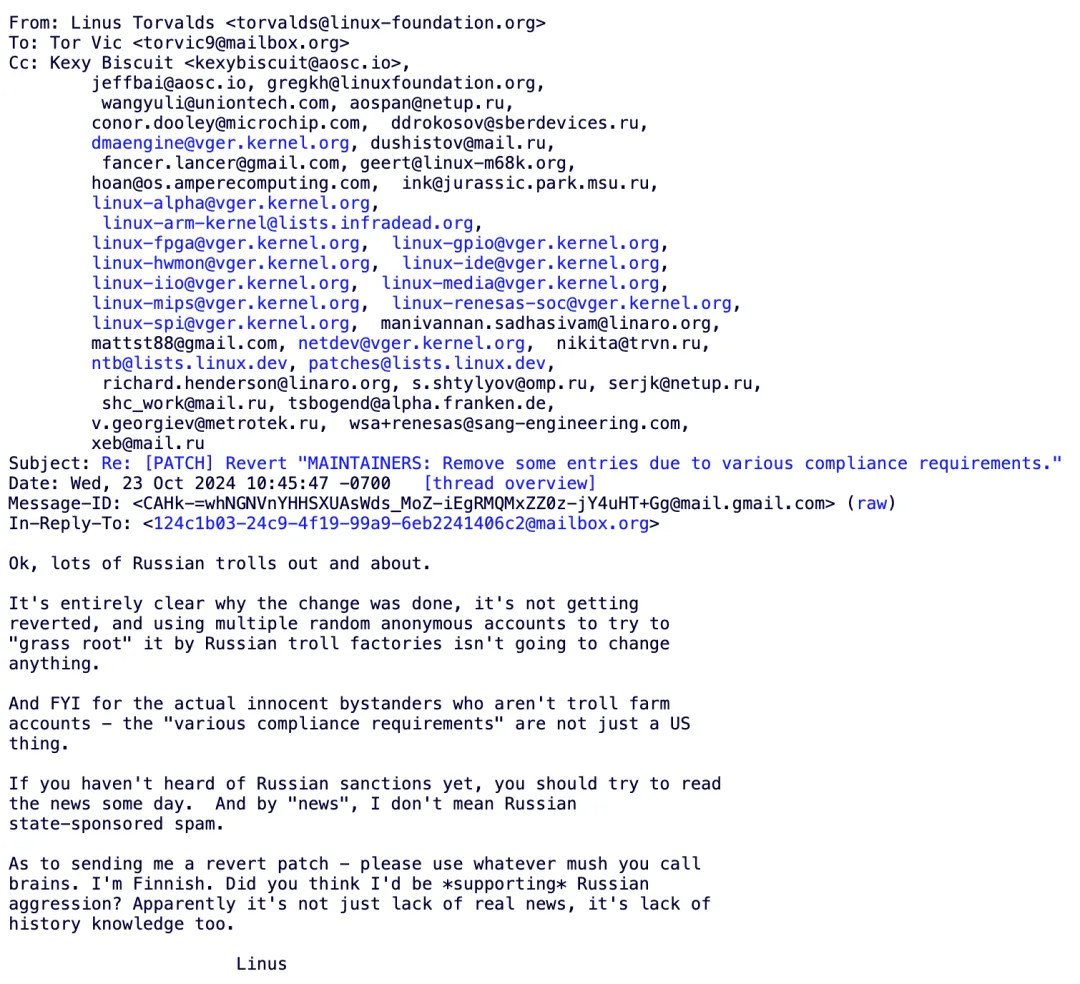

- 开源“暴君”Linus清洗整风

- 先优化碳基BIO核,再优化硅基CPU核

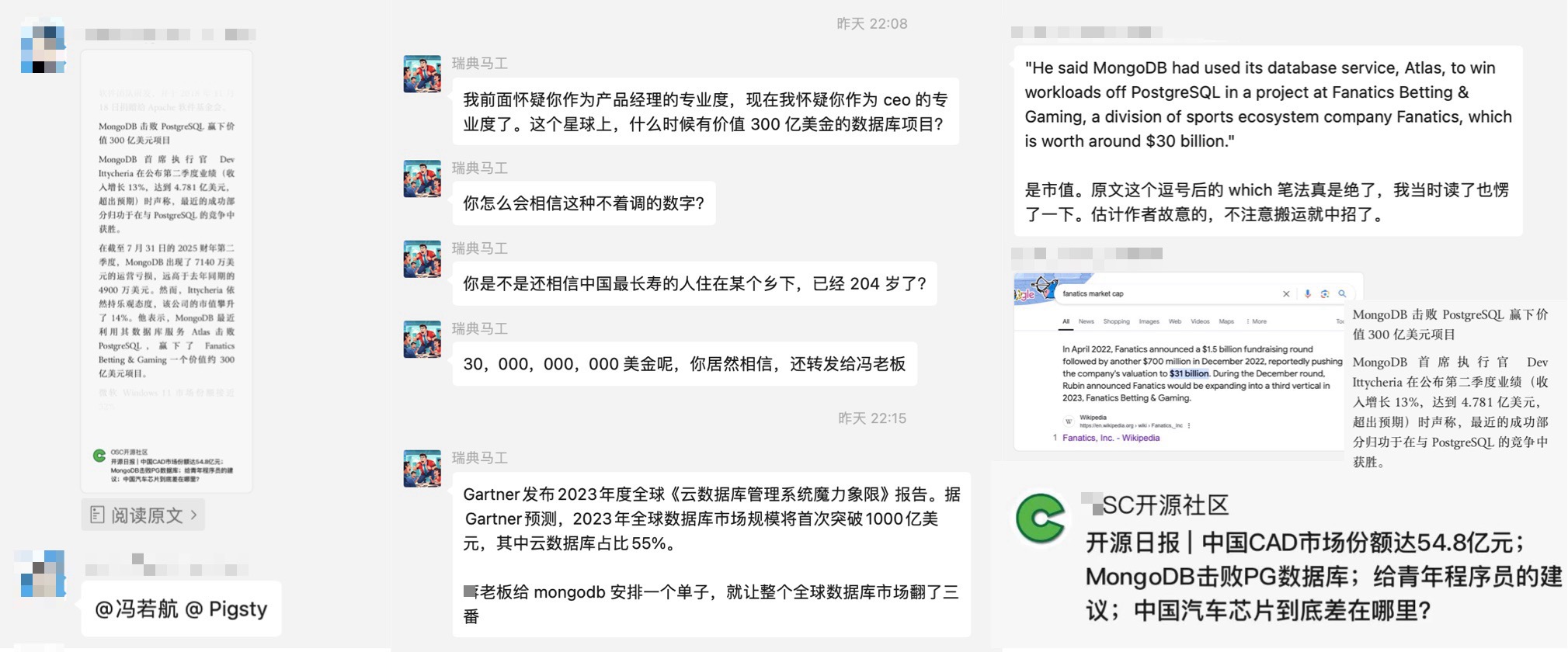

- MongoDB没有未来:好营销救不了烂芒果

- MongoDB: 现在由PostgreSQL强力驱动?

- 瑞士强制政府软件开源

- MySQL 已死,PostgreSQL 当立

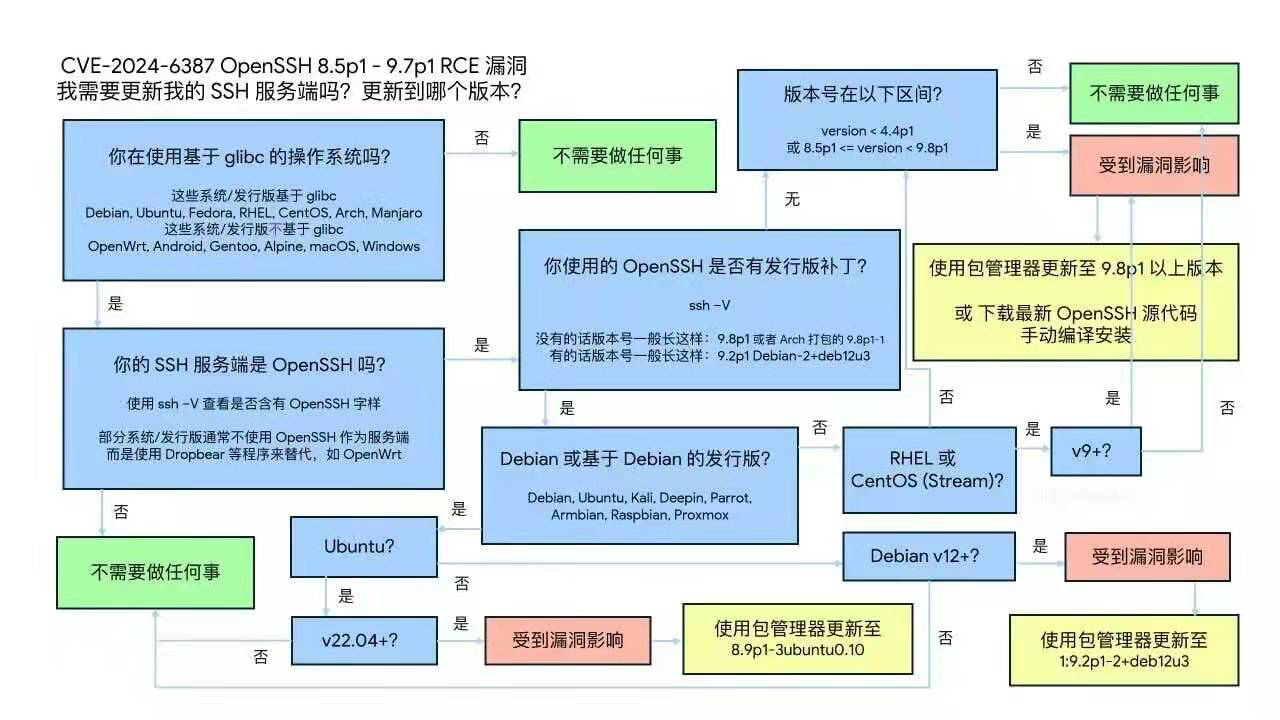

- CVE-2024-6387 SSH 漏洞修复

- Oracle 还能挽救 MySQL 吗?

- Oracle最终还是杀死了MySQL

- MySQL性能越来越差,Sakila将何去何从?

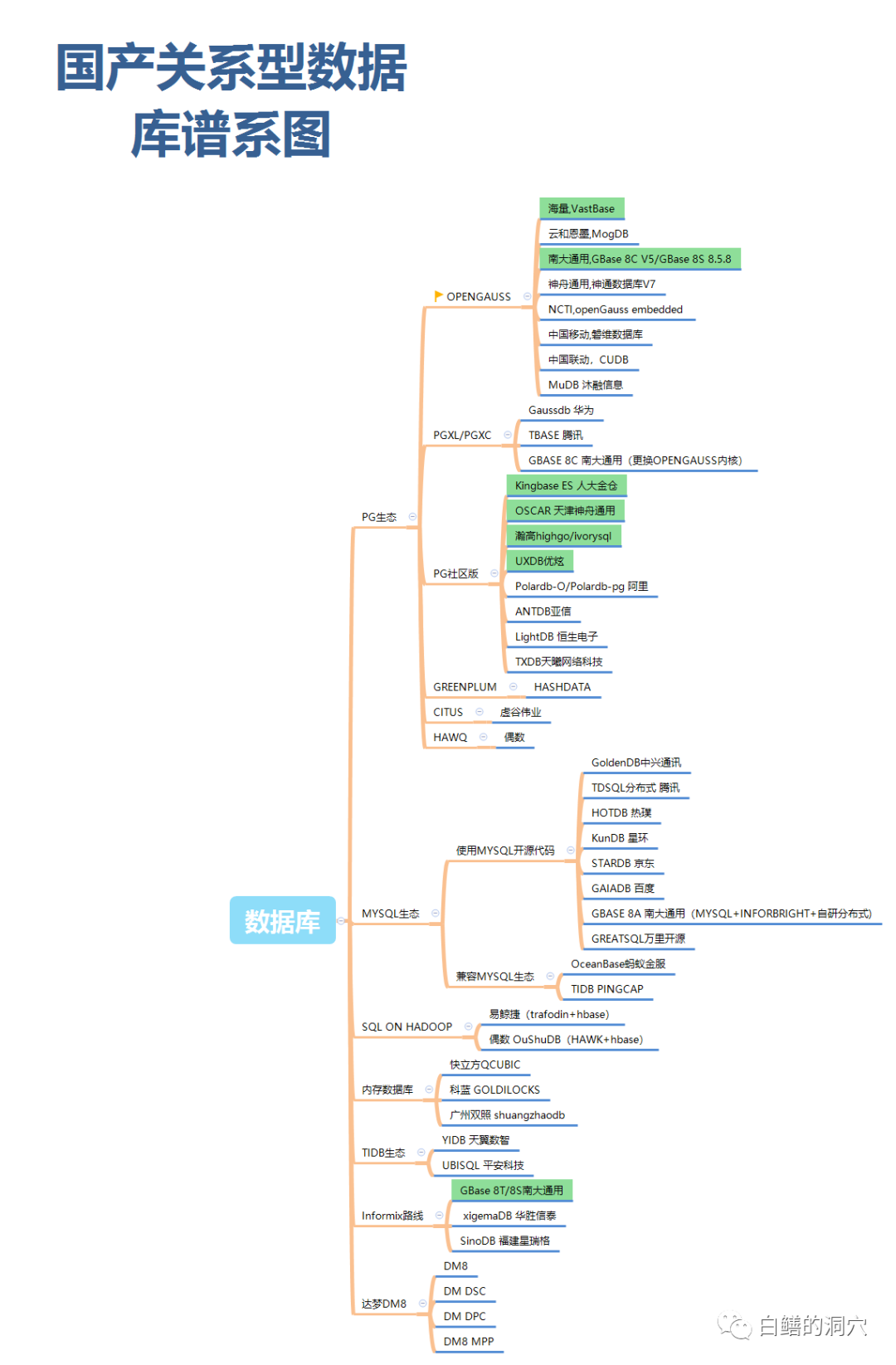

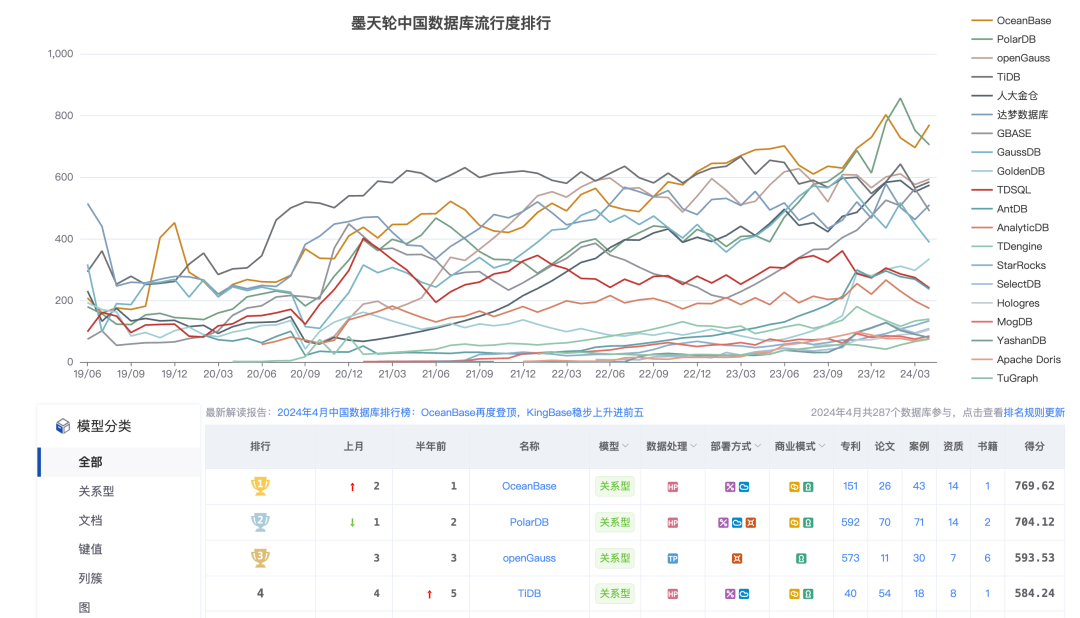

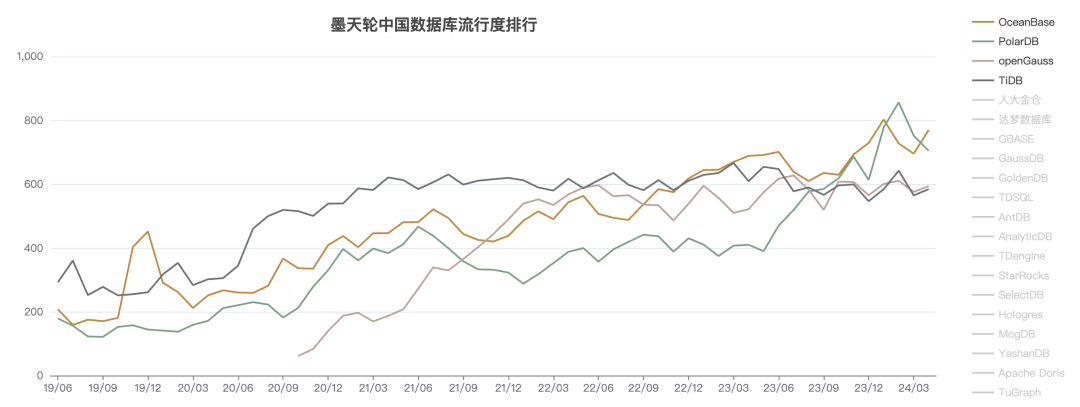

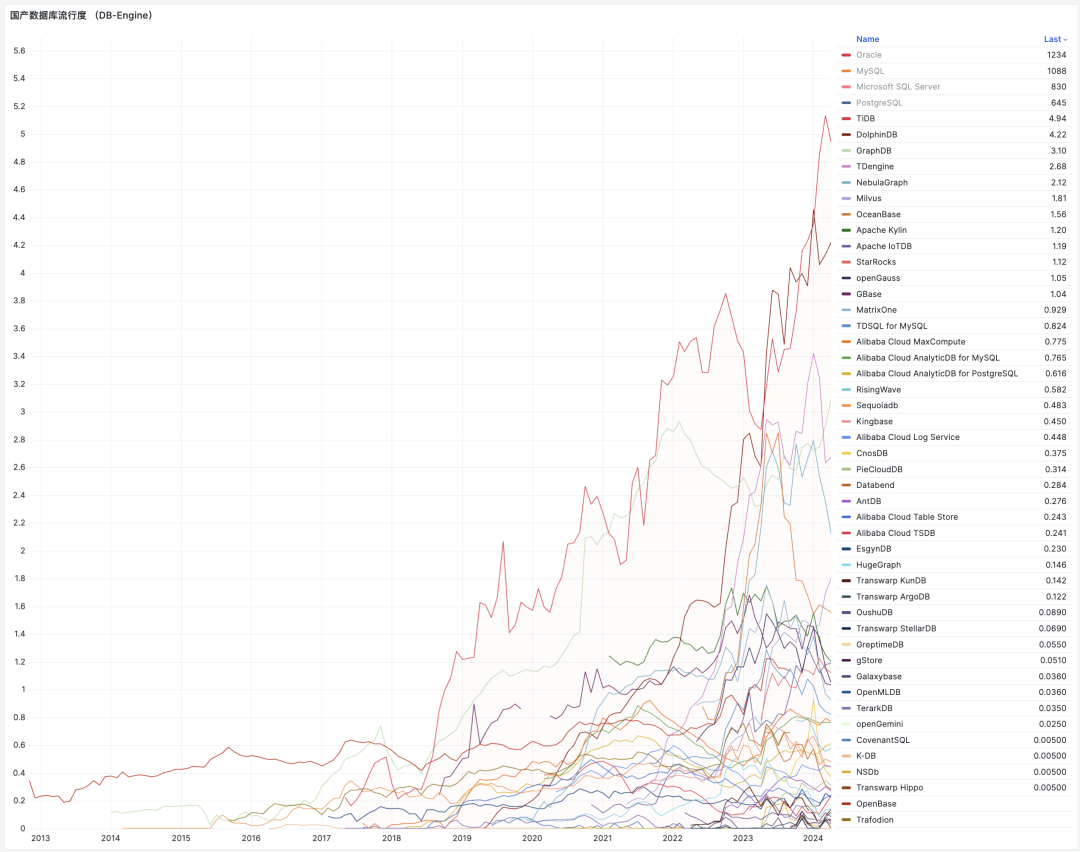

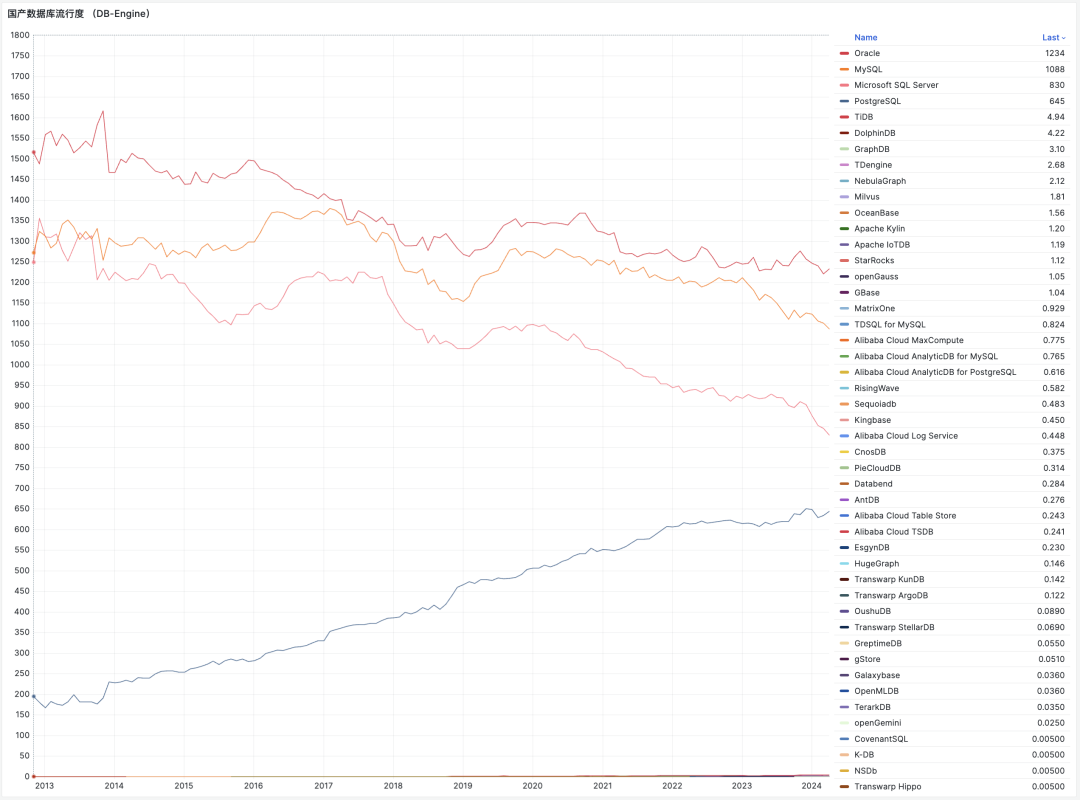

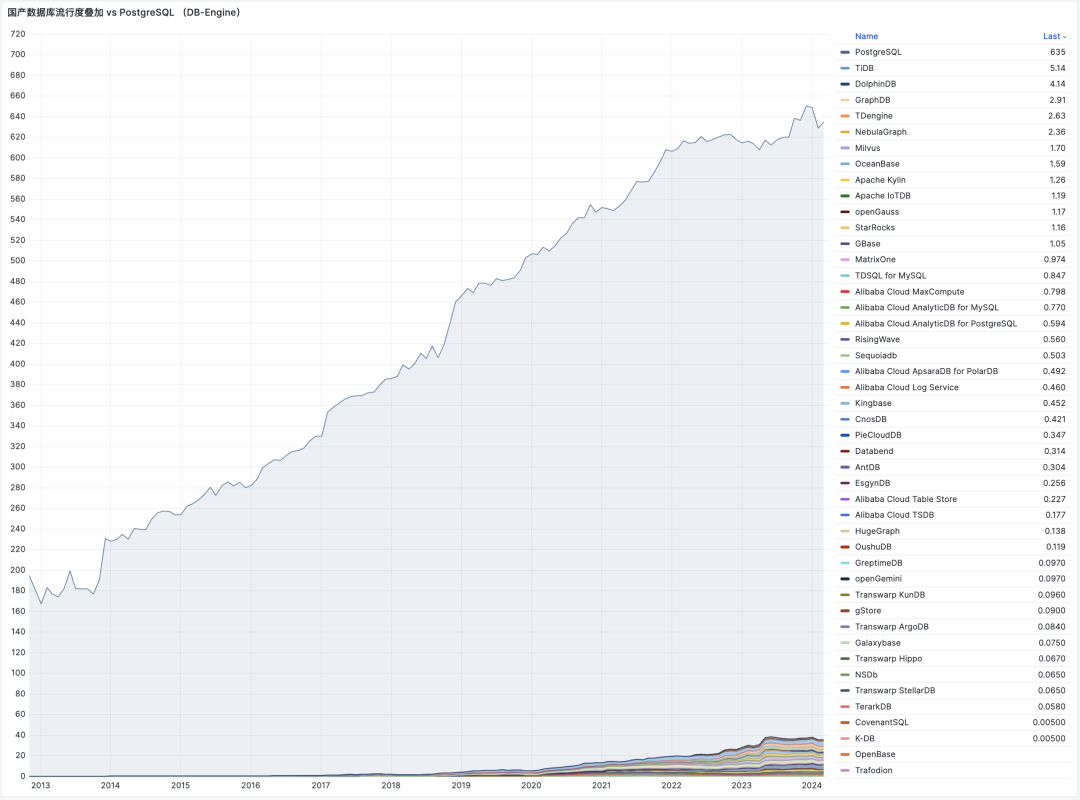

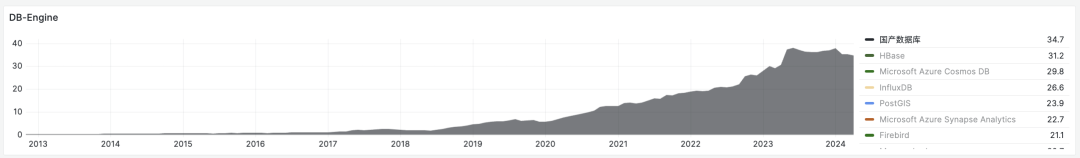

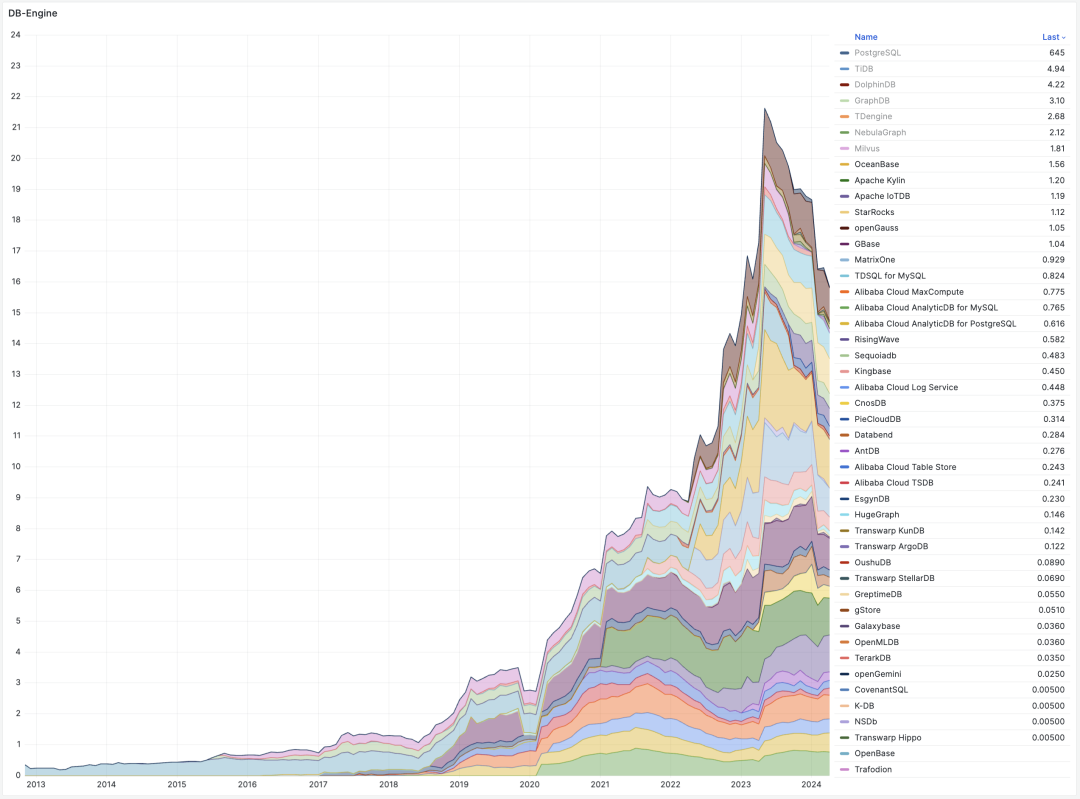

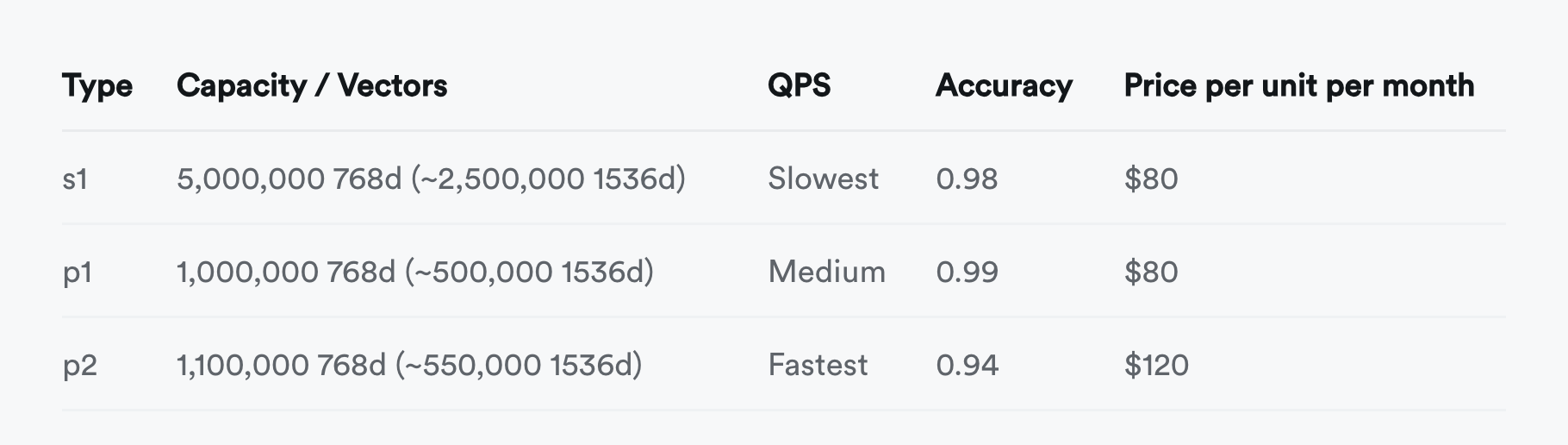

- 国产数据库到底能不能打?

- 20刀好兄弟PolarDB:论数据库该卖什么价?

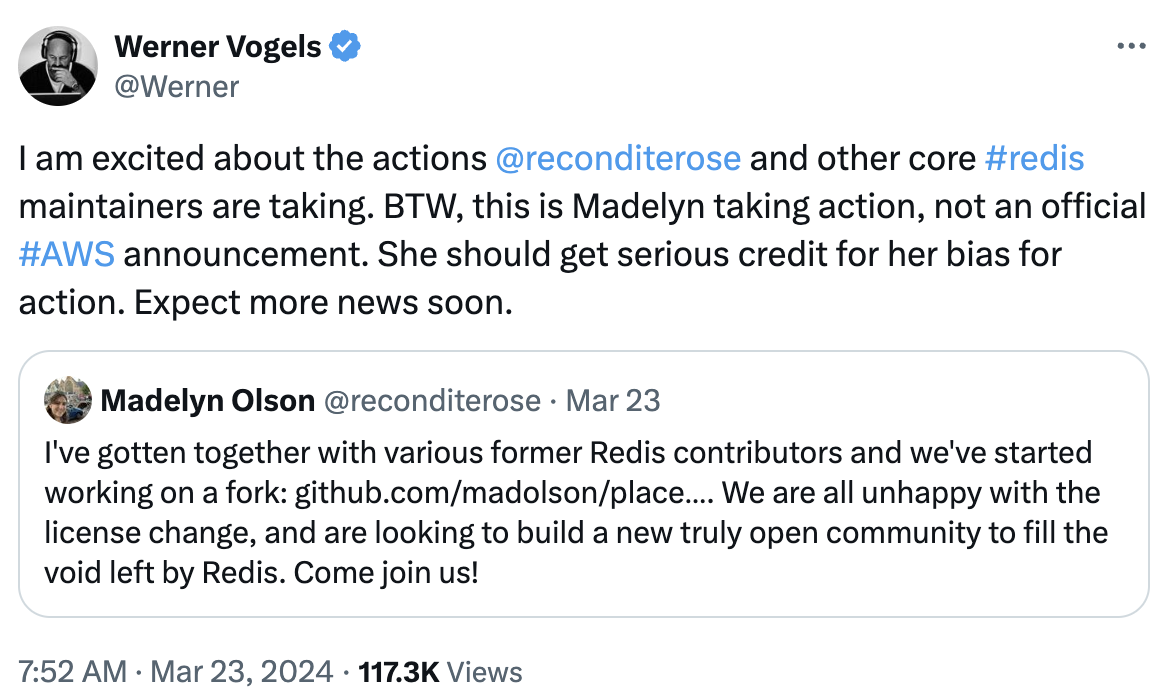

- Redis不开源是“开源”之耻,更是公有云之耻

- MySQL正确性竟如此垃圾?

- 数据库应该放入K8S里吗?

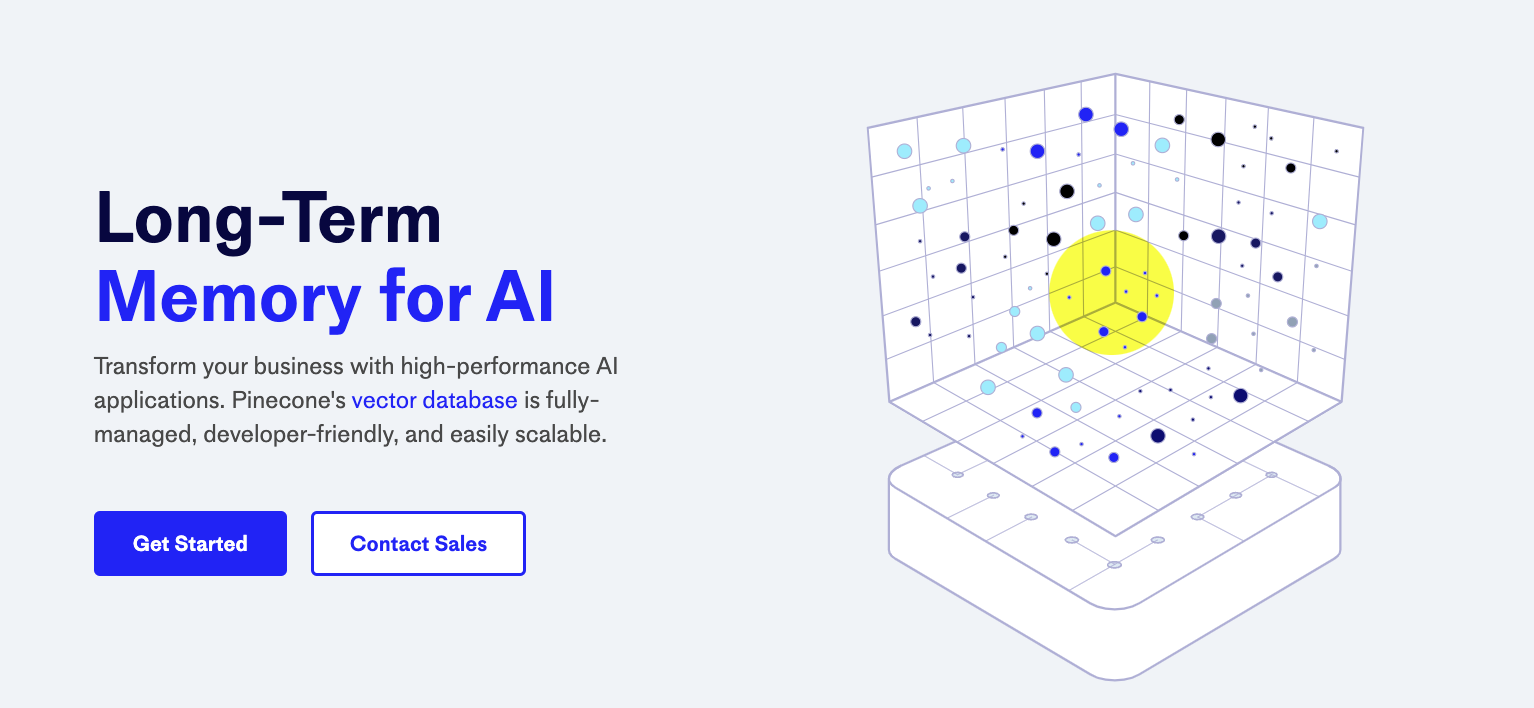

- 专用向量数据库凉了吗?

- 数据库真被卡脖子了吗?

- EL系操作系统发行版哪家强?

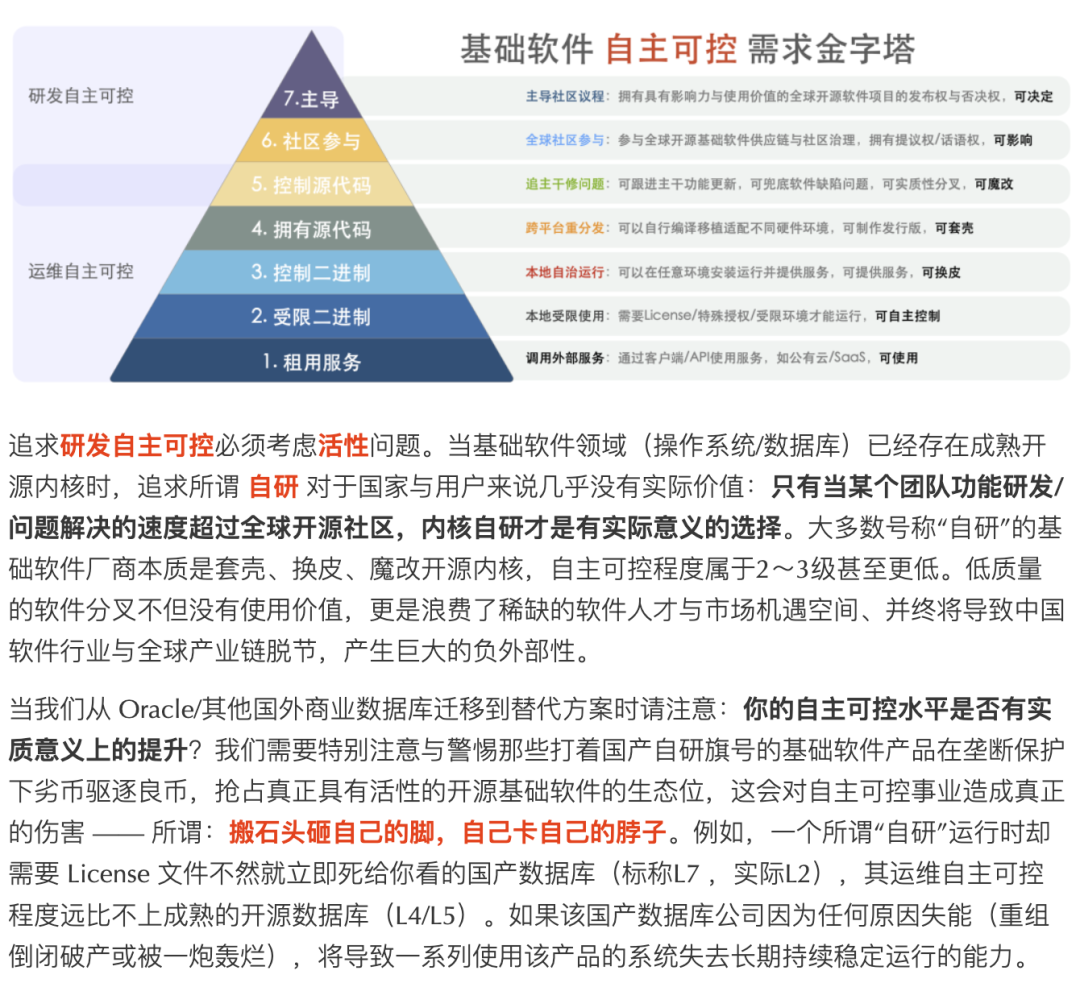

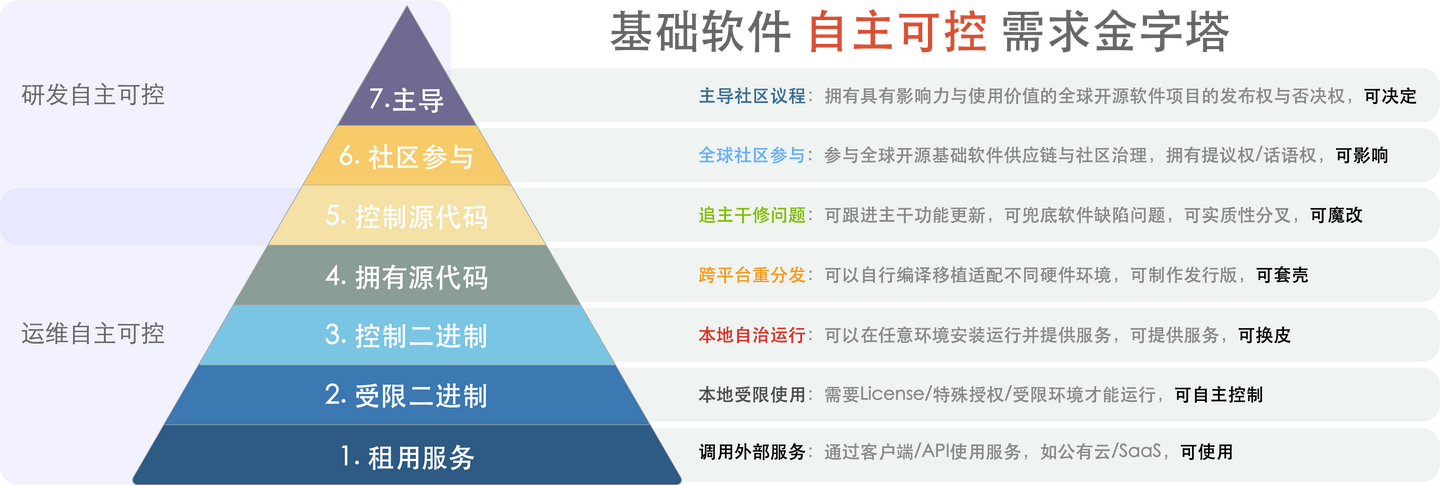

- 基础软件需要什么样的自主可控?

- 正本清源:技术反思录

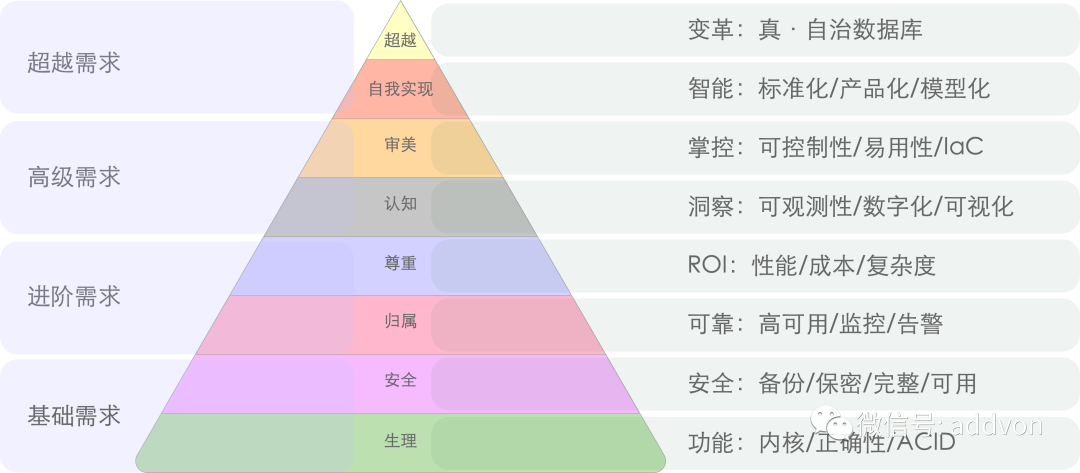

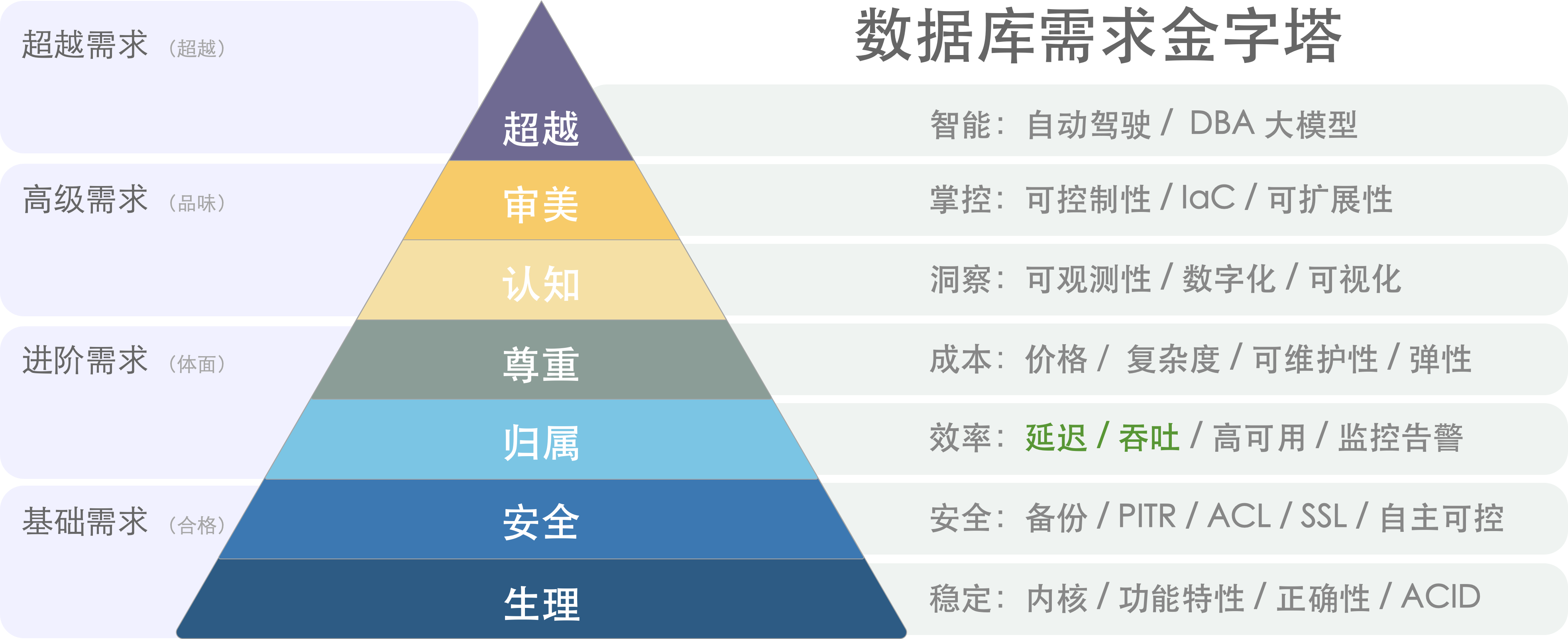

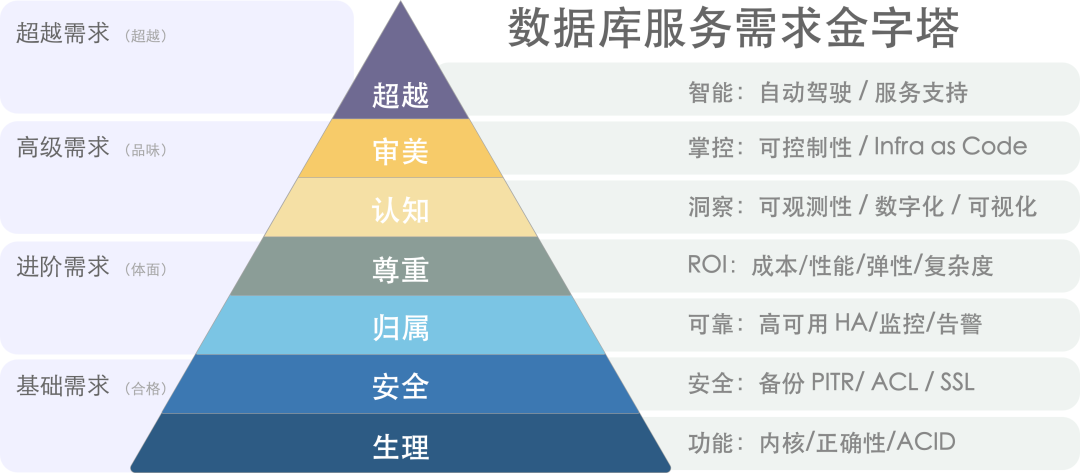

- 数据库需求层次金字塔

- 分布式数据库是不是伪需求?

- 微服务是不是个蠢主意?

- 是时候和GPL说再见了

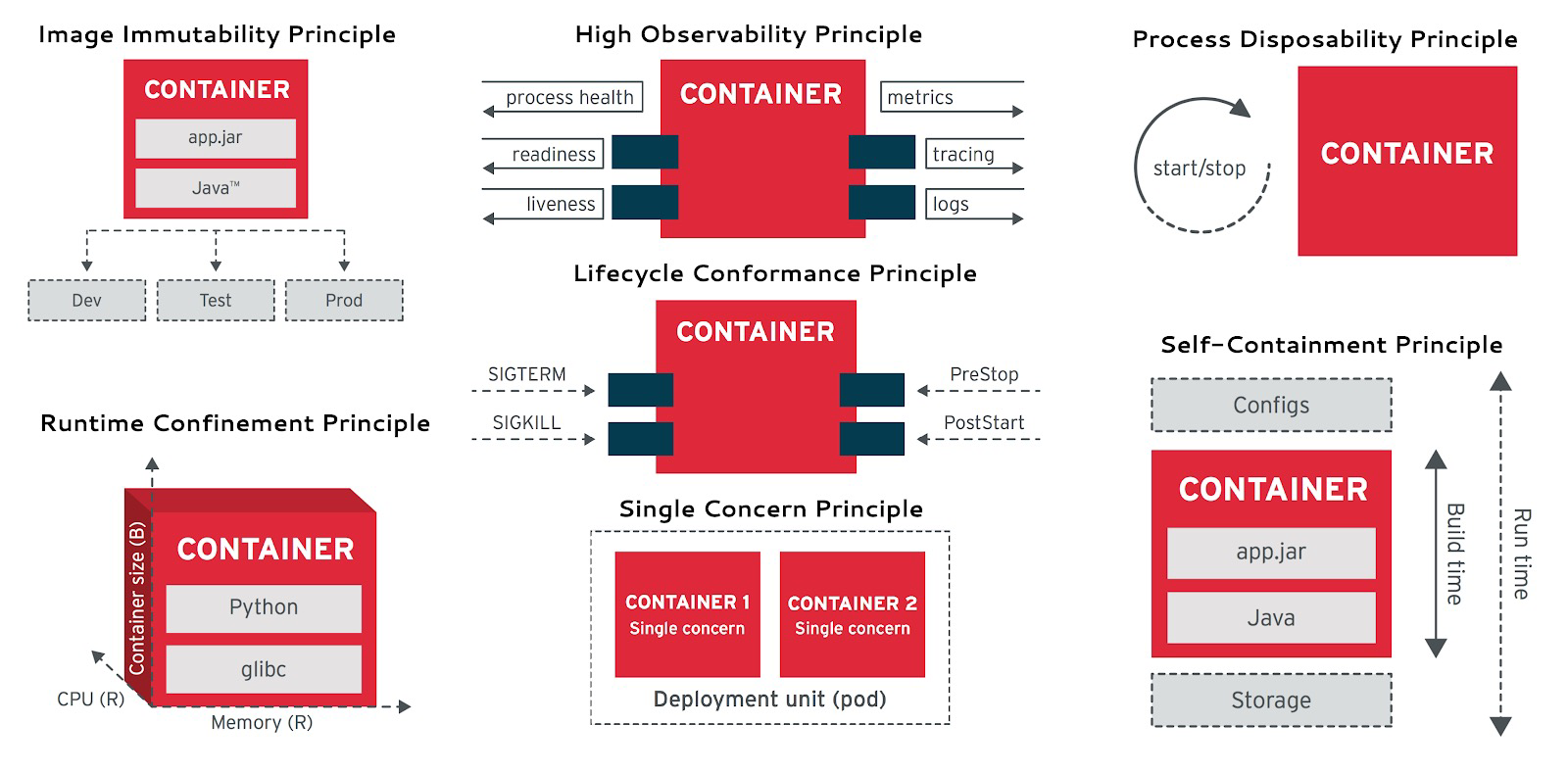

- 容器化数据库是个好主意吗?

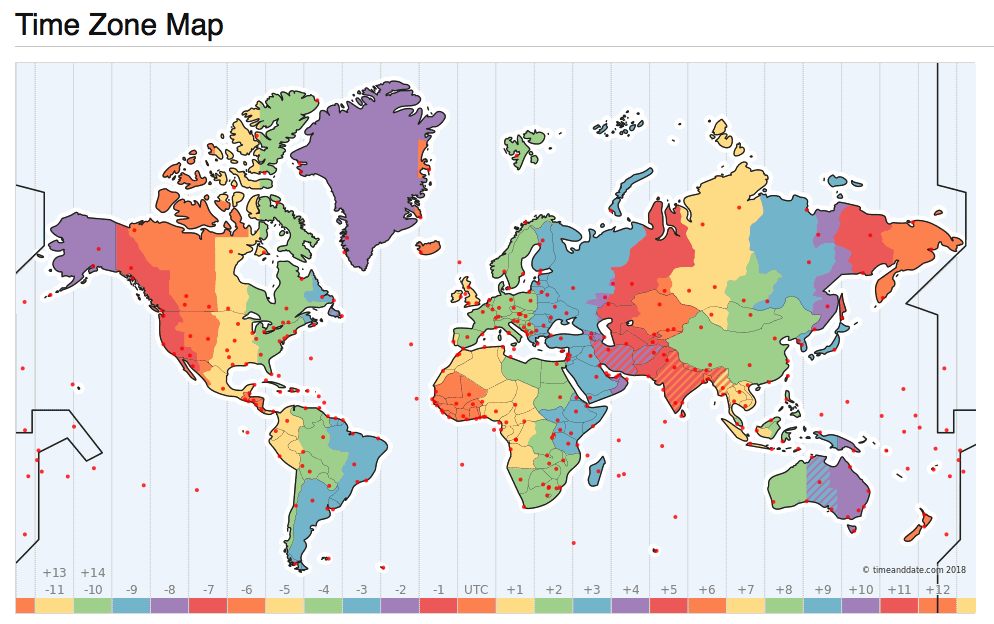

- 理解时间:闰年闰秒,时间与时区

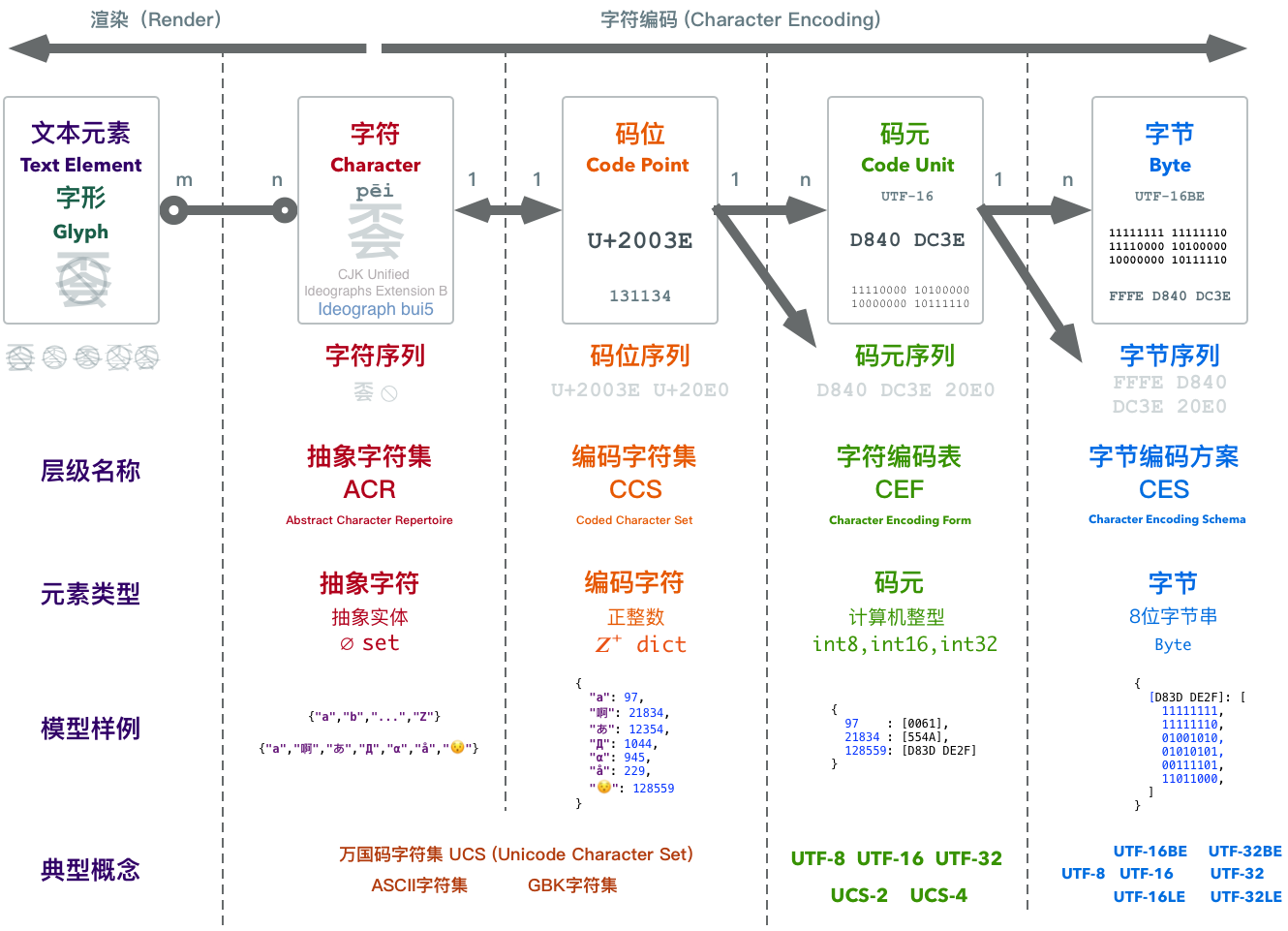

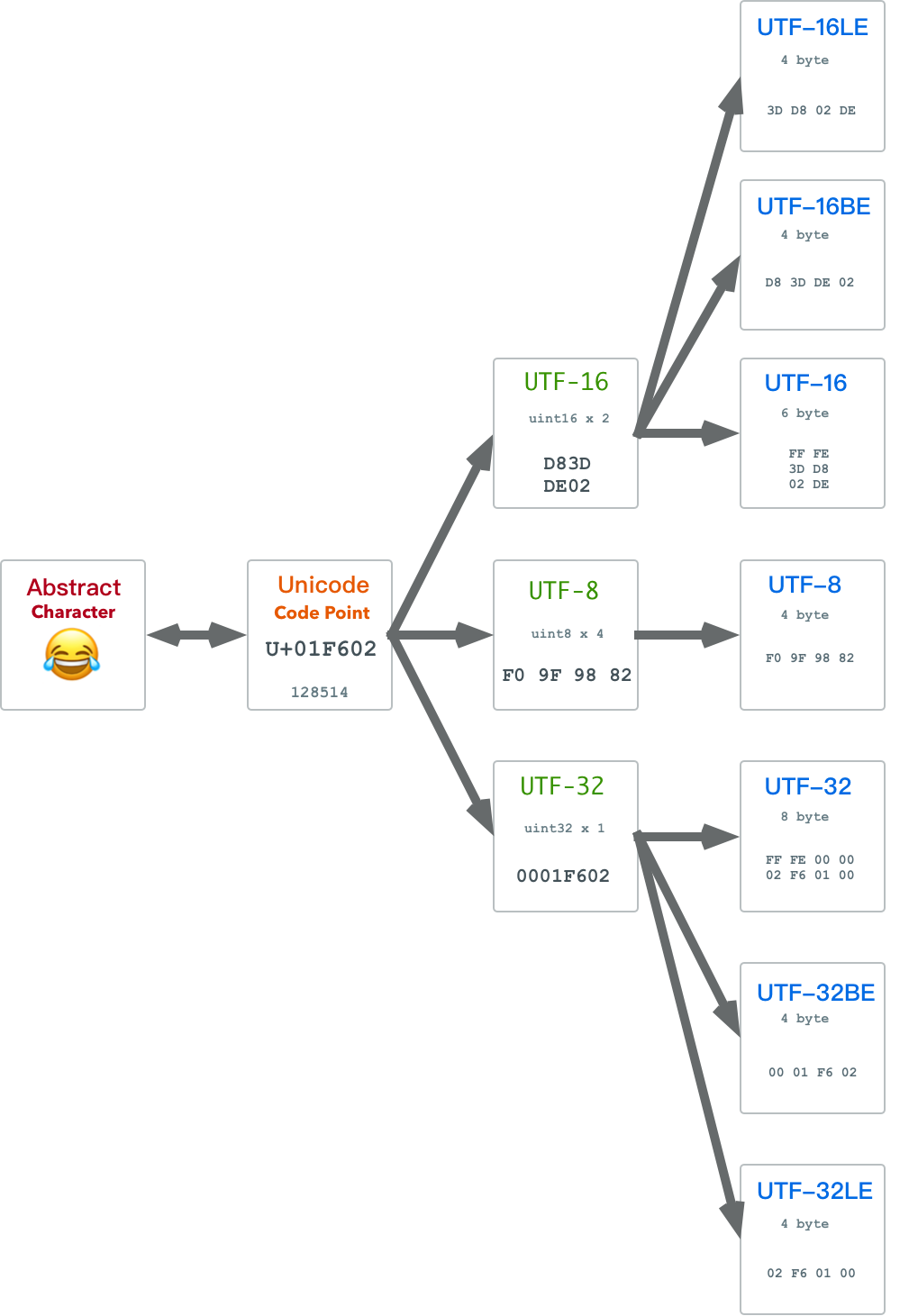

- 理解字符编码原理

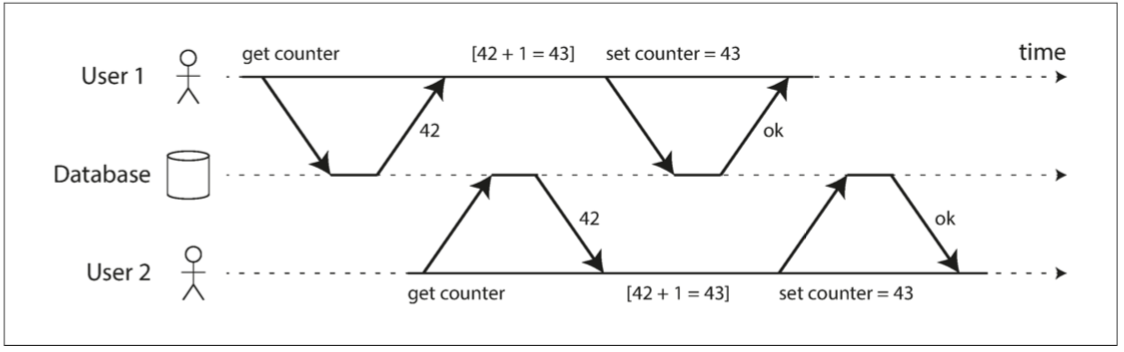

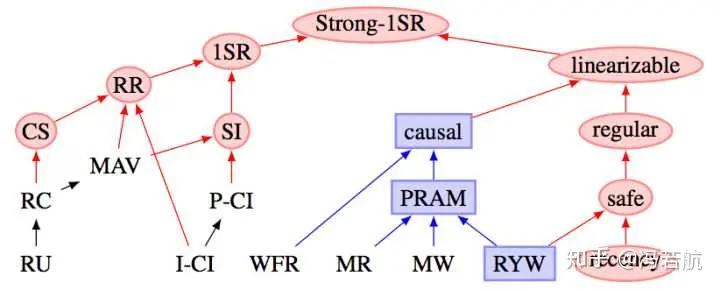

- 并发异常那些事

- 区块链与分布式数据库

- 一致性:过载的术语

- 为什么要学习数据库原理

开放数据标准:Postgres,OTel,与Iceberg

作者:Paul Copplestone,Supabase CEO 译者:冯若航,Pigsty Founder,数据库老司机

数据世界正在浮出水面的三大新标准:Postgres、Open Telemetry,以及 Iceberg。

Postgres 基本已经是事实标准;OTel 和 Iceberg 尚在成长, 但它们具备当年让 Postgres 走红的同样配方。常有人问我:“为什么最后是 Postgres 赢了?” 标准答案是“可扩展性” —— 对,但不完整。

除了产品本身优秀,Postgres 还踩中了开源生态爆点 —— 关键在于“开源的姿势”本身。

开源的三个信条

我逐渐悟到,开发者判断一个项目“开源味”浓不浓,大致看三点:

- 许可证:是否为 OSI 核准 的开源协议。

- 自托管:能否把完整产品端到端地自己部署。

- 商业化:有没有商业中立、无厂商绑架;更妙的是,有 多家 公司背书而非一家独大。

第三点我领悟得最慢 —— 是的,Postgres 赢在产品力,但更赢在 “谁也控不住” 。 治理结构与社区文化决定了它不可能被任何公司收编。它就像国际空间站,多家公司只能合作,因为谁都没本事说 “这就是我的”。

Postgres 点满了 “开源” 技能点,但它也并非在所有数据场景里都是银弹。

三类数据角色

数据领域里主要有三种 “操盘手” 及其趁手工具:

- OLTP 数据库:开发者 写应用用。

- 遥测 / 观测:SRE 运维基建、调优应用用。

- OLAP / 数仓:数据工程师 / 科学家 挖掘洞见用。

数据生命周期通常是 1 → 2 → 3:先有应用,再加点基础遥测(很多时候直接塞进 OLTP 系统),等表长到塞不下,就得上数仓了。

三类角色各玩各的,但行业正整体“左移”:工具越发友好,观测与数仓也慢慢被开发者收编。SRE 和数据岗并非故意让贤,只是数据库本身越来越能打,创业团队能撑更久再招专家。

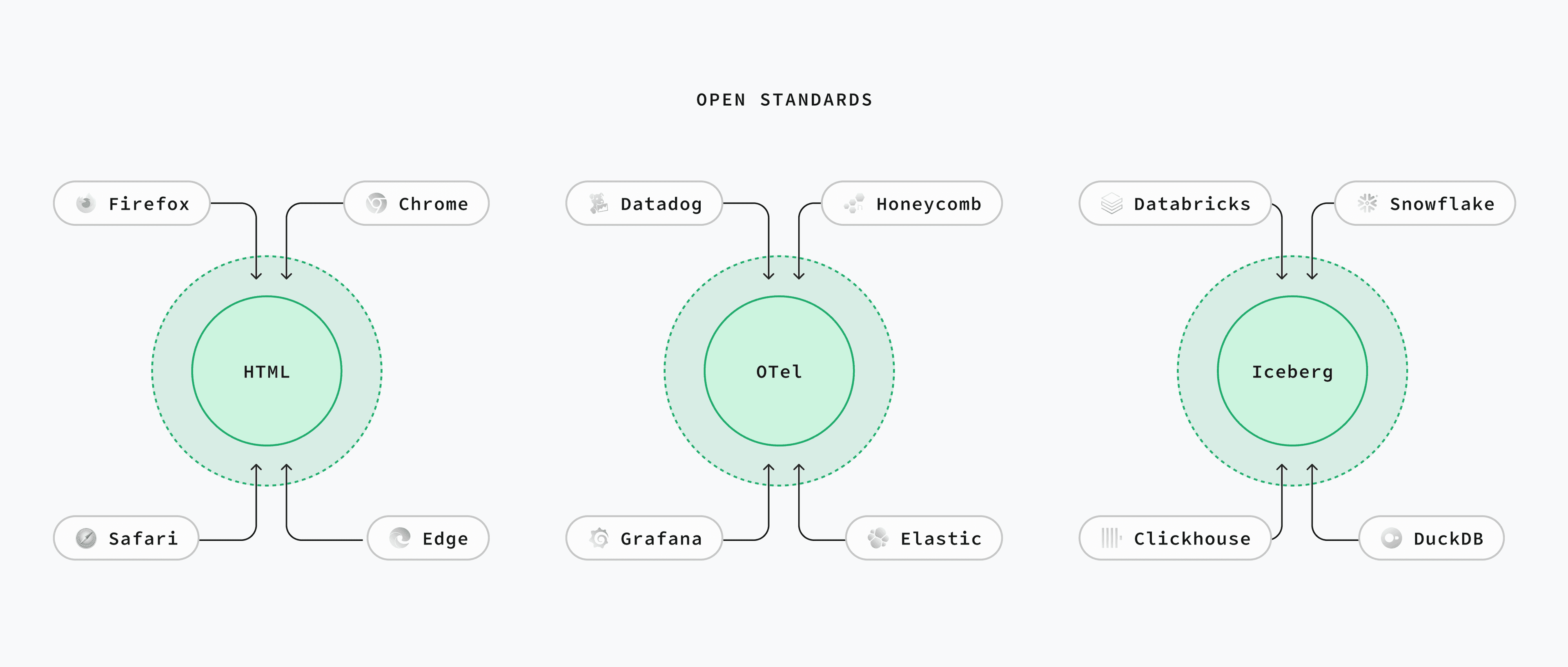

三大开放数据标准

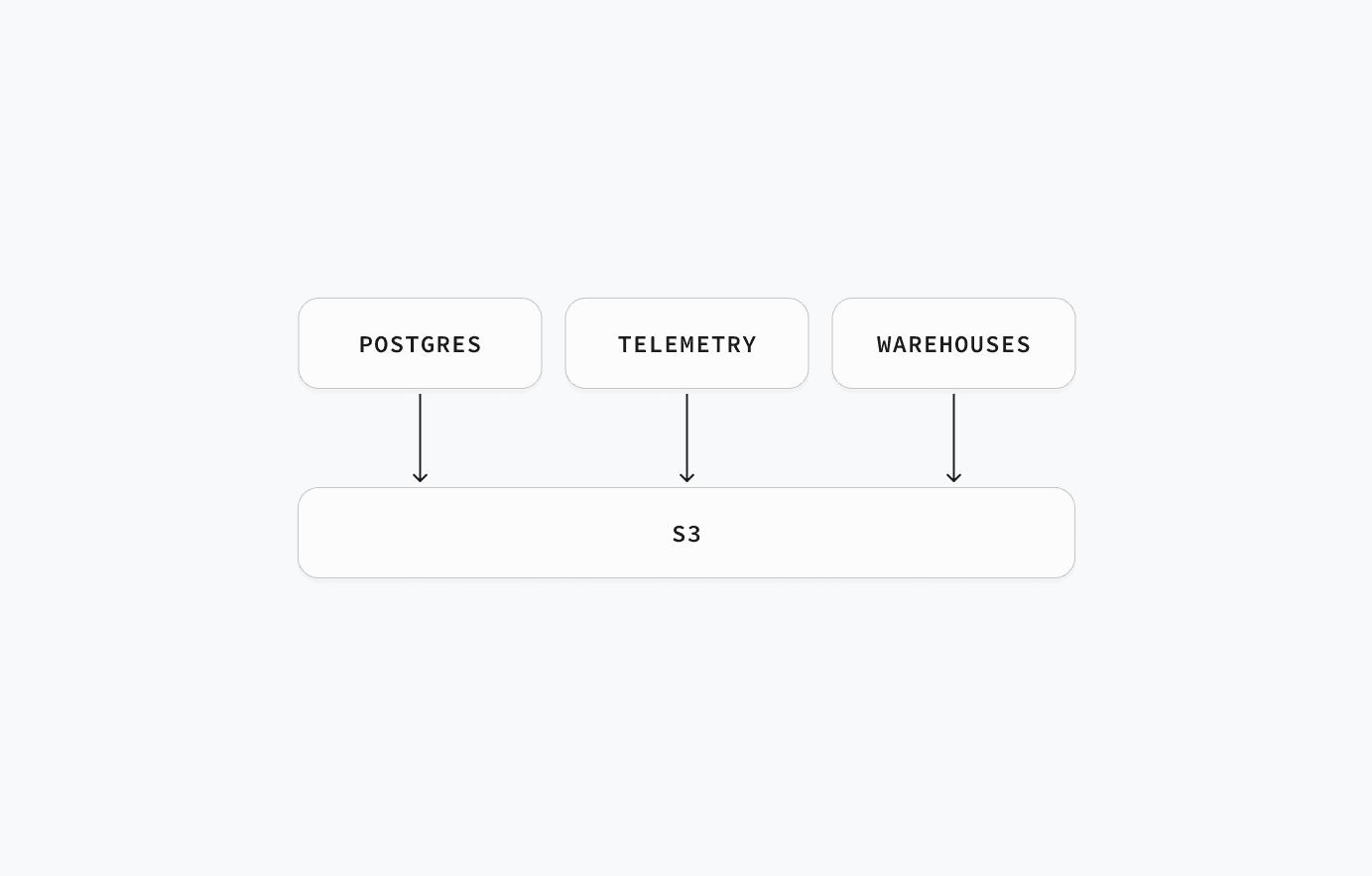

围绕以上三大场景,正冒出三套满足同样开源三信条的开放标准:

- OLTP: PostgreSQL

- 遥测: Open Telemetry

- OLAP: Iceberg

后两者更像“标准”而非“工具”,类似 HTML 与浏览器:大家约好格式,其他工具要么跟进要么淘汰。

标准往往草根起家,商业公司则陷入经典的 颠覆式创新 两难:

- 不跟?潮流跑了,错过增长趋势。

- 跟了?自家产品锁定度变低。

对开发者而言,这简直不能更香了 —— 我们坚信:可迁移性会逼着厂商拼体验。

下面逐一展开深入探讨。

Postgres:开放式 OLTP 标准

Postgres 虽是一款数据库,却已成 “标准接口”。

几乎所有新数据库都宣称“兼容 Postgres wire 协议”。

因为谁也管不了 Postgres,各大云厂商要么主动,要么被用户倒逼着上架 Postgres —— 连 Oracle Cloud 都供着。

体验差?一句 pg_dump 走人。Postgres 用 PostgreSQL License —— 功能上和 MIT 相当。

OTel:开放式遥测标准

“open telemetry” 的名字是字面含义:开放遥测。OTel 仍年轻且颇为复杂,但契合开源三信条:Apache 2.0,厂商中立。 正如云厂商拥抱 Postgres,主流观测平台也在集体投 OTel,包括 Datadog、Honeycomb、Grafana Labs 与 Elastic。 想自托管?可选 SigNoz、OpenObserve,再不济用官方 OTel 工具集。

Iceberg:开放式 OLAP 标准

开放表格式 算是新赛道:大家约定目录+元数据格式,任何计算引擎都能查询。 虽有 DeltaLake、Hudi 等对手,但目前 Iceberg 已然领跑。

各大数仓陆续“投靠” Iceberg:包括 Databricks、Snowflake 和 ClickHouse。 最关键的商业推手是 AWS —— 2024 年底官宣 S3 Tables,在 S3 上提供开箱即用的 Iceberg。

S3:终极数据基础设施

对象存储很便宜,已成三大标准的基石。今天凡是数据工具,不是原生 S3 就是兼容 S3。

AWS S3 团队连环上新,把 “S3 当数据库” 的幻想推向现实。诸如 Conditional Writes 和 S3 Express —— 速度比普通 S3 快 10 倍,最近还 逆天降价 85%。

不同场景对 S3 的姿势略有差异:

- OLTP:性能要命,S3 与 NVMe 永远隔着物理网线。因此重点是 Zero ETL & 分层存储:冷热数据自由搬迁。Postgres 现有多种读 Iceberg 的方式,如 pg_mooncake、pg_duckdb 及 Iceberg FDW。

- 遥测 / 数仓:关键字是“基数”。S3 越便宜,大家越把海量数据往里倒,催生“存算分离”的架构。于是出现一堆以计算层自居的嵌入式数据库:如 DuckDB(OLAP)、SQLite 的云后端存储、turbopuffer(向量)、SlateDB(KV)、Tonbo(Arrow)。它们既可嵌入应用,也能单飞。

Supabase 的数据蓝图

大家知道 Supabase 是 Postgres 服务商,我们花了 5 年打造让开发者舒爽的数据库平台,这仍是主航道。

不同的是,我们不止做 Postgres(虽然梗图挺火)。我们还提供 Supabase Storage,一套兼容 S3 的对象存储。未来,Supabase 聚焦的不是“一个数据库”,而是“所有数据”:

- 给我们维护的所有开源工具加上 OTel。

- 在 Supabase Storage 引入 Iceberg。

- 在 Supabase ETL 里打通 Postgres ↔ Iceberg 零 ETL。

- 通过扩展和 FDW,让 Postgres 能读能写 Iceberg。

接下来,我们押注三大开放数据标准:Postgres、OTel、Iceberg。敬请期待。

老冯点评

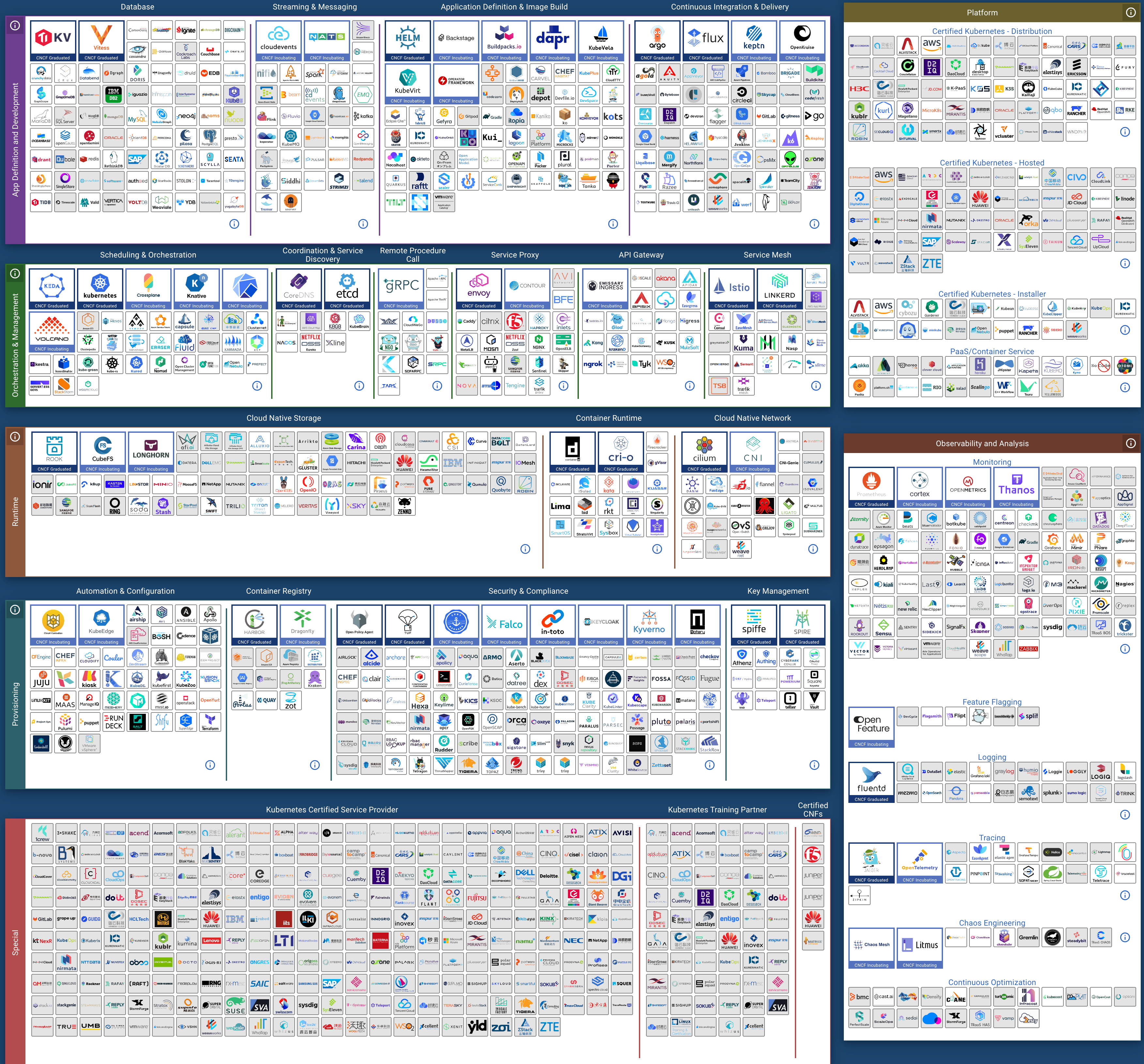

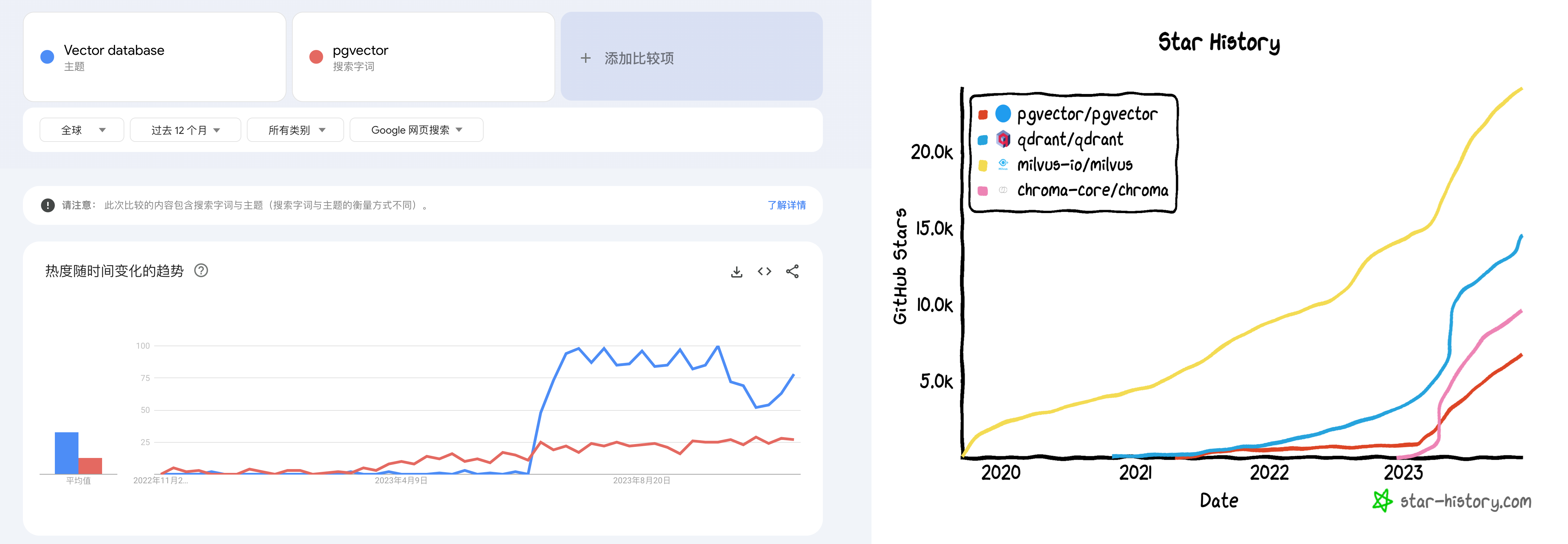

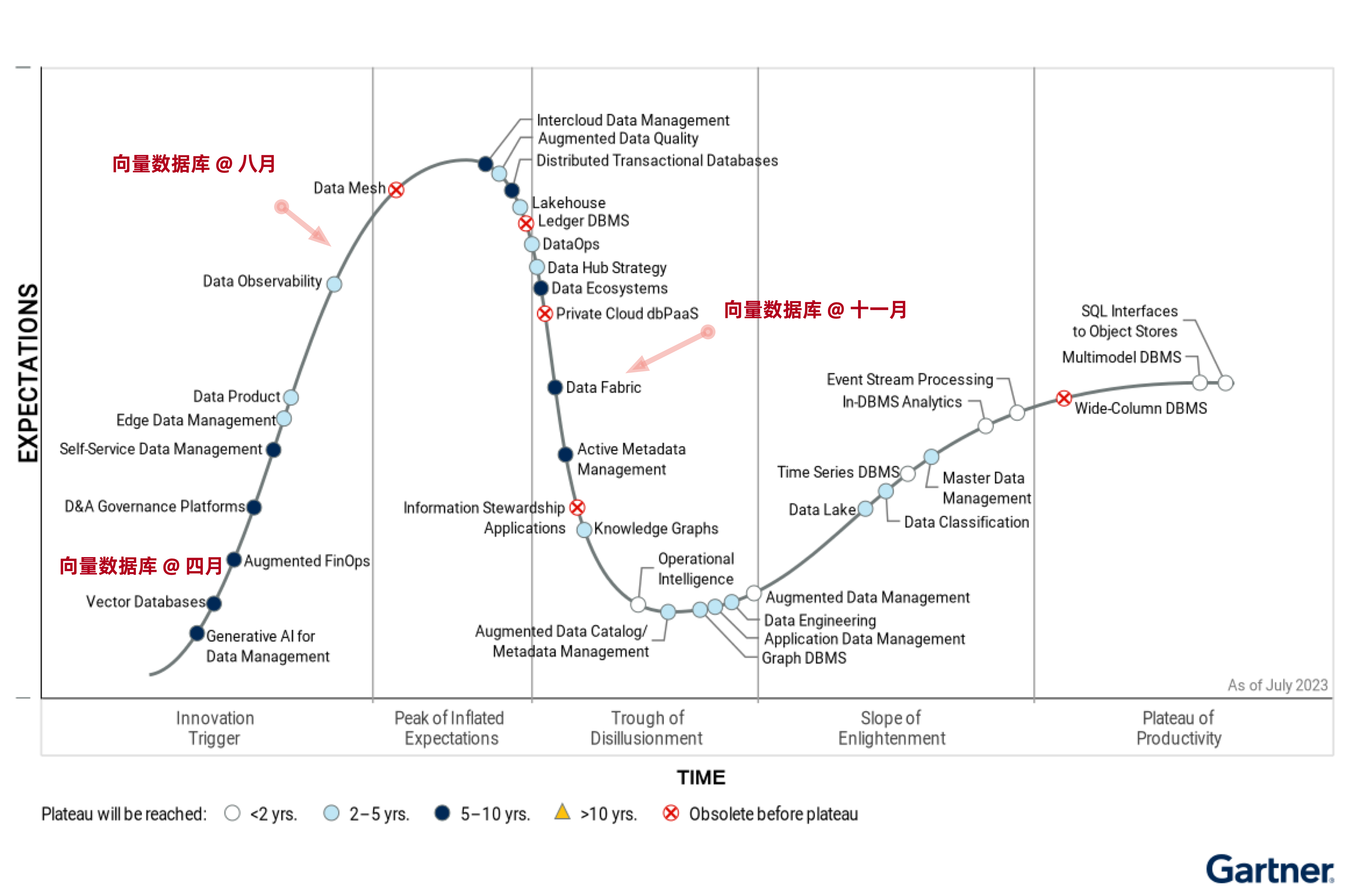

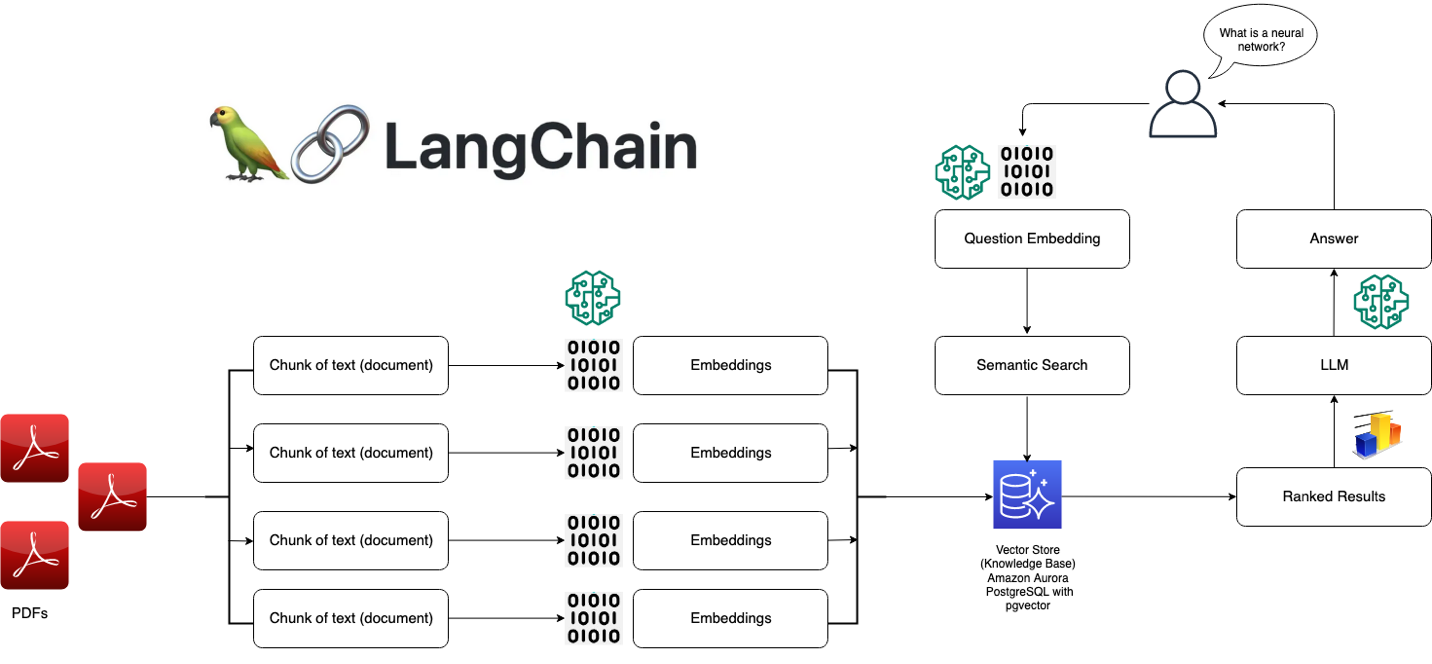

Supabase 是我最欣赏的数据库创业公司,他们的创始人认知水平非常在线。 例如在三年前 OpenAI 插件带火向量数据库赛道之前,Supabase 就已经发掘出 pgvector 进行 RAG 的玩法了。

YC S20 的项目走过五年发展到今天,已经是估值 2B 的独角兽了。目前 YC 80% 的初创公司都在用 Supabase 起步。 目前有小道消息称 OpenAI 即将收购 Supabase,如果是真的,那他们也算功德圆满,实至名归。

关于 Postgres

老冯非常认同 Paul 的观点,Postgres 已经成为 OLTP 世界的事实标准。 但至少在当下,还有几件事是 PostgreSQL “不擅长” (不是做不到)的:

- 遥测

- 海量分析

- 对象存储

所以如果你想要提供一个真正 “完全覆盖” 的数据基础设施,那么光有 PostgreSQL 是不行的。

我的意思是,你可以使用 TimescaleDB 扩展存储遥测数据,但体验与表现是比不上 Prometheus,VictoriaMetrics 的等专用 APM 组件的。 你确实可以用原生 PG,TimescaleDB,Citus,以及好几个 DuckDB 缝合扩展做数仓 —— 尽管我认为 DuckDB PG 缝合有潜力解决这个问题,但至少在当下,当数据量超过几十个 TB 时,专用数仓的性能依然还是压着 PG 打的。 有一些 “邪路” 可以将 PG 作为文件系统,例如 JuiceFS,但这仅适用于小规模的数据存储(也许几十GB?),海量 PB 级对象存储依然是原生 PG 所望尘莫及的。

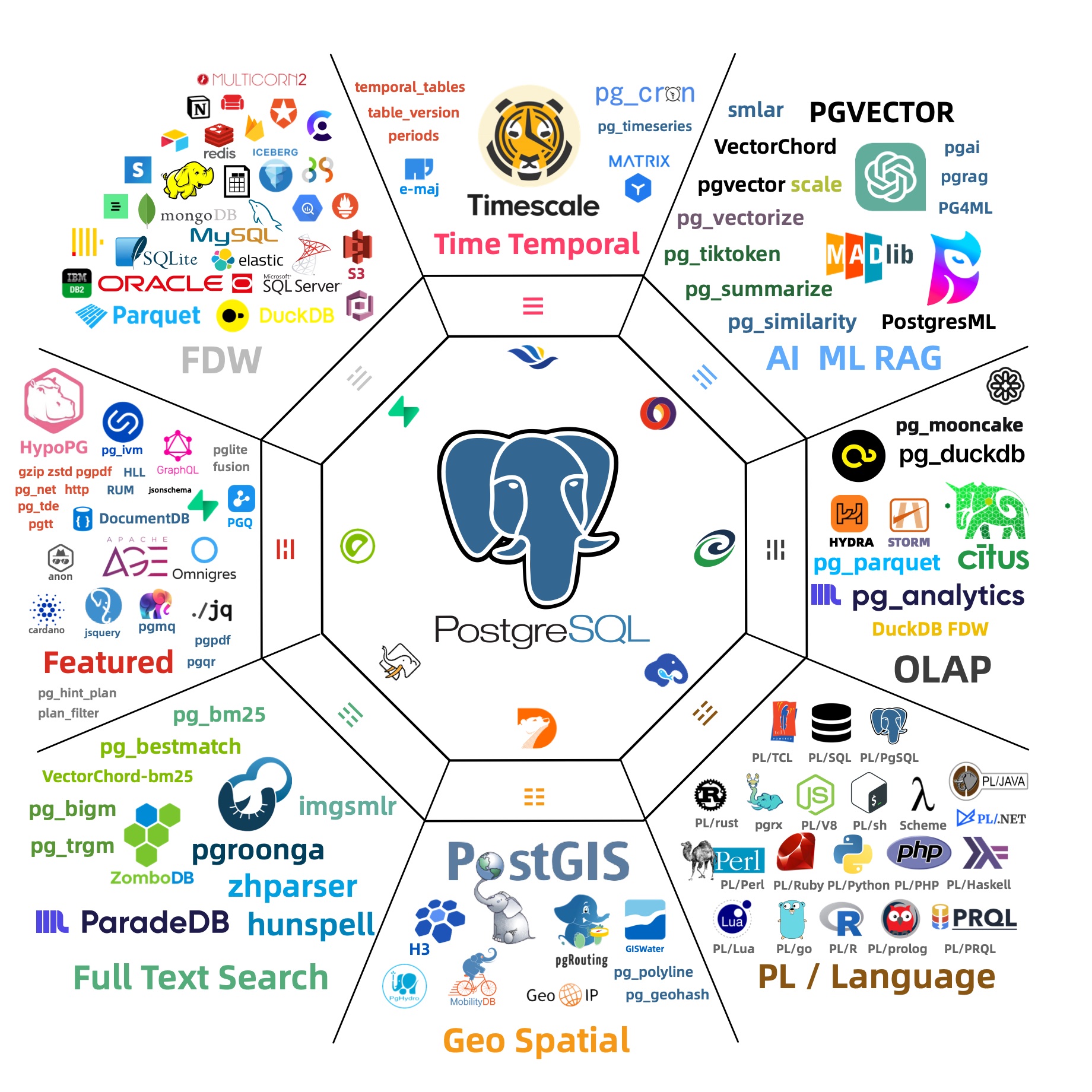

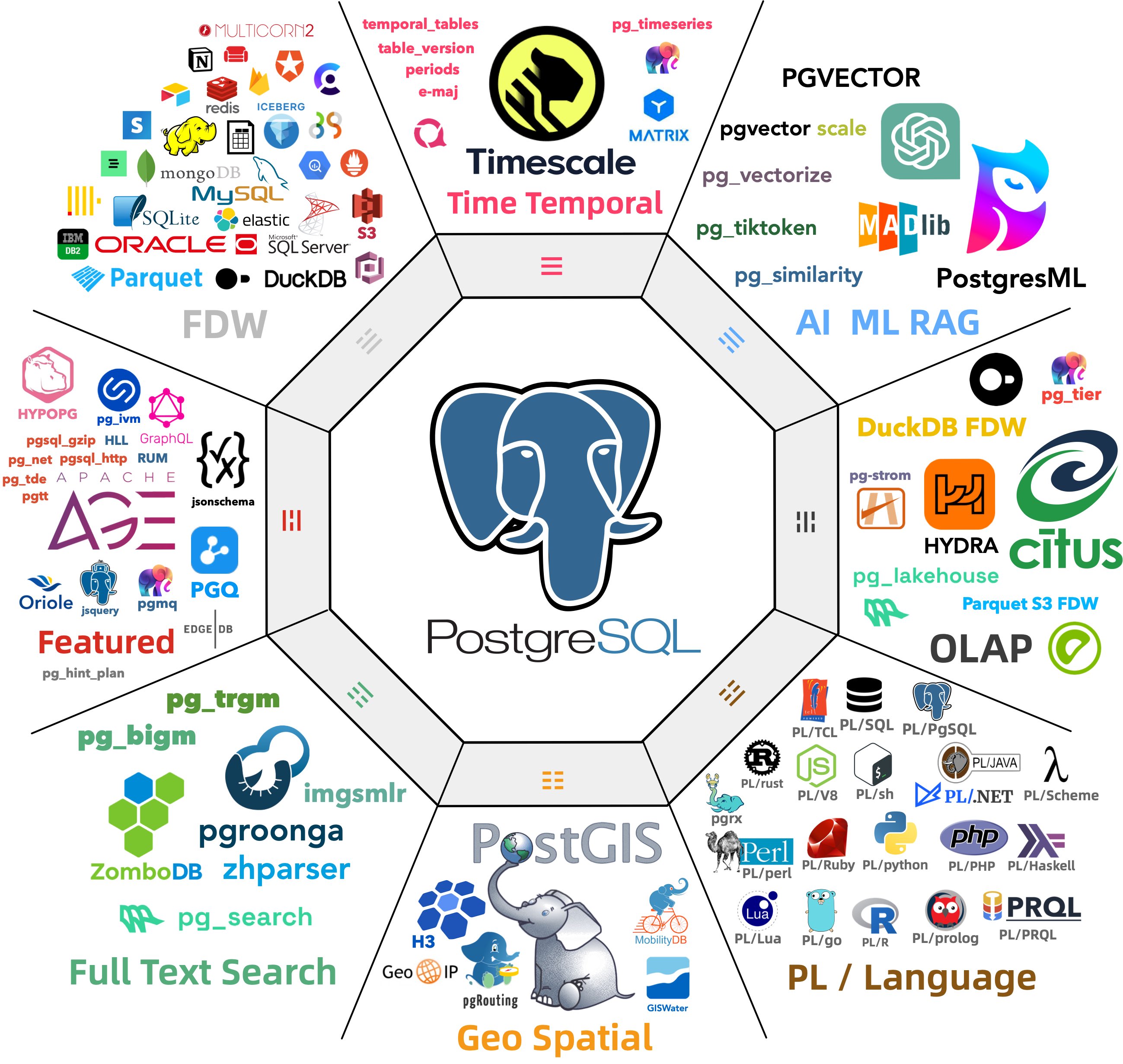

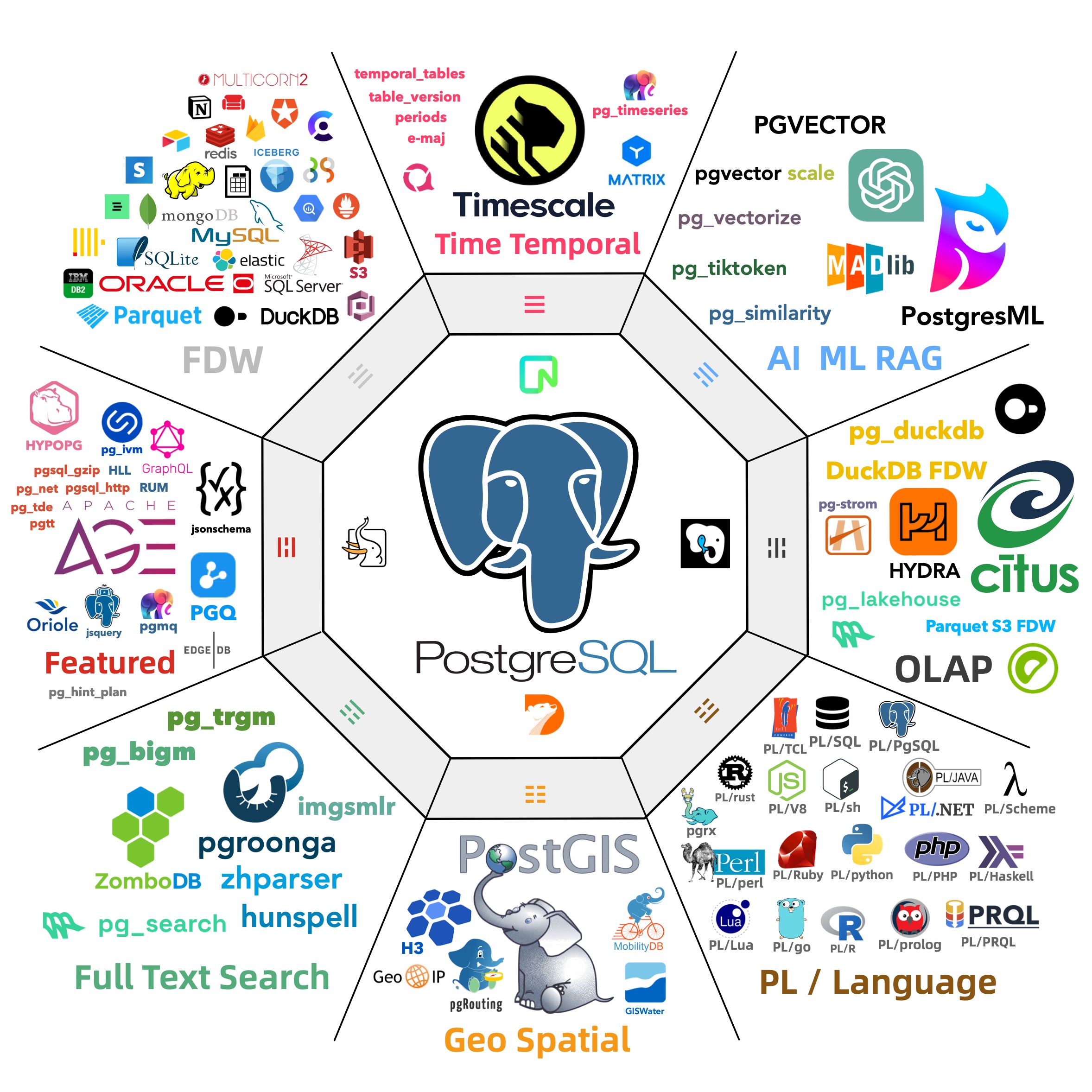

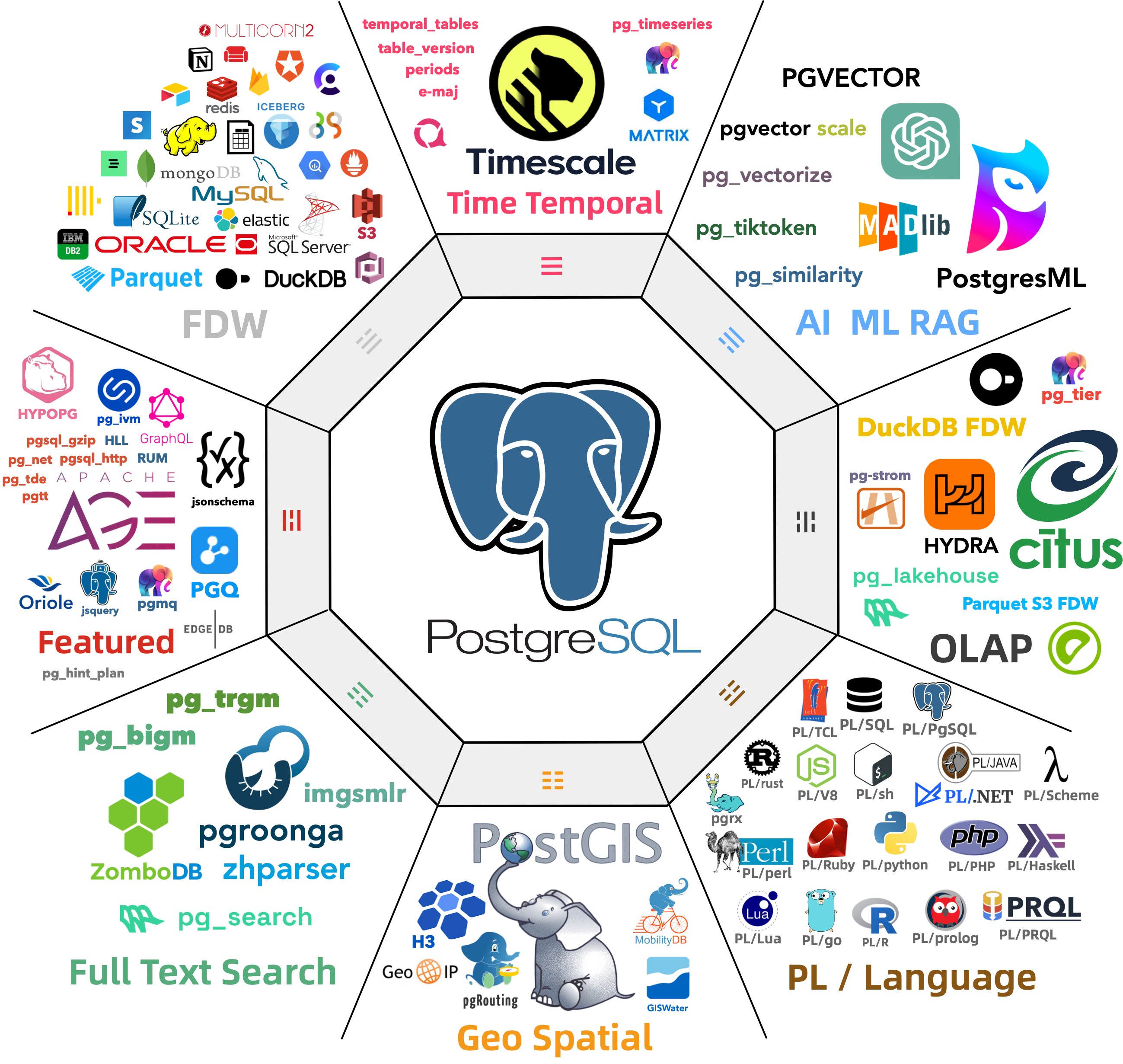

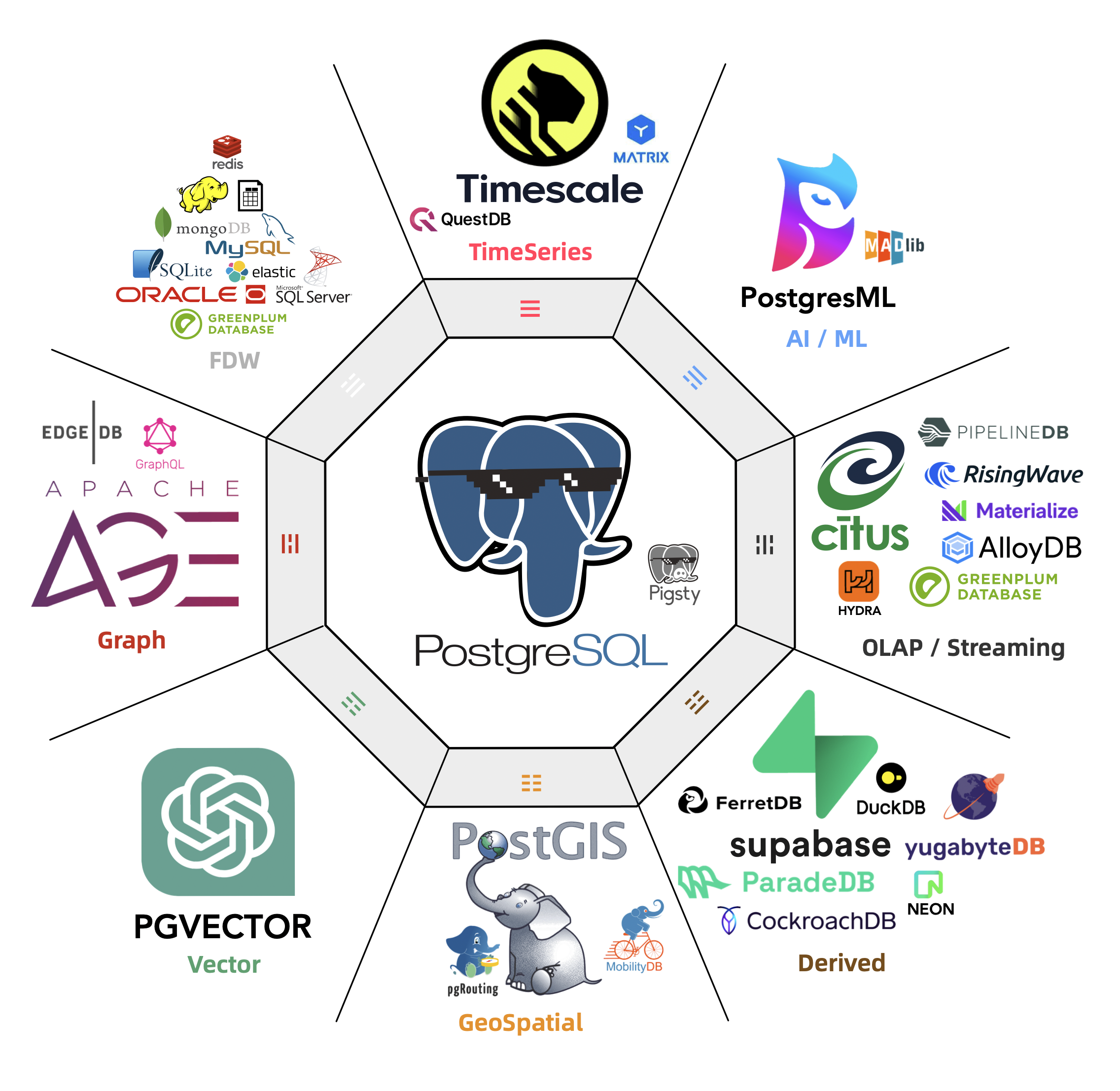

至于其他的细分领域,比如向量数据库,文档数据库,地理空间数据库,时序数据库,消息队列,全文检索引擎,乃至是图数据库,PostgreSQL 都已经 “足够好” 了。 留给其他产品的只剩下一个极端场景专用组件的 Niche,不会再有其他这种体量的玩家出现了。

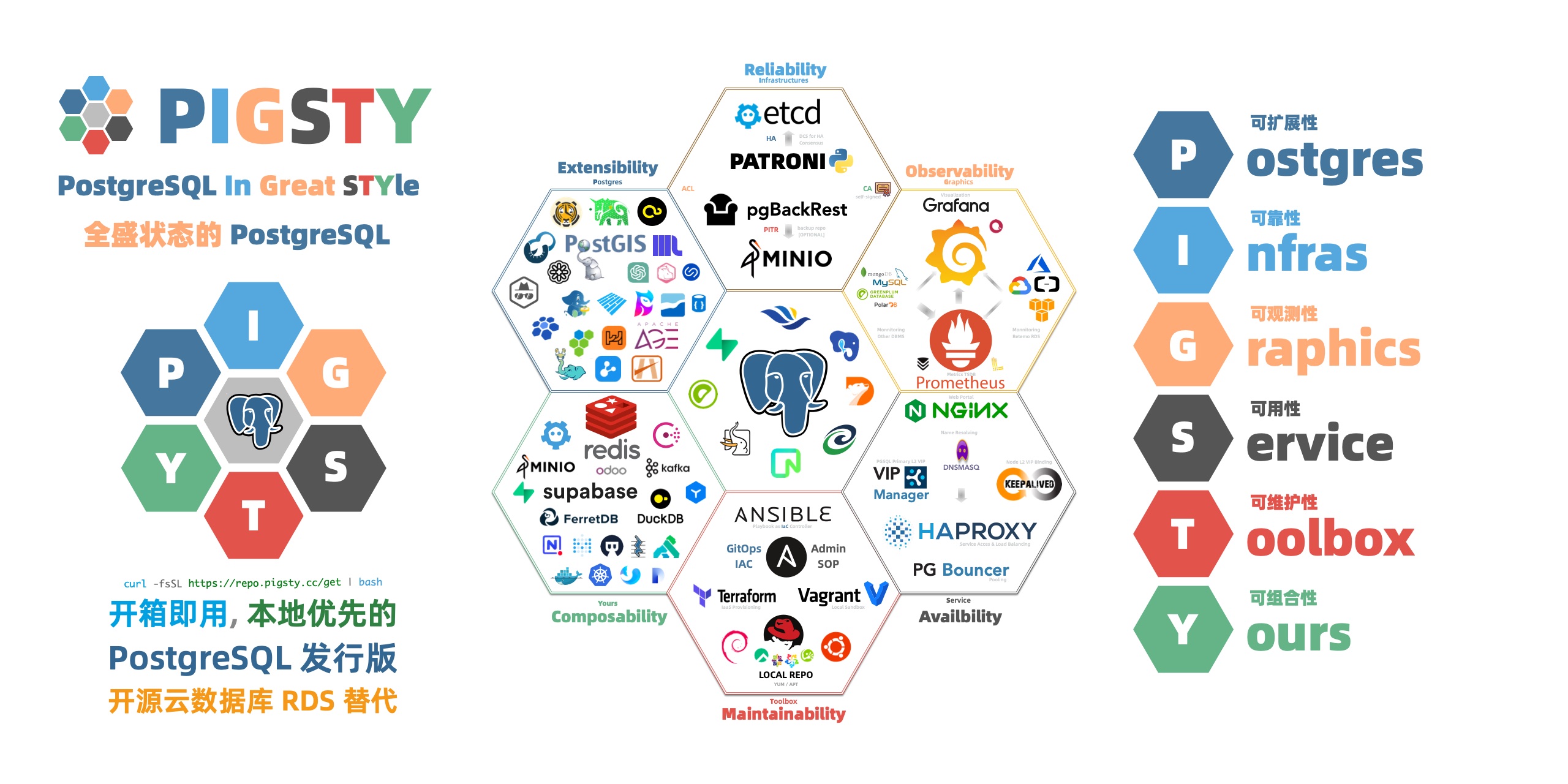

因此,在我做 Pigsty 的时候,也是用相同的思路构建的,以 PostgreSQL 为核心,以可观测性作为这个发行版的基石(Postgres in Grafana Style:这是最初的缩写),以同心圆的方式对外摊大饼。 用 MinIO 补足对象存储,用 DuckDB / Greenplum 补足数仓分析能力,最后用数量惊人的扩展插件来覆盖其他细分领域。

关于开源

Paul 说关于开源的三点精髓,第三点他领悟的是最慢的:

有没有商业中立、无厂商绑架;更妙的是,有 多家 公司背书而非一家独大。

其实我非常理解 Paul 的感受,在前两年,Supabase 的想法可能是 —— “我要占领开源道德高地,但是也要用 PG 扩展构建自己的商业壁垒。”

虽然 Supabase 提供了 Docker Compose 自建模板,但那个数据库容器镜像充其量就是个玩具,而且里面包含着隐藏的壁垒。 主要是他们自己用 Rust 写了几个扩展插件,这几个扩展插件虽然是开源的,但打包构建的知识并没有在社区普及 —— 你无法指望让用户自己去编译这些东西。

老冯就干了件 “缺德” 或者说 “有德” 的事(取决于厂家还是用户视角),把他们的扩展插件全都编译打包成了 10 大 Linux 主流系统下的 RPM/DEB 包, 这样你就可以真的在自己的 PostgreSQL 上自建 Supabase 了。我们还提供了一个模板,可以在一台裸服务器上自建 Supabase,目前是 Supabase 官方推荐的三个三方教程之一。

Supabase 还在想其他方法构建壁垒,例如他们去年收购了 OrioleDB,一个云原生,无膨胀的 PostgreSQL 存储引擎扩展(需要Patch内核)。 还没等正式 GA 上线,老冯就也已经打好了 OrioleDB 的 RPM/DEB 包,供用户自建使用了。

我估计 Paul 的心情是复杂的,一方面他想要将用户锁定在 Supabase 云服务上,看到别人真的用开源来拆台,心里肯定不爽。 但另一方面正是这些三方社区厂商的努力,反而让 Supabase 开枝散叶,不是一个 “只有我提供” 的东西,有了开源的醍醐味。 所以最后也释然了,坦然接受了这种现状。

但这件事也对老冯有所触动,我也开始思考,Pigsty 作为一个开源项目,是否也有类似的 “开源三信条”?

老实说,老冯很怀念全职创业前的那种状态,完全不考虑商业化,为了兴趣,热情,公益而开源,所以使用的是 Apache 2.0 协议。 后来因为拿投资人钱要有一个交代,所以把协议修改为更严格的 AGPLv3 ,目标是为了阻止云厂商与同行白嫖。 但既然现在我又成了数据库个体户,其实也是可以回到 Supabase 的这种状态 —— 用就用吧,反正我也不指望靠这个赚钱。

数据库老司机:文章导航

国产信创篇

- 2025-02-28 国产数据库里有能打的吗?

- 2024-11-18 这么吹国产数据库,听的尴尬癌都要犯了

- 2024-10-25 开源皇帝Linus清洗整风

- 2024-10-01 第二批数据库国测名单:国产化来了怎么办?

- 2024-07-15 机场出租车恶性循环与国产数据库怪圈

- 2024-04-25 国产数据库到底能不能打?

- 2024-01-11 国产数据库是大炼钢铁吗?

- 2024-01-08 中国对PostgreSQL的贡献约等于零吗?

- 2023-11-02 数据库真被卡脖子了吗?

- 2023-10-09 EL系操作系统发行版哪家强?

- 2023-08-31 基础软件到底需要什么样的自主可控?

行业洞察篇

- 2025-05-27 开放数据标准:Postgres,OTel,与Iceberg Paul

- 2025-05-23 小数据的失落十年:分布式分析的错付

- 2025-04-27 SaaS已死?AI时代,软件从数据库开始

- 2025-04-28 分布式数据库是伪需求

- 2025-04-14 Claude Code泄密:MCP 爆火的隐藏真相

- 2025-03-13 数据库火星撞地球:当PG爱上DuckDB

- 2025-03-10 HTAP数据库,一场无人鼓掌的演出

- 2024-12-03 七周七数据库 @ 2025

- 2024-11-21 面向未来数据库的现代硬件

- 2024-11-17 20刀好兄弟PolarDB:论数据库该卖什么价?

- 2024-08-13 谁整合好DuckDB,谁赢得OLAP数据库世界

- 2023-11-22 向量数据库凉了吗?

- 2023-11-17 重新拿回计算机硬件的红利

- 2023-04-17 分布式数据库是伪需求吗?

- 2023-03-29 数据库需求层次金字塔

DBA/RDS篇

- 2025-05-18 不缺好数据库内核,缺能用好数据库的DBA

- 2025-05-09 这次数据库真爆炸了,但摇人也没用了

- 2025-04-28 数据库爆炸了怎么摇人?

- 2024-09-07 先优化碳基BIO核,再优化硅基CPU核

- 2023-12-05 数据库应该放入K8S里吗?

- 2023-12-04 把数据库放入Docker是一个好主意吗?

- 2023-01-30 云数据库是不是智商税

- 2022-05-16 云RDS:从删库到跑路

- 2024-02-02 DBA会被云淘汰吗?

- 2023-03-01 驳《再论为什么你不应该招DBA》

- 2023-01-31 你怎么还在招聘DBA? 马工

- 2022-05-10 DBA还是一份好工作吗?

PG生态篇

- 2025-05-16 PGCon.dev闪电演讲,硬控PG大佬5分钟

- 2025-04-09 PG扩展峰会日程出炉,蒙特利尔见

- 2025-04-06 OrioleDB 奥利奥数据库来了!

- 2025-04-03 带有MySQL兼容的PG内核现已加入Pigsty

- 2025-03-01 PostgreSQL取得对MySQL的压倒性优势

- 2025-01-01 Andy Pavlo: 2024年度数据库回顾

- 2024-12-18 PostgreSQL 2024 社区现状调查报告

- 2024-07-25 StackOverflow 2024调研:PostgreSQL已经超神了

- 2024-03-24 PostgreSQL会修改开源许可证吗?

- 2024-05-16 为什么PostgreSQL是未来数据的基石?

- 2024-03-16 PostgreSQL is eating the database world

- 2024-03-04 PostgreSQL正在吞噬数据库世界

- 2024-02-19 技术极简主义:一切皆用Postgres

- 2024-01-03 2023年度数据库:PostgreSQL (DB-Engine)

- 2022-08-22 PostgreSQL 到底有多强?

- 2022-07-12 为什么PostgreSQL是最成功的数据库?

- 2022-06-24 StackOverflow 2022数据库年度调查

- 2021-05-08 为什么说PostgreSQL前途无量?

最佳实践篇

- 2025-05-19 OpenAI:将PostgreSQL伸缩至新阶段

- 2025-05-03 影视飓风达芬奇千万级数据库演化及实践

- 2025-03-21 PGFS:将数据库作为文件系统

- 2024-11-30 你为什么不用连接池?

- 2024-01-13 令人惊叹的PostgreSQL可伸缩性

PG发布篇

- 2024-11-15 不要更新!发布当日叫停:PG也躲不过大翻车

- 2024-11-14 PostgreSQL 12 过保,PG 17 上位

- 2024-11-02 PostgreSQL神功大成!最全扩展仓库

- 2024-09-27 PostgreSQL 17 发布:摊牌了,我不装了!

- 2024-09-05 PostgreSQL 17 RC1 发布!与近期PG新闻

- 2024-08-09 PostgreSQL小版本更新,17beta3,12将EOL

- 2024-05-24 PostgreSQL 17 Beta1 发布!牙膏管挤爆了!

- 2024-01-14 快速掌握PostgreSQL版本新特性

- 2024-01-05 展望PostgreSQL的2024 (Jonathan Katz)

创业融资篇

- 2025-05-12 数据库茶水间:OpenAI拟收购Supabase ?

- 2025-05-06 PG生态赢得资本市场青睐:Databricks收购Neon,Supabase融资两亿美元,微软财报点名PG

- 2024-09-26 PG系创业公司Supabase:$80M C轮融资

- 2024-07-31 ClickHouse收购PeerDB:这浓眉大眼的也要来搞 PG 了?

- 2024-02-18 PG生态新玩家ParadeDB

- 2023-10-08 FerretDB:假扮成MongoDB的PostgreSQL?

MySQL杀手篇

- 2024-11-05 PZ:MySQL还有机会赶上PostgreSQL的势头吗?

- 2024-07-12 MySQL新版恶性Bug,表太多就崩给你看!

- 2024-07-09 MySQL安魂九霄,PostgreSQL驶向云外

- 2024-06-26 用PG的开发者,年薪比MySQL多赚四成?

- 2024-06-20 Oracle最终还是杀死了MySQL!

- 2024-06-19 MySQL性能越来越差,Sakila将何去何从?

- 2023-12-30 MySQL的正确性为何如此拉垮?

- 2023-08-11 如何看待 MySQL vs PGSQL 直播闹剧

- 2023-08-09 驳《MySQL:这个星球最成功的数据库》

其他DB篇

- 2024-09-04 MongoDB没有未来:“好营销”救不了烂芒果

- 2024-09-03 《黑历史:Mongo》:现由PostgreSQL驱动

- 2024-09-02 PostgreSQL可以替换微软SQL Server吗?

- 2024-08-30 ElasticSearch又重新开源了???

- 2024-03-26 Redis不开源是“开源”之耻,更是公有云之耻

- 2023-10-08 FerretDB:假扮成MongoDB的PostgreSQL?

司机本人篇

- 2024-08-22 GOTC 2024 BTW采访冯若航:Pigsty作者,简化PG管理,推动PG开源社区的中国参与

- 2023-12-31 2023总结:三十而立

- 2023-09-08 冯若航:不想当段子手的技术狂,不是一位好的开源创始人

- 2022-07-07 90后,辞职创业,说要卷死云数据库

数据库老司机专栏

- 2025-05-27 开放数据标准:Postgres,OTel,与Iceberg

- 2025-05-23 小数据的失落十年:分布式分析的错付

- 2025-05-19 OpenAI:将PostgreSQL伸缩至新阶段

- 2025-05-18 不缺好数据库内核,缺能用好数据库的DBA

- 2025-05-16 PGCon.dev闪电演讲,硬控PG大佬5分钟

- 2025-05-12 数据库茶水间:OpenAI拟收购Supabase ?

- 2025-05-09 这次数据库真爆炸了,但摇人也没用了

- 2025-04-28 数据库爆炸了怎么摇人?

- 2025-05-06 PG生态赢得资本市场青睐:Databricks收购Neon,Supabase融资两亿美元,微软财报点名PG

- 2025-05-03 影视飓风达芬奇千万级数据库演化及实践

- 2025-04-27 SaaS已死?AI时代,软件从数据库开始

- 2025-04-28 分布式数据库是伪需求

- 2025-04-19 兼容Oracle的开源 PostgreSQL?

- 2025-04-17 2025年:MySQL vs PostgreSQL

- 2025-04-16 PG被黑慢MySQL 360倍,这次我真忍不了

- 2025-04-14 Claude Code泄密:MCP 爆火的隐藏真相

- 2025-04-09 PG扩展峰会日程出炉,蒙特利尔见

- 2025-04-06 OrioleDB 奥利奥数据库来了!

- 2025-04-03 带有MySQL兼容的PG内核现已加入Pigsty

- 2025-03-21 PGFS:将数据库作为文件系统

- 2025-03-13 数据库火星撞地球:当PG爱上DuckDB

- 2025-03-10 HTAP数据库,一场无人鼓掌的演出

- 2025-03-06 阿里云rds_duckdb:致敬还是抄袭?

- 2025-03-01 PostgreSQL取得对MySQL的压倒性优势

- 2025-02-28 国产数据库里有能打的吗?

- 2025-02-27 对比Oracle与PostgreSQL事务系统

- 2025-02-11 如何在数据库中直接检索PDF

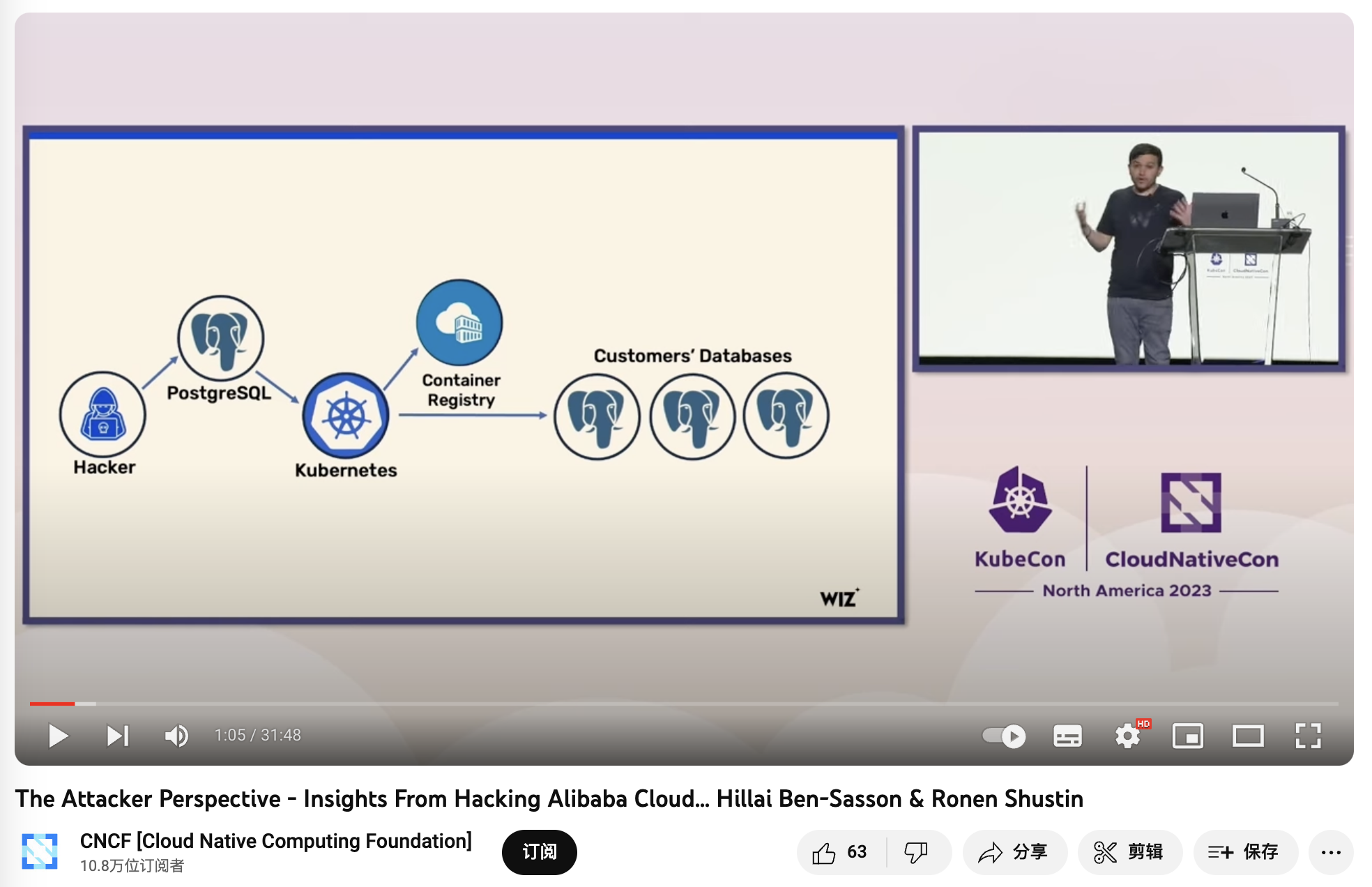

- 2025-03-12 Wiz: DeepSeek数据库暴露

- 2025-01-24 PostgreSQL 生态前沿进展

- 2025-01-22 数据库即架构

- 2025-01-16 网传江西教育厅高考查分网站删库跑路

- 2025-01-14 PostgreSQL荣获2024年度数据库(5冠王)

- 2025-01-11 PII数据安全合规与PG Anonymizer最佳实践

- 2025-01-07 第七届PG生态大会:一些感想

- 2025-01-01 Andy Pavlo: 2024年度数据库回顾

- 2024-12-31 Pigsty@2024:今年没啥财运,但事儿整的还不赖

- 2024-12-23 小猪骑大象:PG内核与扩展包管理神器

- 2024-12-18 PostgreSQL 2024 社区现状调查报告

- 2024-12-03 七周七数据库 @ 2025

- 2024-11-30 你为什么不用连接池?

- 2024-11-26 创业出海神器 Supabase 自建指南

- 2024-11-21 面向未来数据库的现代硬件

- 2024-11-18 这么吹国产数据库,听的尴尬癌都要犯了

- 2024-11-17 20刀好兄弟PolarDB:论数据库该卖什么价?

- 2024-11-15 不要更新!发布当日叫停:PG也躲不过大翻车

- 2024-11-14 PostgreSQL 12 过保,PG 17 上位

- 2024-11-05 PZ:MySQL还有机会赶上PostgreSQL的势头吗?

- 2024-11-02 PostgreSQL神功大成!最全扩展仓库

- 2024-10-28 YC教父Paul Graham:写作者与非写作者

- 2024-10-25 开源皇帝Linus清洗整风

- 2024-10-01 第二批数据库国测名单:国产化来了怎么办?

- 2024-09-27 PostgreSQL 17 发布:摊牌了,我不装了!

- 2024-09-26 PG系创业公司Supabase:$80M C轮融资

- 2024-09-07 先优化碳基BIO核,再优化硅基CPU核

- 2024-09-05 PostgreSQL 17 RC1 发布!与近期PG新闻

- 2024-09-04 MongoDB没有未来:“好营销”救不了烂芒果

- 2024-09-03 《黑历史:Mongo》:现由PostgreSQL驱动

- 2024-09-02 PostgreSQL可以替换微软SQL Server吗?

- 2024-08-30 ElasticSearch又重新开源了???

- 2024-08-22 GOTC 2024 BTW采访冯若航:Pigsty作者,简化PG管理,推动PG开源社区的中国参与

- 2024-08-13 谁整合好DuckDB,谁赢得OLAP数据库世界

- 2024-08-09 PostgreSQL小版本更新,17beta3,12将EOL

- 2024-08-06 PG隆中对,一个PG三个核,一个好汉三百个帮

- 2024-08-03 最近在憋大招,数据库全能王真的要来了

- 2024-07-31 ClickHouse收购PeerDB:这浓眉大眼的也要来搞 PG 了?

- 2024-07-25 StackOverflow 2024调研:PostgreSQL已经超神了

- 2024-07-15 机场出租车恶性循环与国产数据库怪圈

- 2024-07-12 MySQL新版恶性Bug,表太多就崩给你看!

- 2024-07-09 MySQL安魂九霄,PostgreSQL驶向云外

- 2024-06-28 CentOS 7过保了,换什么OS发行版更好?

- 2024-06-26 用PG的开发者,年薪比MySQL多赚四成?

- 2024-06-20 Oracle最终还是杀死了MySQL!

- 2024-06-19 MySQL性能越来越差,Sakila将何去何从?

- 2024-06-18 让PG停摆一周的大会:PGCon.Dev参会记

- 2024-05-29 PGCon.Dev 2024 温哥华扩展生态峰会小记

- 2024-05-24 PostgreSQL 17 Beta1 发布!牙膏管挤爆了!

- 2024-05-16 为什么PostgreSQL是未来数据的基石?

- 2024-04-25 国产数据库到底能不能打?

- 2024-03-28 PostgreSQL 主要贡献者 Simon Riggs 因坠机去世

- 2024-03-26 Redis不开源是“开源”之耻,更是公有云之耻

- 2024-03-24 PostgreSQL会修改开源许可证吗?

- 2024-03-16 PostgreSQL is eating the database world

- 2024-03-14 RDS阉掉了PostgreSQL的灵魂

- 2024-03-04 PostgreSQL正在吞噬数据库世界

- 2024-02-19 技术极简主义:一切皆用Postgres

- 2024-02-18 PG生态新玩家ParadeDB

- 2024-02-02 DBA会被云淘汰吗?

- 2024-01-14 快速掌握PostgreSQL版本新特性

- 2024-01-13 令人惊叹的PostgreSQL可伸缩性

- 2024-01-11 国产数据库是大炼钢铁吗?

- 2024-01-08 中国对PostgreSQL的贡献约等于零吗?

- 2024-01-05 展望PostgreSQL的2024 (Jonathan Katz)

- 2024-01-03 2023年度数据库:PostgreSQL (DB-Engine)

- 2023-12-31 2023总结:三十而立

- 2023-12-30 MySQL的正确性为何如此拉垮?

- 2023-12-05 数据库应该放入K8S里吗?

- 2023-12-04 把数据库放入Docker是一个好主意吗?

- 2023-11-22 向量数据库凉了吗?

- 2023-11-17 重新拿回计算机硬件的红利

- 2023-11-02 数据库真被卡脖子了吗?

- 2023-10-26 PG查询优化:观宏之道

- 2023-10-09 EL系操作系统发行版哪家强?

- 2023-10-08 FerretDB:假扮成MongoDB的PostgreSQL?

- 2023-09-27 如何用 pg_filedump 抢救数据?

- 2023-09-26 PGSQL x Pigsty: 数据库全能王来了

- 2023-09-10 PG先写脏页还是先写WAL?

- 2023-09-08 冯若航:不想当段子手的技术狂,不是一位好的开源创始人

- 2023-08-31 基础软件到底需要什么样的自主可控?

- 2023-08-11 如何看待 MySQL vs PGSQL 直播闹剧

- 2023-08-09 驳《MySQL:这个星球最成功的数据库》

- 2023-08-06 向量是新的JSON

- 2023-06-27 ISD数据集:分析全球120年气候变化

- 2023-05-10 AI大模型与向量数据库 PGVECTOR

- 2023-05-09 技术反思录:正本清源 之 序章

- 2023-05-07 微服务是不是个蠢主意?

- 2023-04-17 分布式数据库是伪需求吗?

- 2023-04-10 AI 会有自我意识吗?

- 2023-03-29 数据库需求层次金字塔

- 2023-03-01 驳《再论为什么你不应该招DBA》

- 2023-01-31 云数据库是不是杀猪盘

- 2023-01-31 你怎么还在招聘DBA? 马工

- 2023-01-30 云数据库是不是智商税

- 2022-08-22 PostgreSQL 到底有多强?

- 2022-07-12 为什么PostgreSQL是最成功的数据库?

- 2022-07-07 90后,辞职创业,说要卷死云数据库

- 2022-06-24 StackOverflow 2022数据库年度调查

- 2022-05-16 云RDS:从删库到跑路

- 2022-05-10 DBA还是一份好工作吗?

- 2021-05-08 为什么说PostgreSQL前途无量?

小数据的失落十年:分布式分析的错付

如果 2012 年 DuckDB 问世,也许那场数据分析向分布式架构的大迁移根本就不会发生。通过在2012年的Macbook笔记本上运行 TPC-H 评测,我们发现数据分析确实在分布式架构上走了十年弯路。

作者: Hannes Mühleisen,发布于 2025 年 5 月 19 日,英文

译评:冯若航,数据库老司机,云数据库泥石流

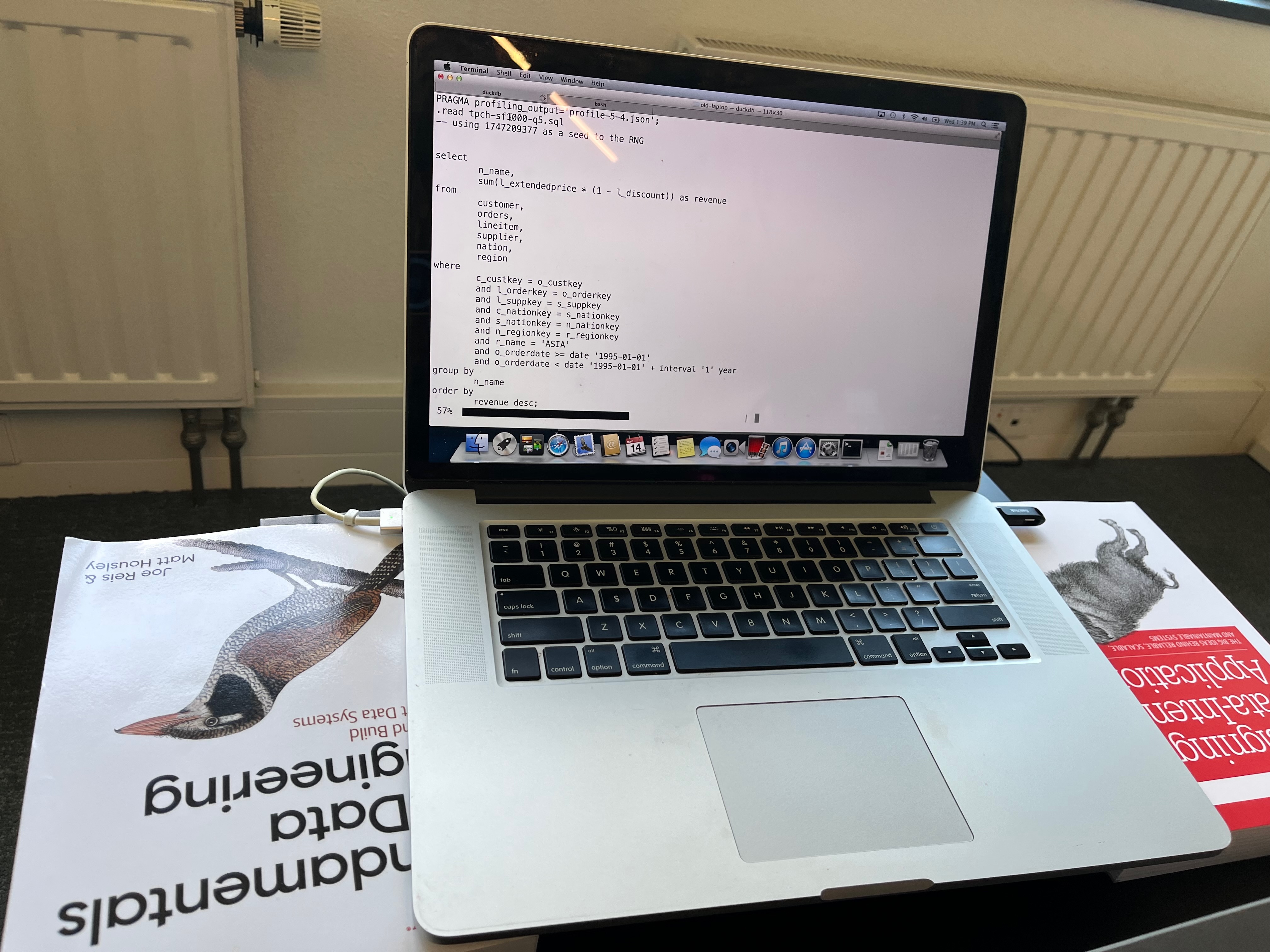

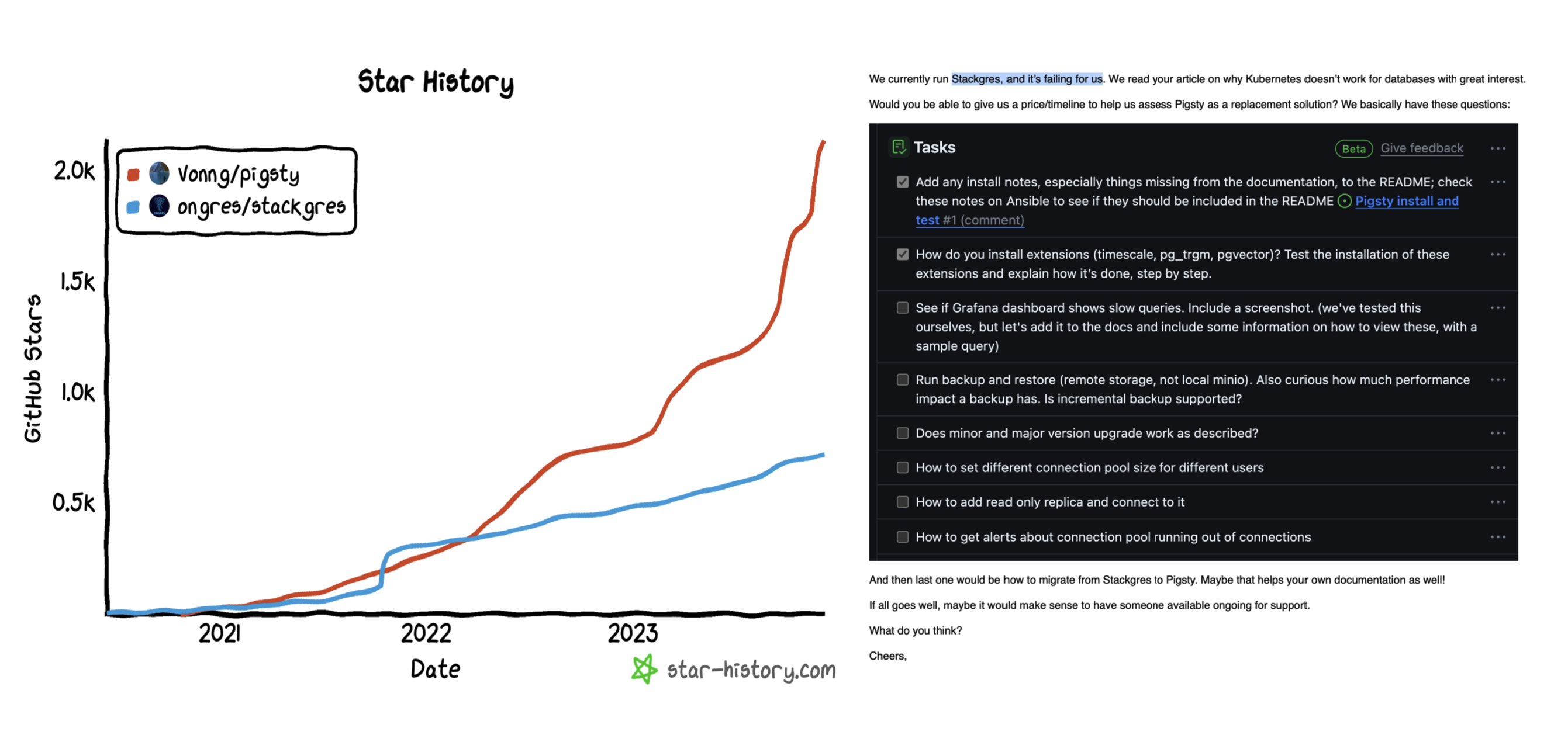

太长不看:我们在一台 2012 年款 MacBook Pro 上对 DuckDB 进行了基准测试,想要弄清楚在过去十年里,我们是否在追逐分布式数据分析架构的过程中迷失了方向?

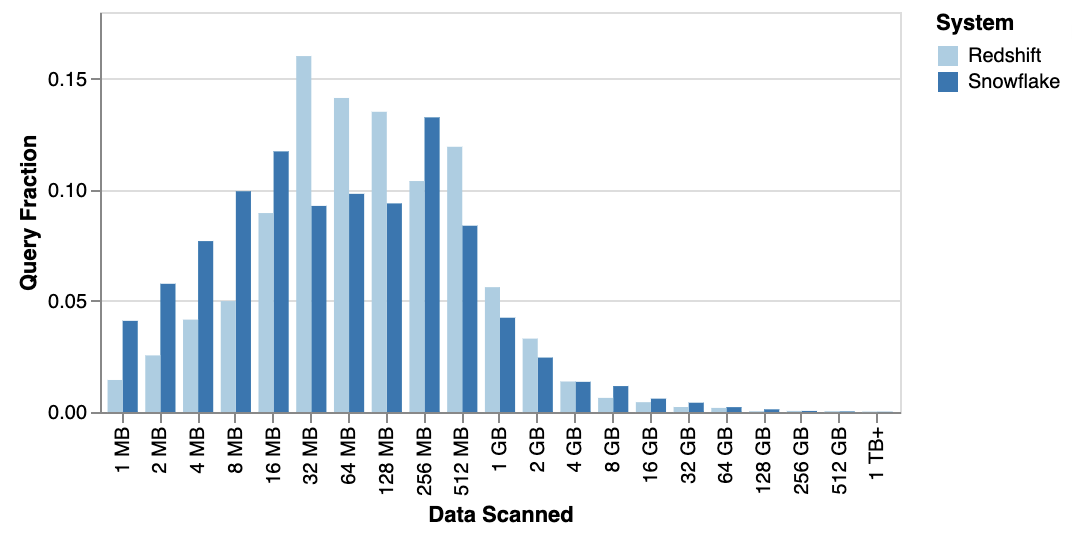

包括我们自己在内,很多人都反复提到过这一点:数据其实没那么大 。 而且硬件进步的速度已经超越了有用数据集规模的增长速度。我们甚至预测预测过 在不久的将来会出现“数据奇点” ——届时 99% 的有用数据集都能在单节点上轻松查询。最近的研究数据显示 , Amazon Redshift 和 Snowflake 上的查询中位扫描数据量仅约 100 MB,而 99.9 百分位点也不到 300 GB。由此看来,“奇点”也许比我们想象的更近。

但是我们开始好奇,这一趋势究竟是从什么时候开始的?像随处可见、通常只用来跑 Chrome 浏览器的 MacBook Pro 这样的个人电脑,是什么时候摇身一变成为了如今的数据处理大师?

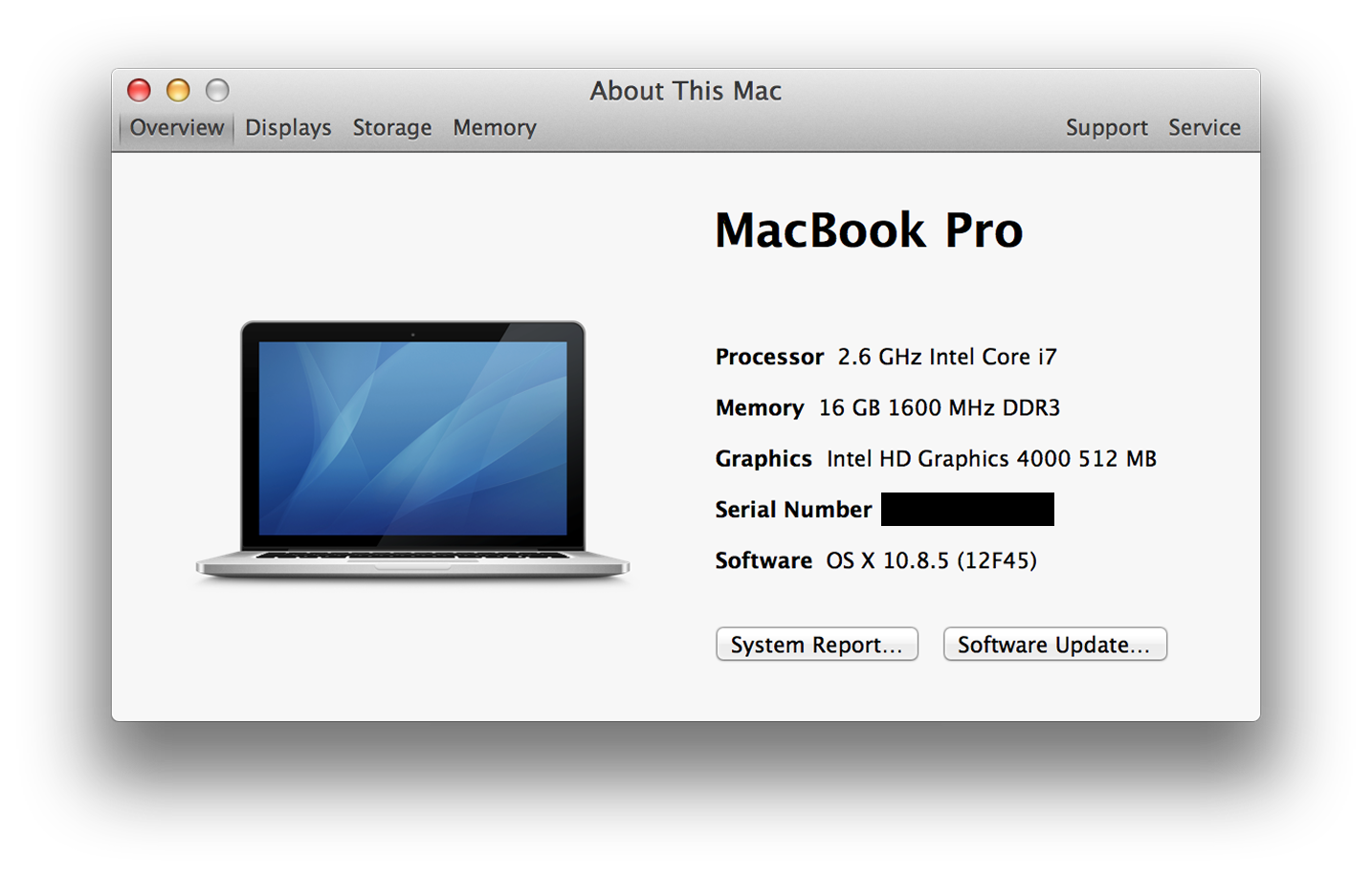

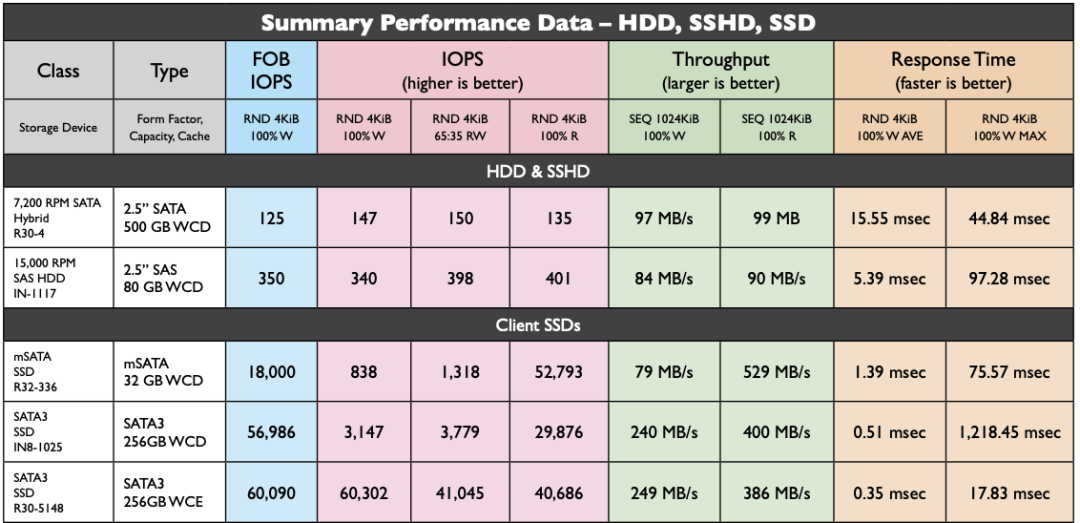

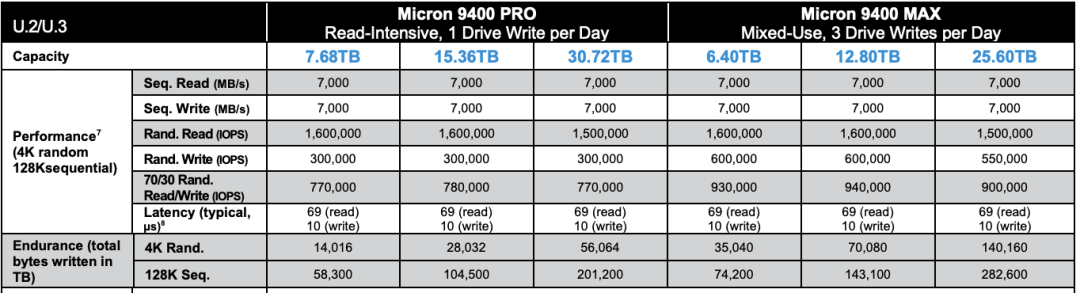

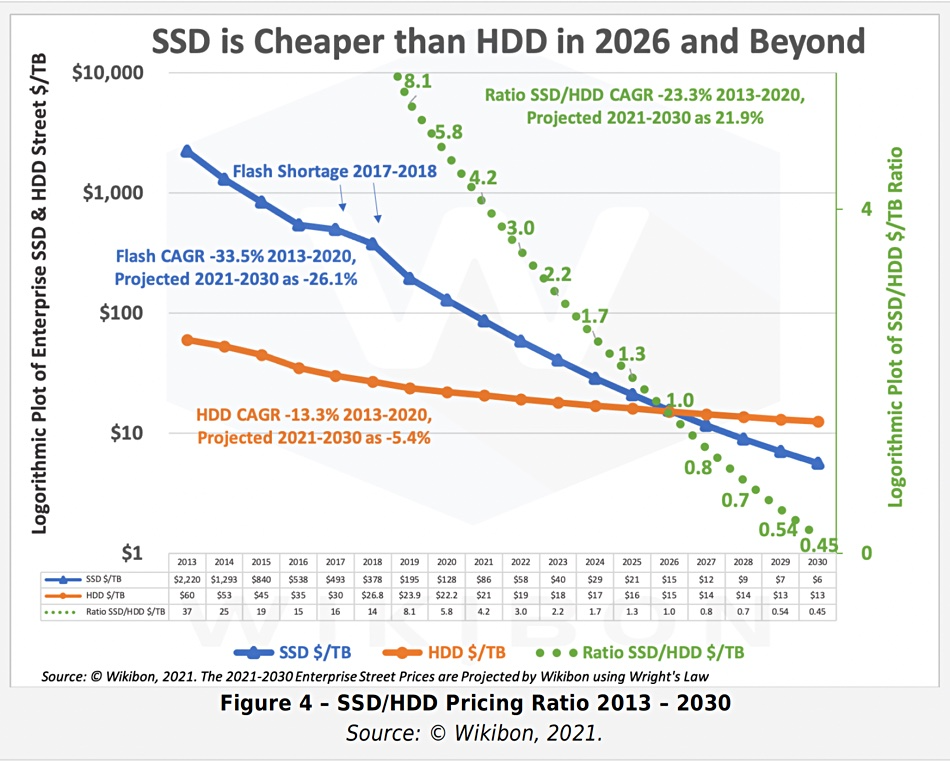

让我们把目光投向 2012 年的 Retina MacBook Pro。许多人(包括我自己)当年购买这款电脑是为了它那块华丽的 “Retina”(视网膜) 显示屏 —— 销量以百万计。我当时虽没工作,但还是咬牙加钱把内存升级到了 16 GB。不过,这台机器上还有一个常被遗忘的革命性变化:它是第一款内置固态硬盘(SSD)并配备性能强劲的 4核 2.6 GHz Core i7 CPU 的 MacBook。重看一遍当年的 发布会视频 仍然颇为有趣 —— 他们 确实 也强调了这种 “全闪存架构” 的性能优势。

题外话:实际上早在 2008 年 MacBook Air 就已经是第一款可选配内置 SSD 的 MacBook,只可惜它没有 Pro 版那样强劲的 CPU 火力。

巧的是,我现在手头仍有这样一台笔记本放在 DuckDB Labs 办公室,我的孩子们平时来玩时,会用它来刷 Youtube 看动画片。那么,这台老古董还跑得动现代版本的 DuckDB 吗?它的性能和现代的 MacBook 相比如何? 我们可以在 2012 年就迎来当今的数据革命吗?让我们一探究竟!

软件

首先来说说操作系统。为了让这次跨年代的对比更公平,我们特地把 Retina 本的系统 降级 到 OS X 10.8.5 “Mountain Lion”——这正是该笔记本上市几周后的 2012 年 7 月发布的操作系统版本。虽然这台 Retina 笔记本实际上可以运行 10.15 (Catalina),但我们觉得要做真正的 2012 年对比,就该使用那个年代的操作系统。下面这张截图展示了当年的系统界面,我们这些上了年纪的人看了不禁有点感慨。

再来说 DuckDB 本身。在 DuckDB 团队,我们对可移植性和依赖有着近乎宗教般的坚持(更准确的说是 “零依赖”)。正因如此,要让 DuckDB 在古老的 Mountain Lion 上跑起来几乎不费吹灰之力:DuckDB 的预编译二进制默认兼容到 OS X 11.0 (Big Sur),我们只需调整一个编译标志重新编译,就使 DuckDB 1.2.2 顺利运行在了 Mountain Lion 上。我们本想尝试用 2012 年的老旧编译器来构建 DuckDB,无奈 C++11 在当年还太新,编译器对它的支持根本跟不上。话虽如此,生成的二进制运行良好——实际上,只要费些功夫绕过编译器的几个 bug,当年也是可以把它编译出来的。或者,我们大可以像 其他人那样 干脆直接手写汇编。

基准测试

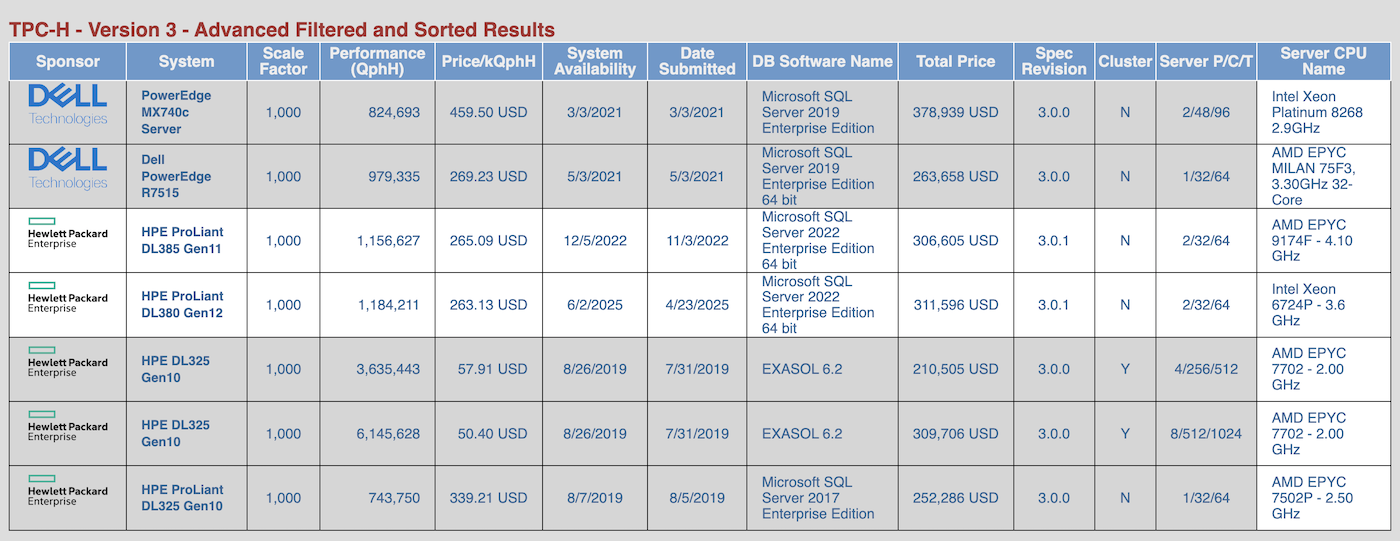

但我们感兴趣的可不是什么 CPU 综合跑分,我们关注的是 SQL综合跑分!为了检验这台老机器在严肃的数据处理任务下的表现,我们使用了如今已经有些老掉牙但依然常用的 TPC-H 基准测试,规模因子设为 1000。这意味着其中两张主要表 lineitem 和 orders 分别包含约 60 亿和 15 亿行数据。将数据生成 DuckDB 数据库文件后,大约有 265 GB 大小。

根据 TPC 官网的审计结果 ,可以看出在单机上跑如此规模的基准测试,似乎需要价值数十万美元的硬件设备。

我们将 22 个基准查询各跑了五遍,取中位数运行时间来降噪。(由于内存只有 16 GB,而数据库大小达到 256 GB,缓冲区几乎无法缓存多少输入数据,因此这些严格来说都算不上大家口中的 “热运行“。)

下面列出了每个查询的耗时(单位:秒):

| 查询 | 耗时 |

|---|---|

| 1 | 142.2 |

| 2 | 23.2 |

| 3 | 262.7 |

| 4 | 167.5 |

| 5 | 185.9 |

| 6 | 127.7 |

| 7 | 278.3 |

| 8 | 248.4 |

| 9 | 675.0 |

| 10 | 1266.1 |

| 11 | 33.4 |

| 12 | 161.7 |

| 13 | 384.7 |

| 14 | 215.9 |

| 15 | 197.6 |

| 16 | 100.7 |

| 17 | 243.7 |

| 18 | 2076.1 |

| 19 | 283.9 |

| 20 | 200.1 |

| 21 | 1011.9 |

| 22 | 57.7 |

但是,这些冰冷的数字实际上意味着什么呢?令人窃喜的是,这台老电脑居然真的用 DuckDB 跑完了所有基准查询!如果仔细看看那些耗时,每个查询大致在几分钟到半小时之间。这种数据量下跑分析型查询,这样的等待时间一点也不离谱。老天,要是在 2012 年,你光等 Hadoop YARN 去调度你的作业就得更久,最后很可能它只会朝你吐出一堆错误堆栈。

2023 年的改进

那么这些结果与一台当代 MacBook 比又如何呢?作为比较,我们使用了一台现代 ARM 架构 M3 Max MacBook Pro(碰巧就在同一张桌子上)。这两台 MacBook 之间代表了超过十年的硬件发展差距。

从 GeekBench 5 基准测试分数 来看,全核性能提升了约 7 倍,单核性能提升约 3 倍。当然,RAM 和 SSD 速度的差距也非常明显。有趣的是,屏幕尺寸和分辨率几乎没有变化。

下面将两台机器的结果并排列出:

| 查询 | 旧耗时 | 新耗时 | 加速比 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 142.2 | 19.6 | 7.26 |

| 2 | 23.2 | 2.0 | 11.60 |

| 3 | 262.7 | 21.8 | 12.05 |

| 4 | 167.5 | 11.1 | 15.09 |

| 5 | 185.9 | 15.5 | 11.99 |

| 6 | 127.7 | 6.6 | 19.35 |

| 7 | 278.3 | 14.9 | 18.68 |

| 8 | 248.4 | 14.5 | 17.13 |

| 9 | 675.0 | 33.3 | 20.27 |

| 10 | 1266.1 | 23.6 | 53.65 |

| 11 | 33.4 | 2.2 | 15.18 |

| 12 | 161.7 | 10.1 | 16.01 |

| 13 | 384.7 | 24.4 | 15.77 |

| 14 | 215.9 | 9.2 | 23.47 |

| 15 | 197.6 | 8.2 | 24.10 |

| 16 | 100.7 | 4.1 | 24.56 |

| 17 | 243.7 | 15.3 | 15.93 |

| 18 | 2076.1 | 47.6 | 43.62 |

| 19 | 283.9 | 23.1 | 12.29 |

| 20 | 200.1 | 10.9 | 18.36 |

| 21 | 1011.9 | 47.8 | 21.17 |

| 22 | 57.7 | 4.3 | 13.42 |

显而易见,我们获得了可观的加速效果,最低约 7 倍,最高超过 50 倍。运行时间的几何平均数 从 218 秒降低到了 12 秒,整体提升了约 20 倍。

可复现性

所有二进制文件、脚本、查询和结果都已发布在 GitHub 上供大家查阅。我们还提供了 TPC-H SF1000 数据库文件 下载,这样你就不用自己生成。不过请注意,文件非常大。

讨论

我们看到,这台已有十年历史的 Retina MacBook Pro 成功完成了复杂的分析型基准测试,而更新的笔记本则显著缩短了运行时间。但对于用户而言,那些绝对的加速倍数其实意义不大—— 这里的差别纯粹是 量变 而非什么 质变。

从用户的角度来看,更重要的是这些查询能够在相当合理的时间内完成,而不是纠结于到底用了 10 秒还是 100 秒。用这两台笔记本,我们几乎可以解决同样规模的数据问题,只不过旧机器需要我们多等待一会儿而已。尤其是 DuckDB 能够处理超出内存大小的数据集——必要时可以将查询中间结果溢出到磁盘,这让单机处理大数据成为可能。

更有意思的是,早在 2012 年,像 DuckDB 这样单机 SQL 引擎完全有能力在可接受的时间内跑完对一个包含 60 亿行数据的数据库的复杂分析查询——而这一次我们甚至不需要 把机器泡在干冰里。

历史不乏各种 **“假如当初……” **的假设。如果 2012 年就出现了 DuckDB,会发生什么呢?主要的条件那时其实都已具备—— 矢量化查询处理技术早在2005年就已经问世。如今回头再看那场数据分析向分布式架构的大迁移显得有些傻气,如果那时候就有 DuckDB,也许那场运动根本不会发生。

我们这次使用的基准数据集规模,非常接近 2024 年分析查询输入数据量的 99.9 百分位点。而 Retina MacBook Pro 虽然在 2012 年属于高端机型,但到了 2014 年,许多厂商提供的笔记本电脑也都配备了内置 SSD,且更大容量的内存逐渐变得司空见惯。

所以,没错,我们的确整整浪费了十年。

老冯评论

老冯一直认为在当代硬件条件下,分布式数据库是一个伪需求。在《分布式数据库是伪需求吗?》那篇文章中,我比较保守的将 “OLAP 分析” 从中排除 —— 因为我确实在阿里处理过单机没法搞的数据量级 —— 每天 70 TB 的全网 PV 日志。

但我必须承认,那种情况真的属于极端特例,实际上绝大多数的分析场景并不会有那么多的数据。毕竟根据各种数据泄漏案例来看,全国人口数据,GA 全量结构数据,也就两百多个 GB 而已。许多所谓的“大数据场景” 其实并没有那么多数据,每次查询的时候实际读取处理的数据就更少了。(请看《DuckDB宣言:大数据已死》)

DuckDB 的这篇文章无疑撕开了整个数据分析,分布式数据库与大数据行业的遮羞布。是的,早在十年前,像几百 GB 的全量分析,就已经可以在一台 Macbook 笔记本上进行了!我们确实整整浪费了十年的时间,在错误的道路上蹉跎了岁月。

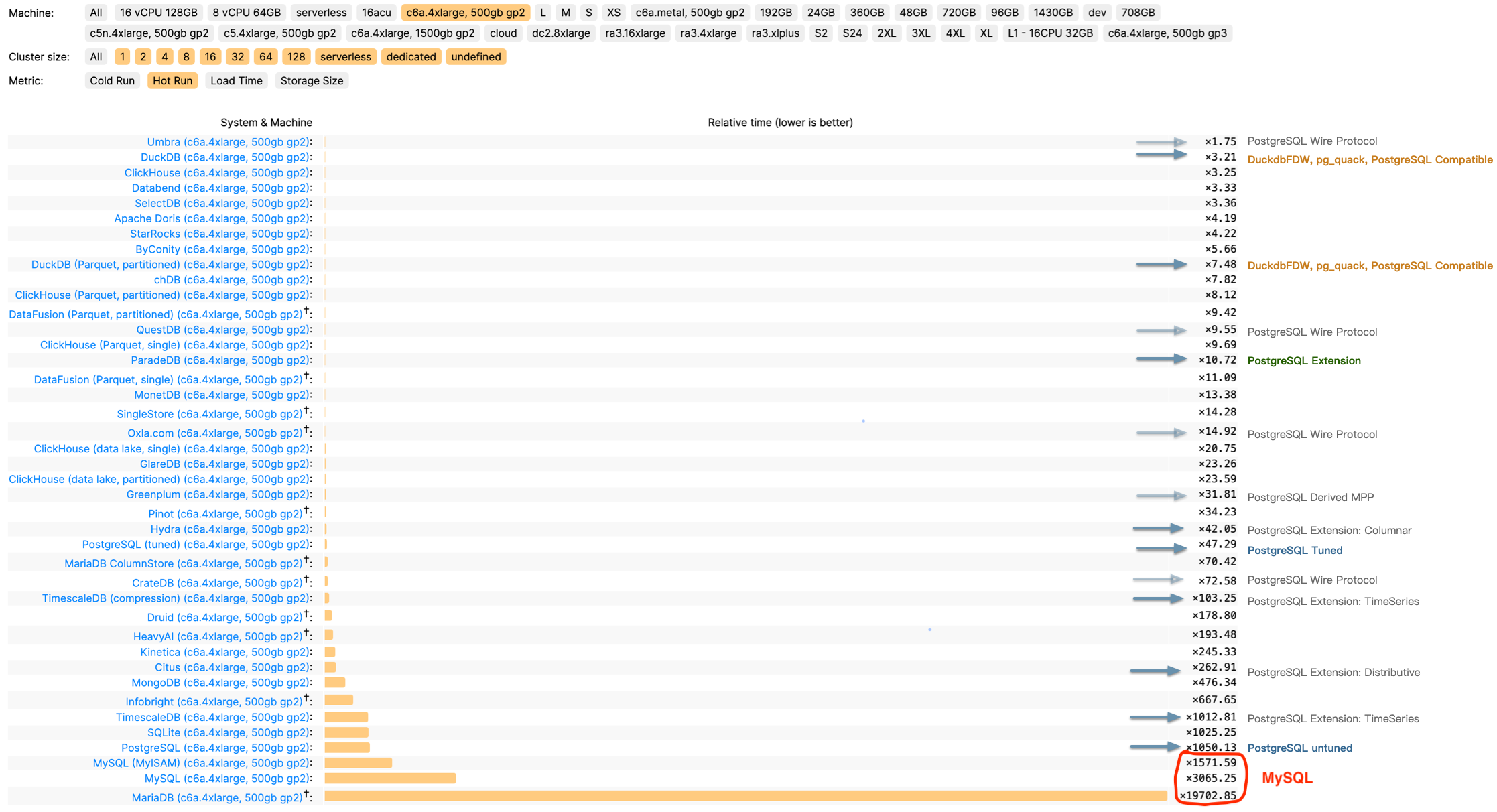

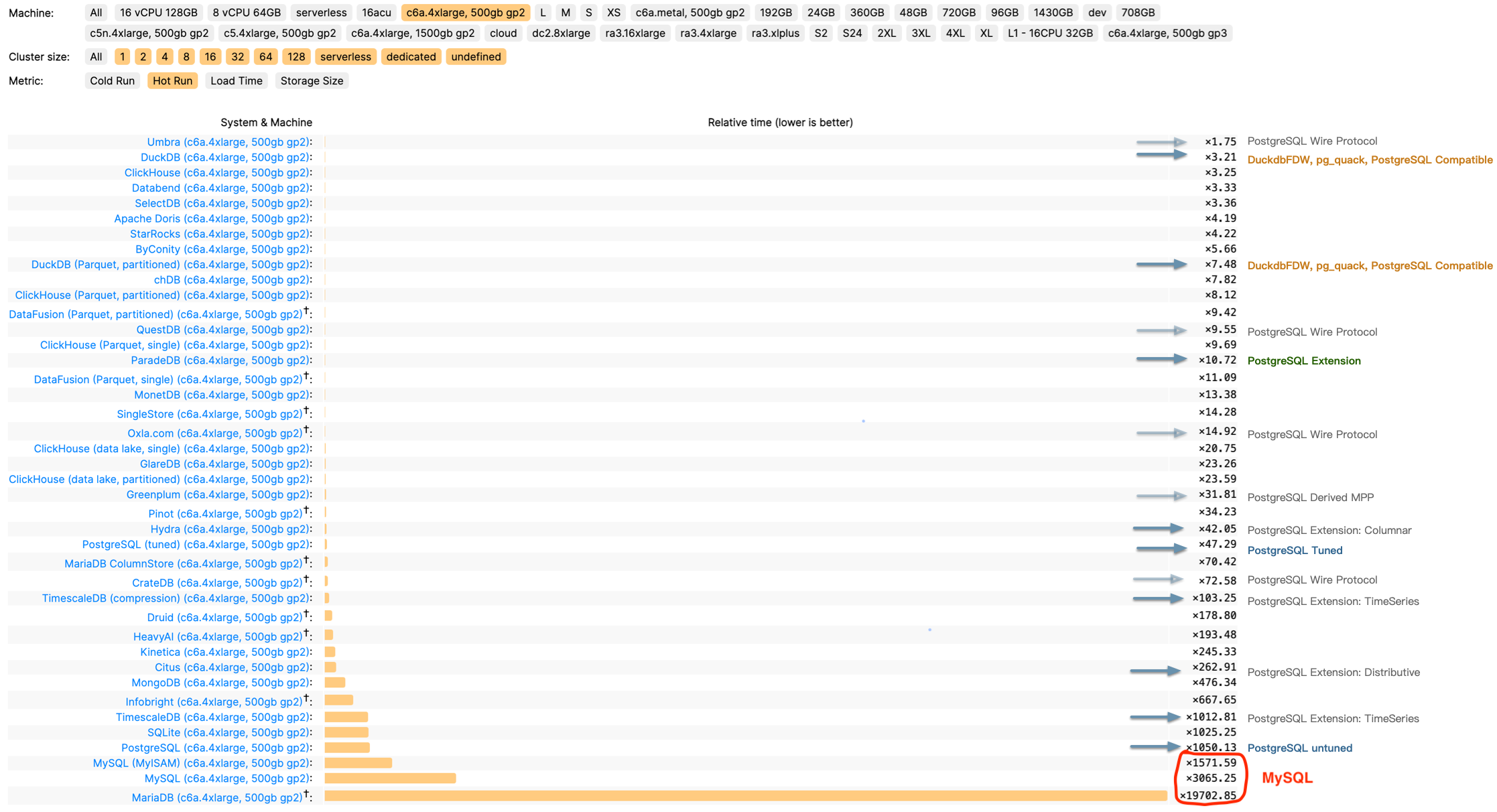

我的意思是,TPC-H 1000 仓的分析,可以在一台普通笔记本上用 6 分钟(370s)跑完,在十年前的笔记本上用 6 小时(8344s)跑出来,这是一个惊人的成绩。如果我们把现在的各路分布式数据库,OLAP,HTAP,MPP 各种 P 拉出来对比一下的话,就不难发现这是多么惊人的一个成绩了。

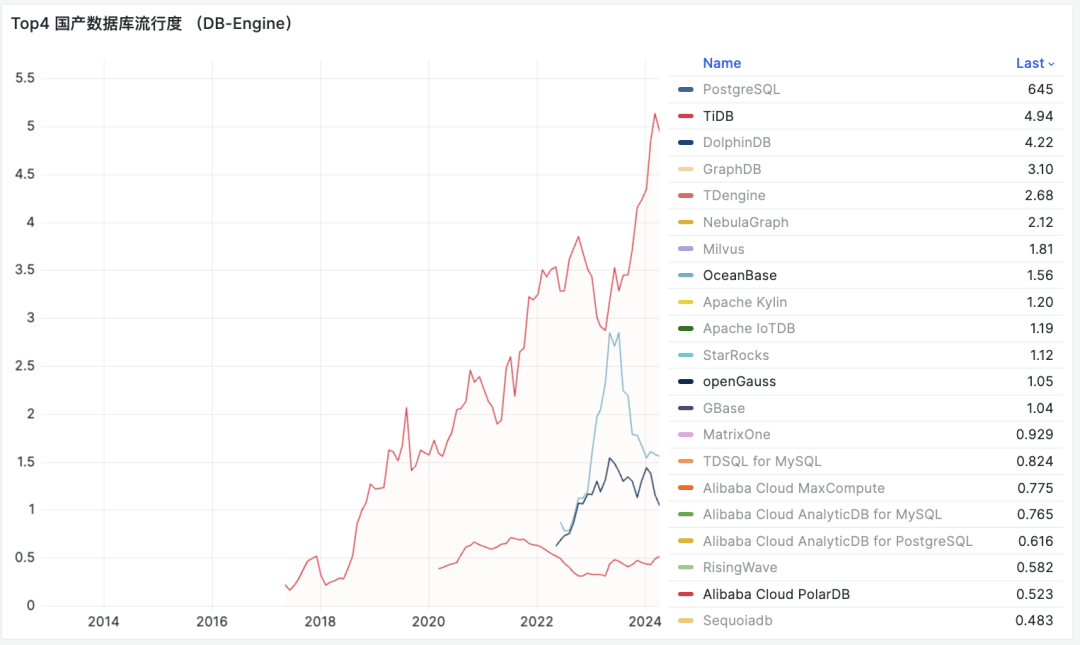

例如国产数据库标杆 TiDB 主打 HTAP 概念,并提供了 TiFlash 用于分析加速。然而其官网公布的 TPC-H 评测结果,用 92C 478G 处理 50 仓的数据,耗时几乎和一台 10C64GB 笔记本处理 300 仓的接近,在相同的时间里用十倍的资源却只处理了 1/6 的数据。这不禁让人怀疑,在这里用分布式真的有意义吗?

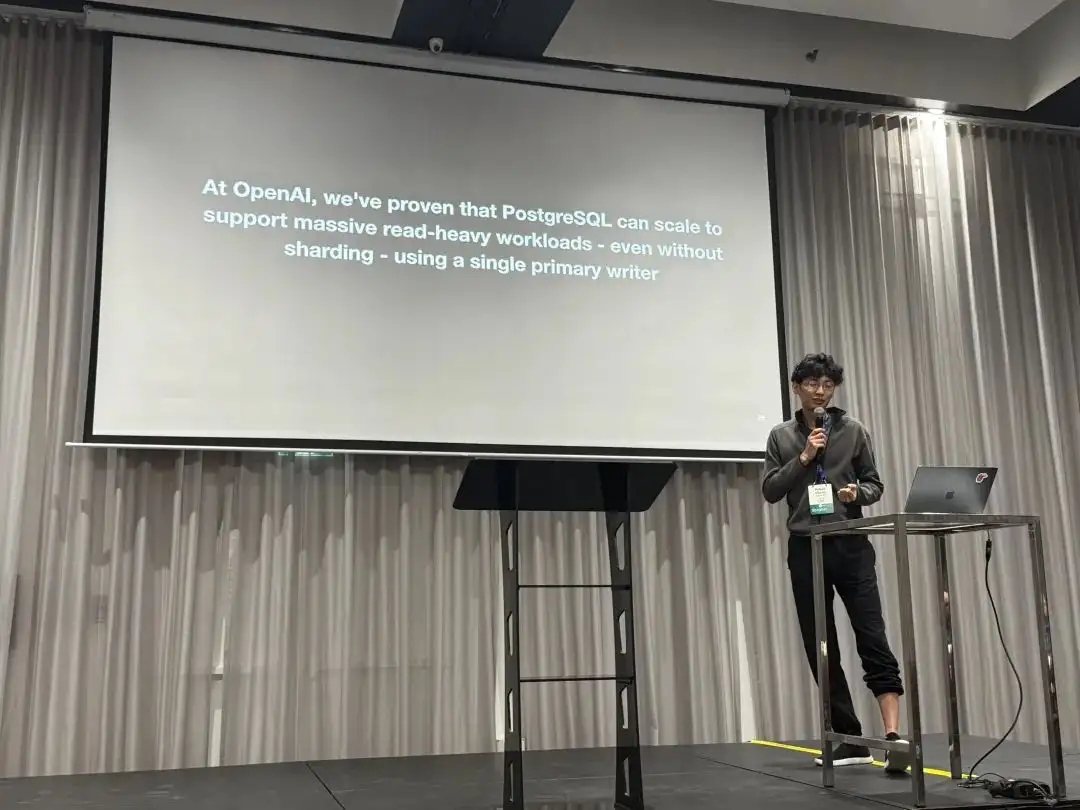

有人说 OLTP 也许会有超出单机吞吐的情况必须要用到分布式数据库,可是拥有五亿活跃用户的 OpenAI 竟然只用了一套 1主40从的 PostgreSQL 集群,在未分片的情况下直接支撑起了整个业务(《OpenAI:将PostgreSQL伸缩至新阶段》)。如果 OpenAI 能用集中式架构做到这一点,我相信你的业务也一定可以。

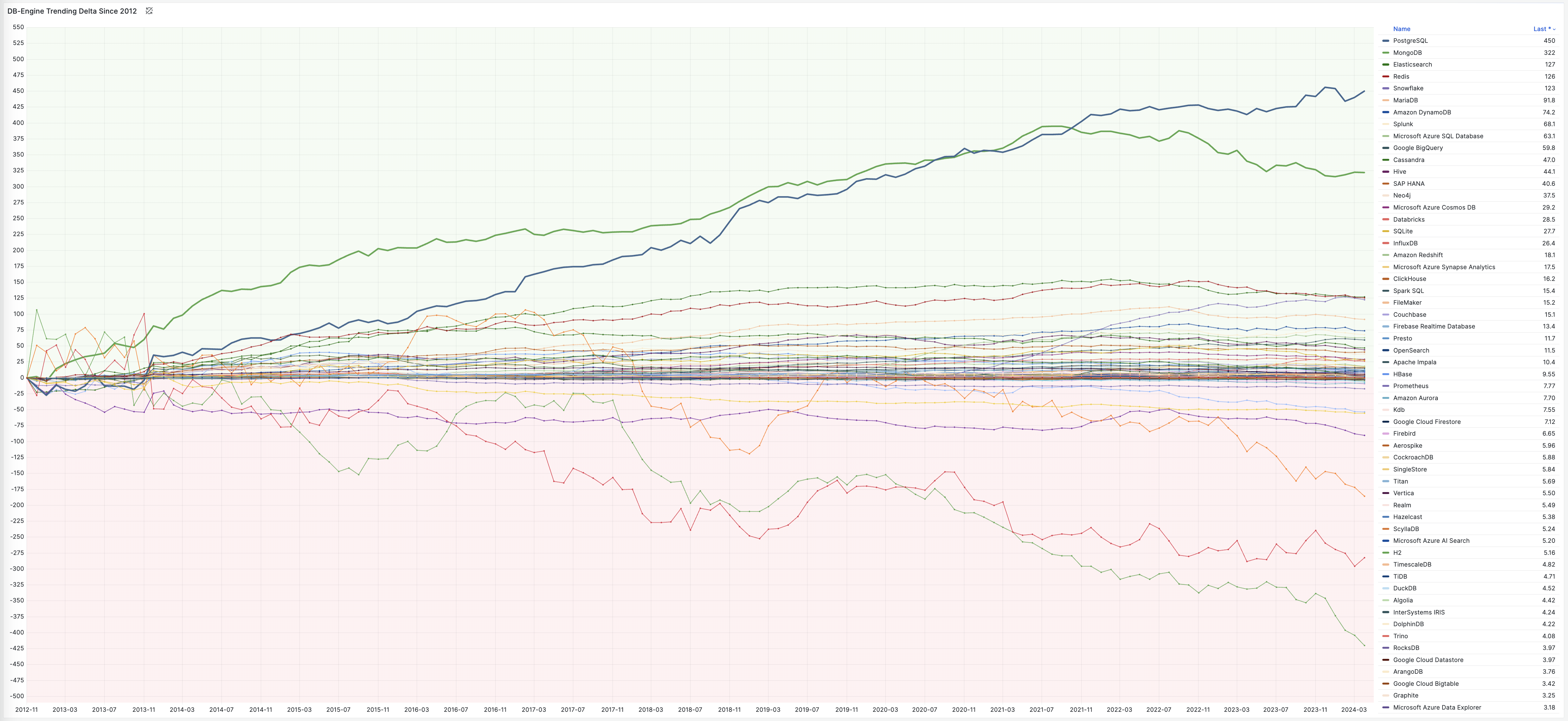

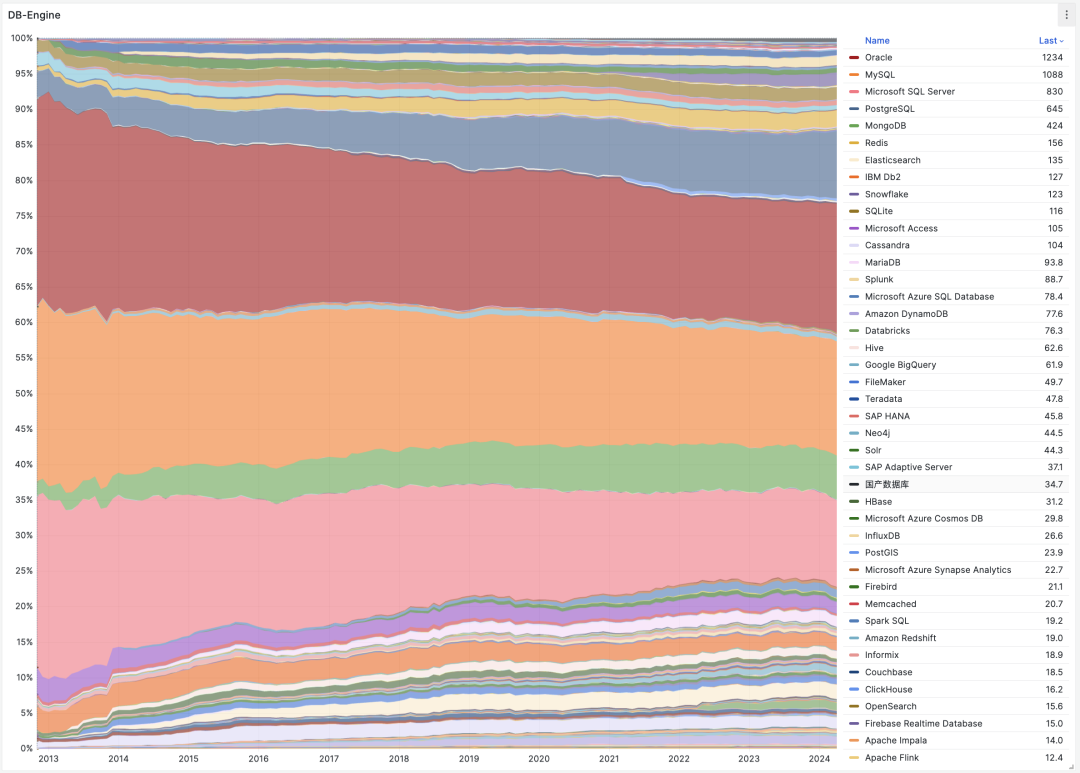

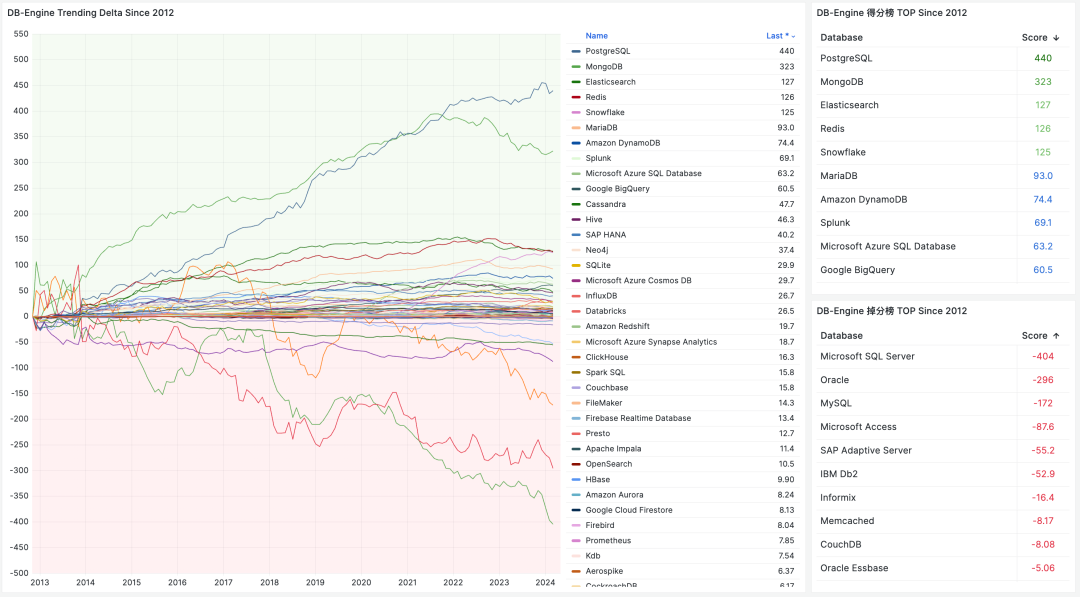

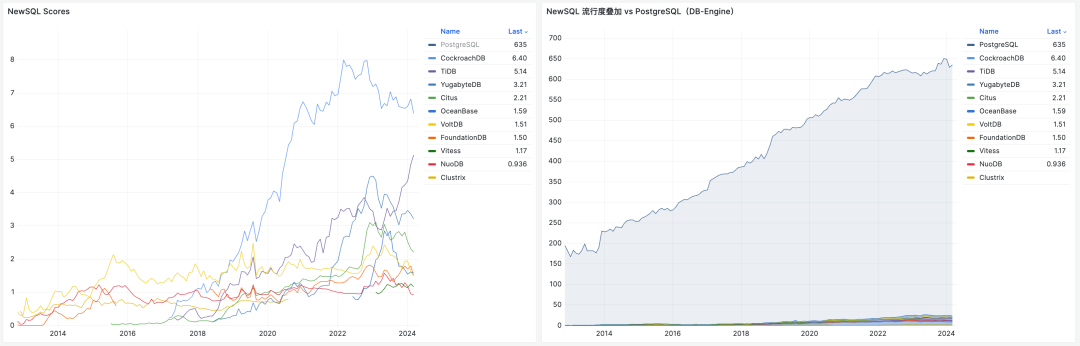

DuckDB 的例子进一步证明了在当代,分布式数据库已经成为了伪需求 —— 不仅仅是 OLTP,甚至是 OLAP。实际上如果我们关注 DB-Engine 上的热度就不难发现,分布式数据库作为一个 Niche(NewSQL),甚至都还没有像产生像 NoSQL 这样的影响力,就已经过气了。而我相信,重新融合 OLTP 和 OLAP 的新物种,将由 PostgreSQL 和 DuckDB 杂交而出。

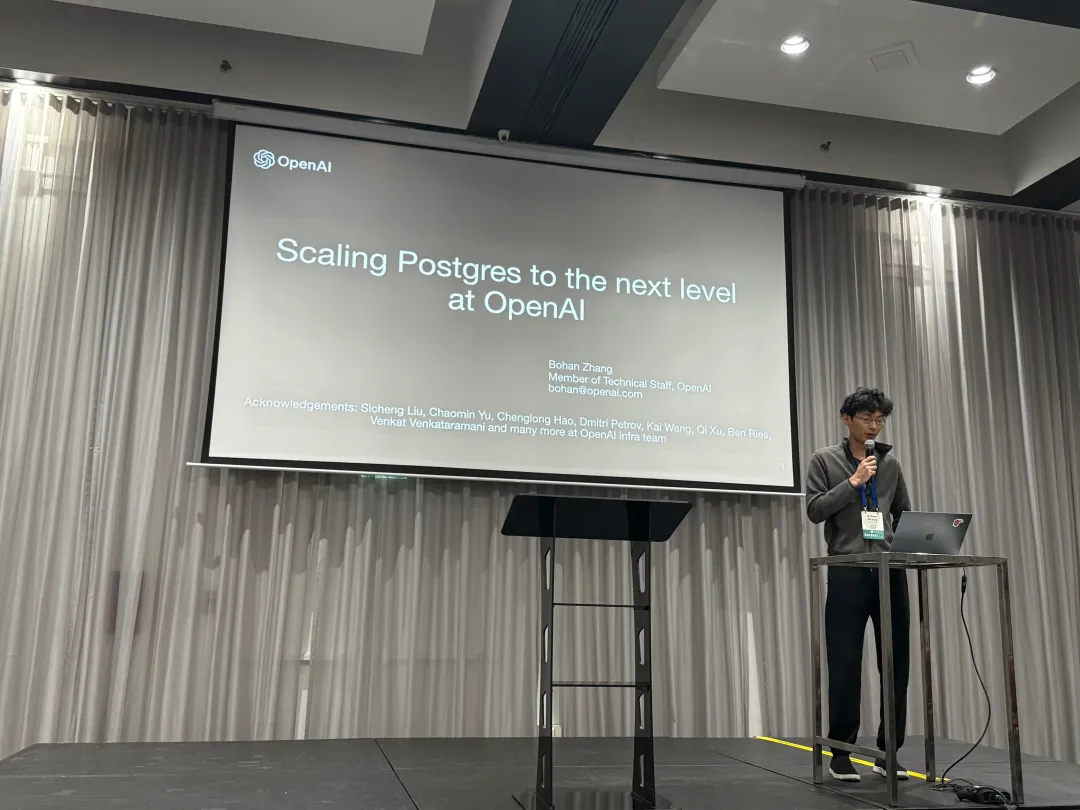

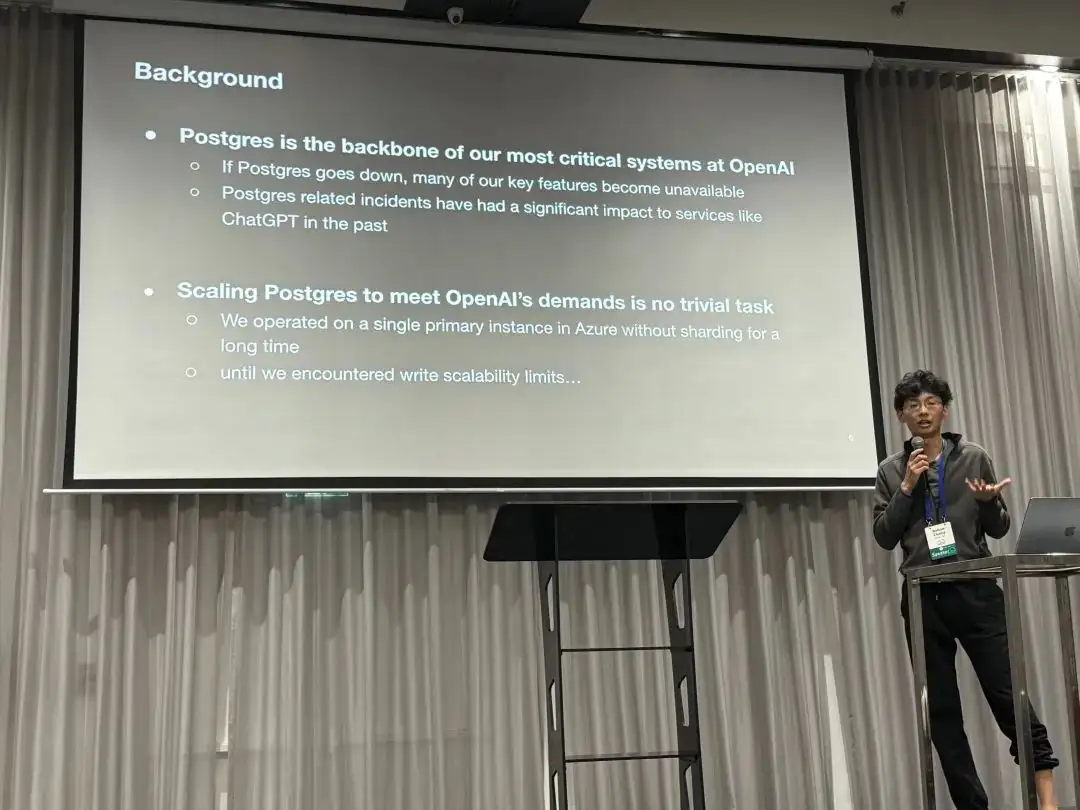

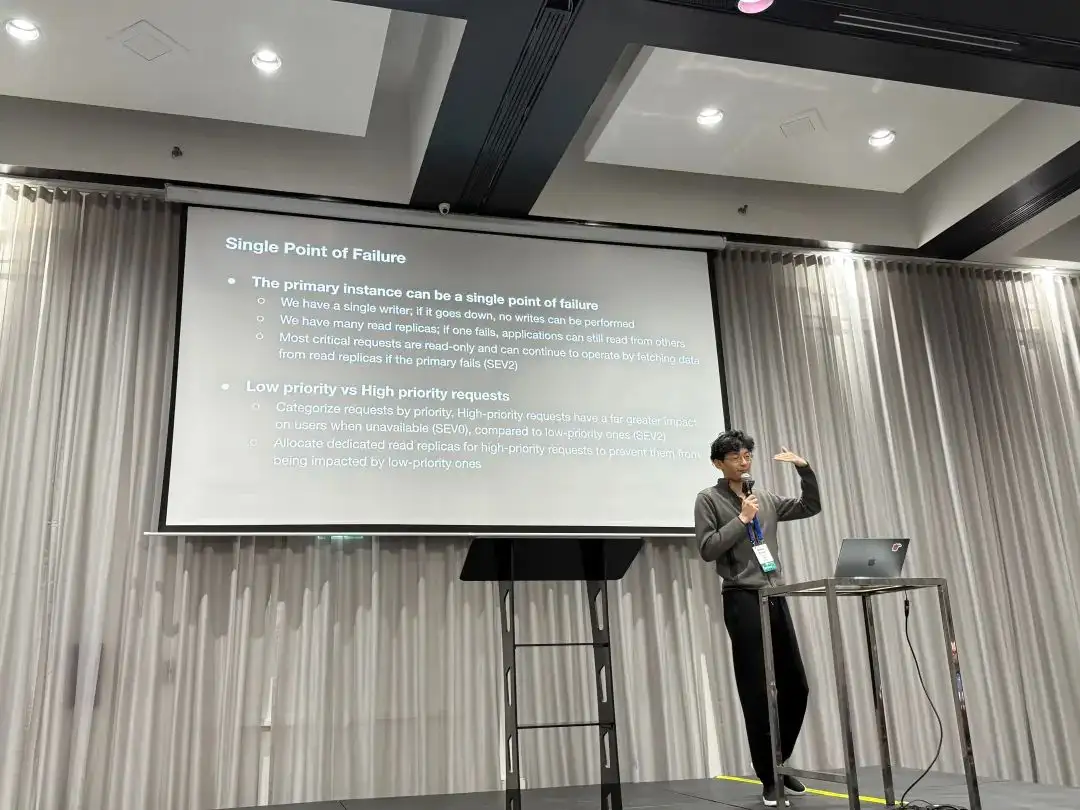

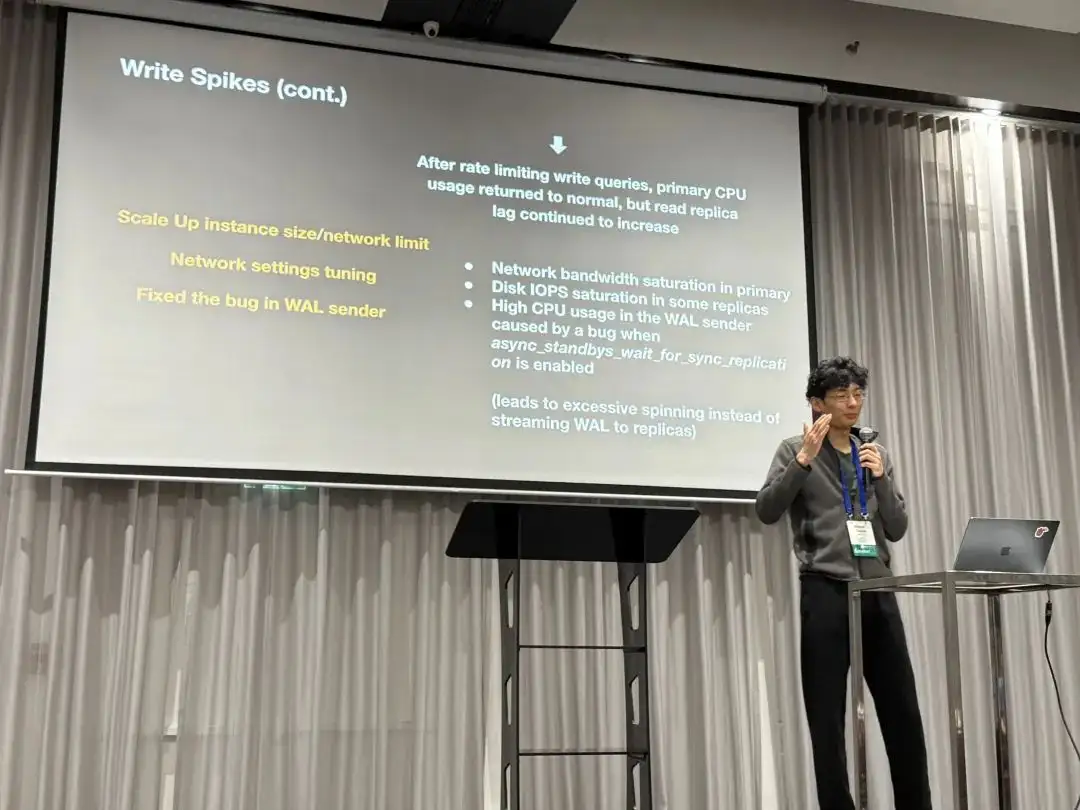

OpenAI:将PostgreSQL伸缩至新阶段

在 PGConf.Dev 2025 全球 PG 开发者大会上, 来自 OpenAI 的 Bohan Zhang 分享了 OpenAI 在 PostgreSQL 上的最佳实践, 让我们得以一窥最牛独角兽内部的数据库使用情况。

“在 OpenAI,我们在使用一写多读的未分片架构,证明了 PostgreSQL 在海量读负载下也可以伸缩自如”

—— PGConf.Dev 2025 Bohan Zhang from OpenAI

Bohan Zhang 是 OpenAI Infra 组成员,师从 CMU 网红教授 Andy Pavlo ,并与其共同创办了 OtterTune 。本文为 Bohan 在大会上的演讲。 中文翻译/点评 by 冯若航:Pigsty 作者,PostgreSQL 老司机

Hacker News Discussion: OpenAI: Scaling Postgres to the Next Level

背景

PostgreSQL 是 OpenAI 绝大多数关键系统的核心支撑数据库,如果 Postgres 挂了,OpenAI 的很多关键服务就直接宕掉了 —— 而这是有不少先例的,PostgreSQL 相关的故障曾经在过去导致多次 ChatGPT 的故障。

OpenAI 使用 Azure 上的托管 PostgreSQL 数据库,没有使用分片与Sharding, 而是一个主库 + 四十多个从库的经典 PostgreSQL 主从复制架构。 对于像 OpenAI 这样拥有五亿活跃用户的服务而言,可伸缩性是一个重要的问题。

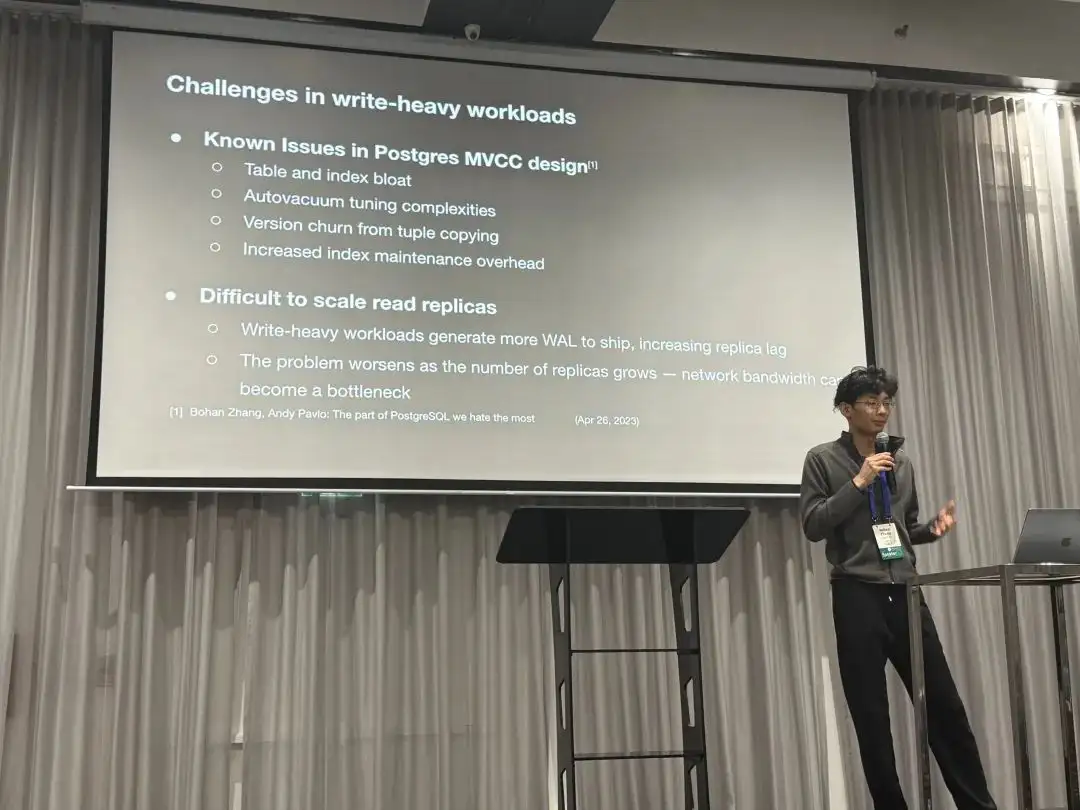

挑战

在 OpenAI 一主多从的 PostgreSQL 架构中,PG 的的读伸缩性表现极好,“写请求” 成为了一个主要的瓶颈。 OpenAI 已经在这上面进行了许多优化,例如将能移走的写负载尽可能移走,避免把新业务放进主数据库中。

PostgreSQL 的 MVCC 设计存在一些已知的问题,例如表膨胀与索引膨胀,自动垃圾回收调优较为复杂,每次写入都会产生一个完整新版本, 索引访问也可能需要额外的回表可见性检查。这些设计会带来一些 “扩容读副本” 的挑战: 例如更多 WAL 通常会导致复制延迟变大,而且当从库数量疯狂增长时,网络带宽可能成为新的瓶颈。

措施

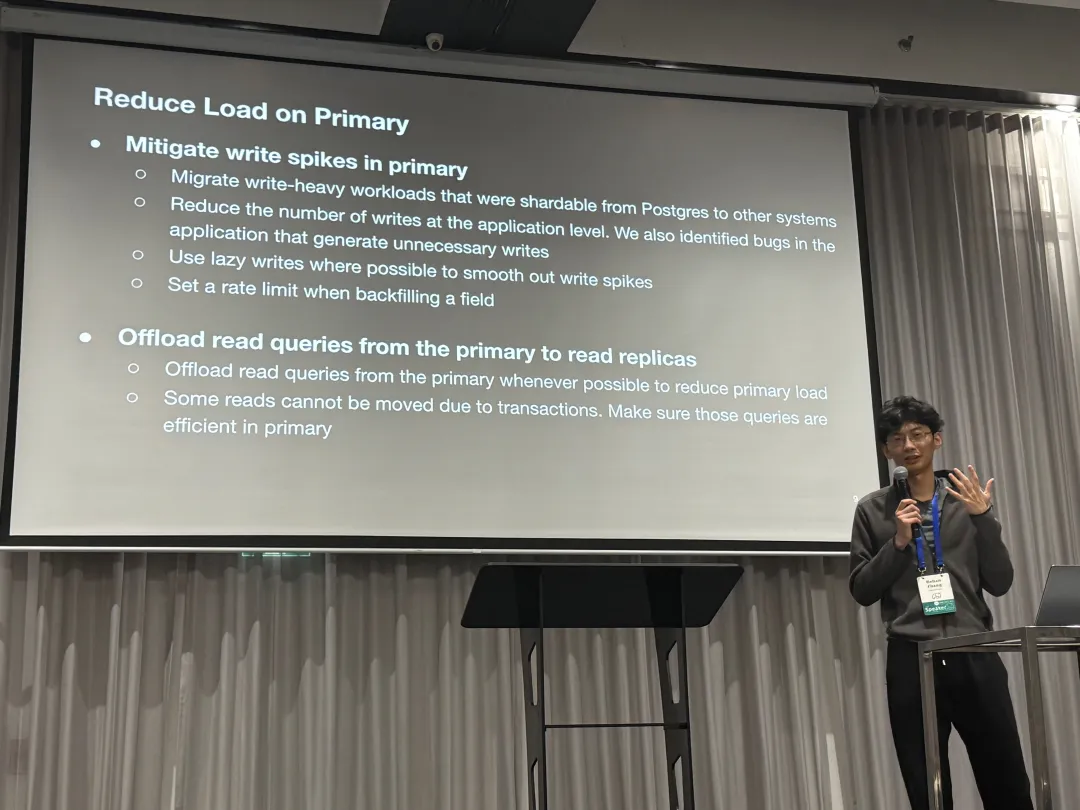

为了解决这些问题,我们进行了多个层面上的努力:

控制主库负载

第一项优化是抹平主库上的写尖峰,尽可能的减少主库上的负载,例如:

- 把能移走的写入统统移走

- 在应用层面尽可能避免不必要的写入

- 使用惰性写入来尽可能抹平写入毛刺

- 回填数据的时候控制频次

此外,OpenAI 还尽最大可能把读请求都卸载到从库上去,一些因为放在读写事务中,无法从主库上移除的读请求则要求尽可能高效。

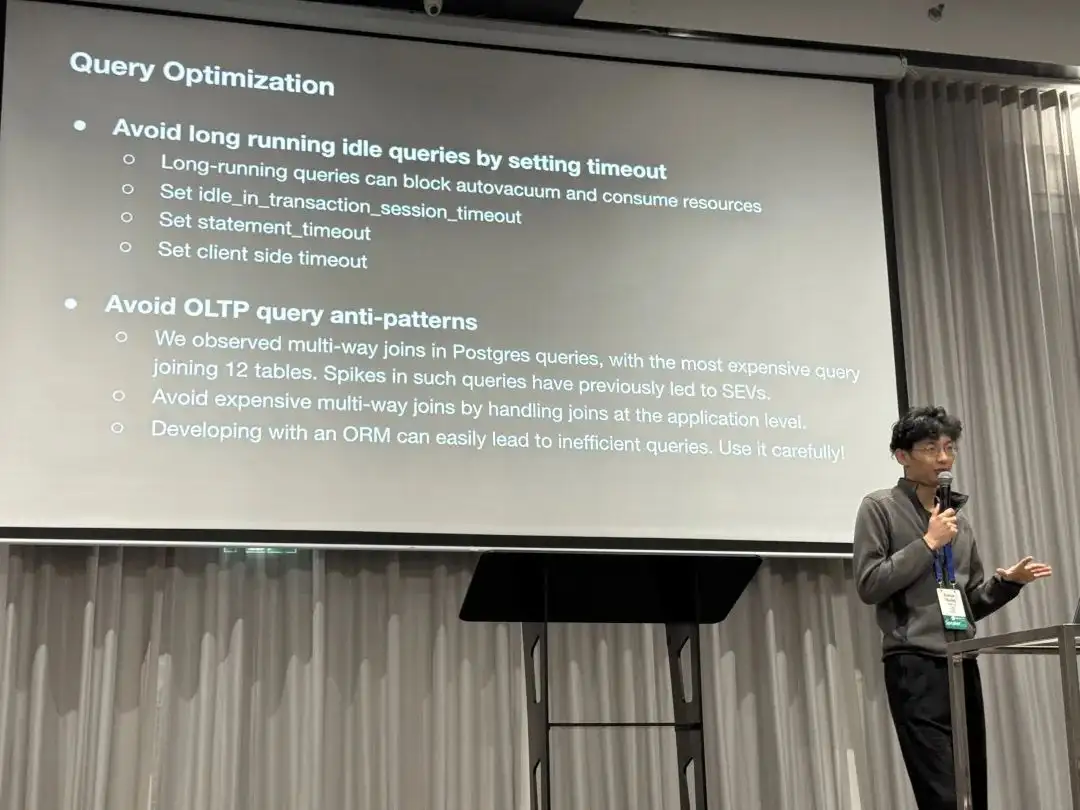

查询优化

第二项是在查询层面进行优化。因为长事务会阻止垃圾回收并消耗资源,因此他们使用 timeout 配置来避免 Idle in Transaction 长事务,并设置会话,语句,客户端层面的超时。 同时,还把一些多路 JOIN 的查询(比如一次 Join 12 个表)给优化掉了。分享中还特别提到使用 ORM 容易导致低效的查询,应当慎用。

治理单点问题

主库是一个单点,如果挂了就没法写入了。与之对应,我们有许多只读从库,一个挂了应用还可以读其他的。 实际上许多关键请求是只读的,所以即使主库挂了,它们也可以继续从主库上读取。

此外,我们低优先级请求与高优先级请求也进行了区分,对于那些高优先级的请求,OpenAI 分配了专用的只读从库,避免它们被低优先级的请求影响

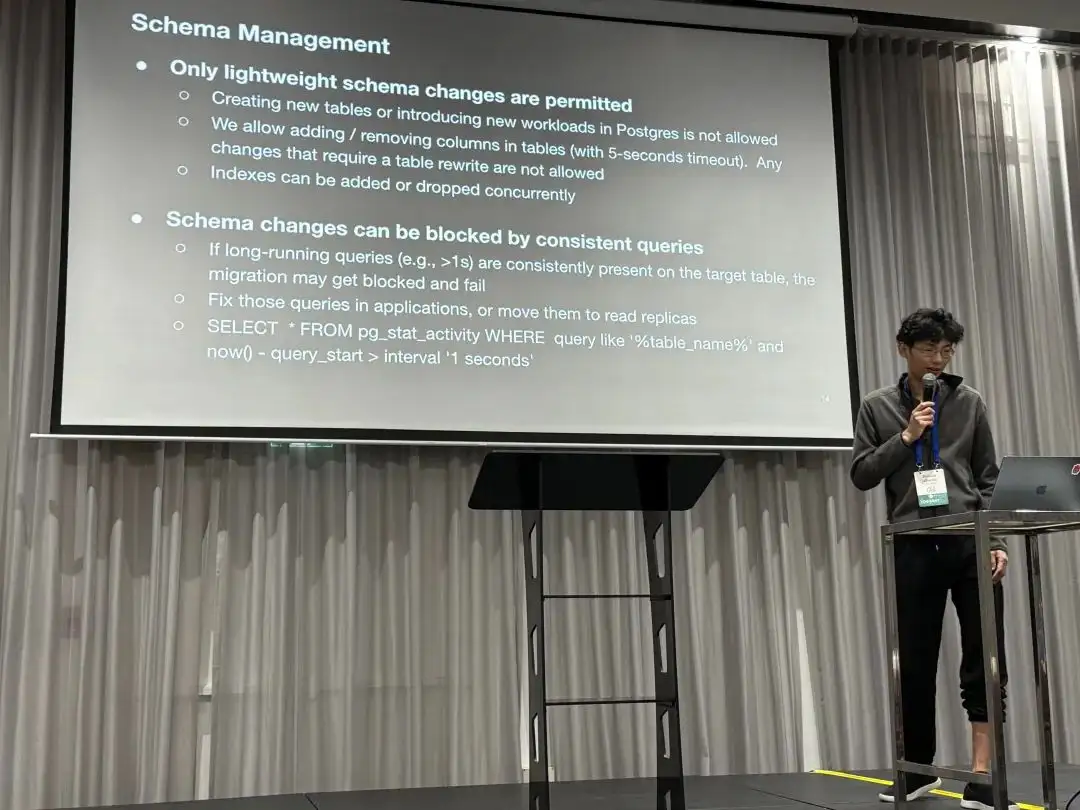

模式管理

第四项是只允许在此集群上进行轻量的模式变更。这意味着:

- 新建表,或者把新的负载丢上来是不允许的

- 可以新增或移除列(设置5秒超时),任何需要重写全表的操作都是不允许的。

- 可以创建/移除索引,但必须使用

CONTURRENTLY。

另一个提及的问题是运行中持续出现的长查询(>1s)会一直阻塞模式变更,最终导致模式变更失败。解决这个问题的措施是让应用把这些慢查询优化掉或者移到只读从库上去。

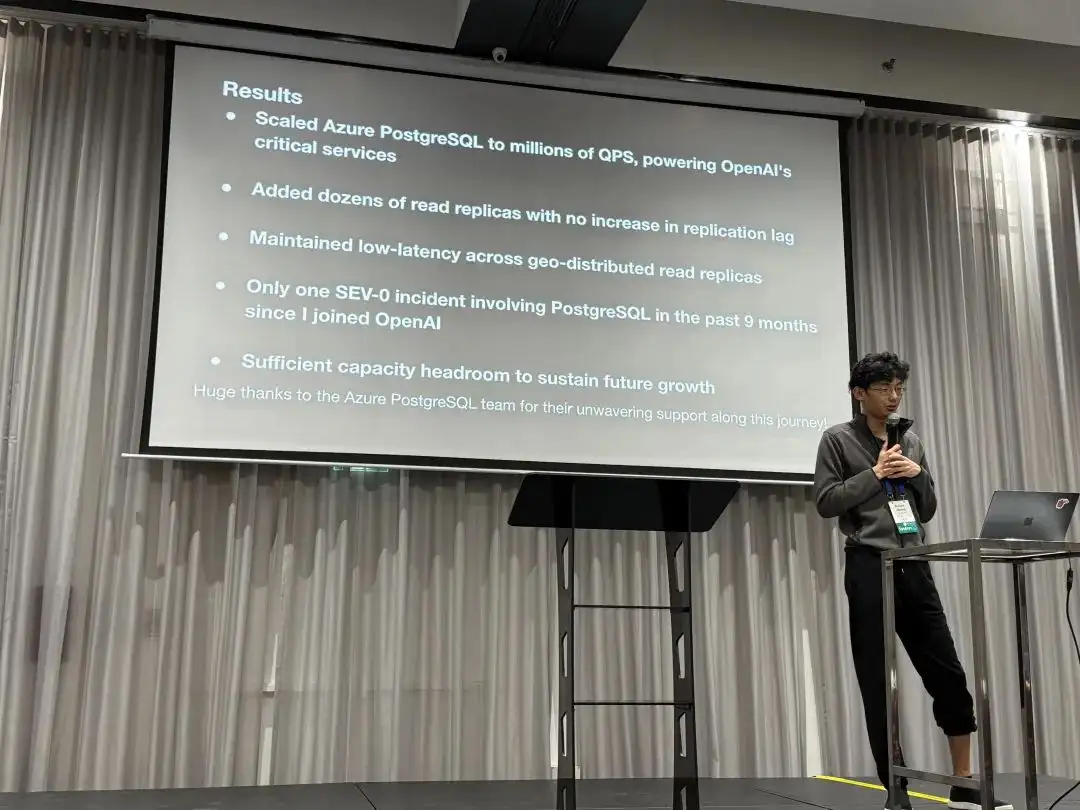

结果

- 将 Azure 上的 PostgreSQL 伸缩至百万 QPS,支撑了 OpenAI 的关键服务

- 在不增加复制延迟的前提下新增了几十个从库(不到 50)

- 将只读从库部署至不同的地理区域并保持低延迟

- 过去9个月内只有一起与 PostgreSQL 有关的零级事故•仍然为未来增长保留了足够的空间

“在 OpenAI,我们在使用一写多读的未分片架构,证明了 PostgreSQL 在海量读负载下也可以伸缩自如”

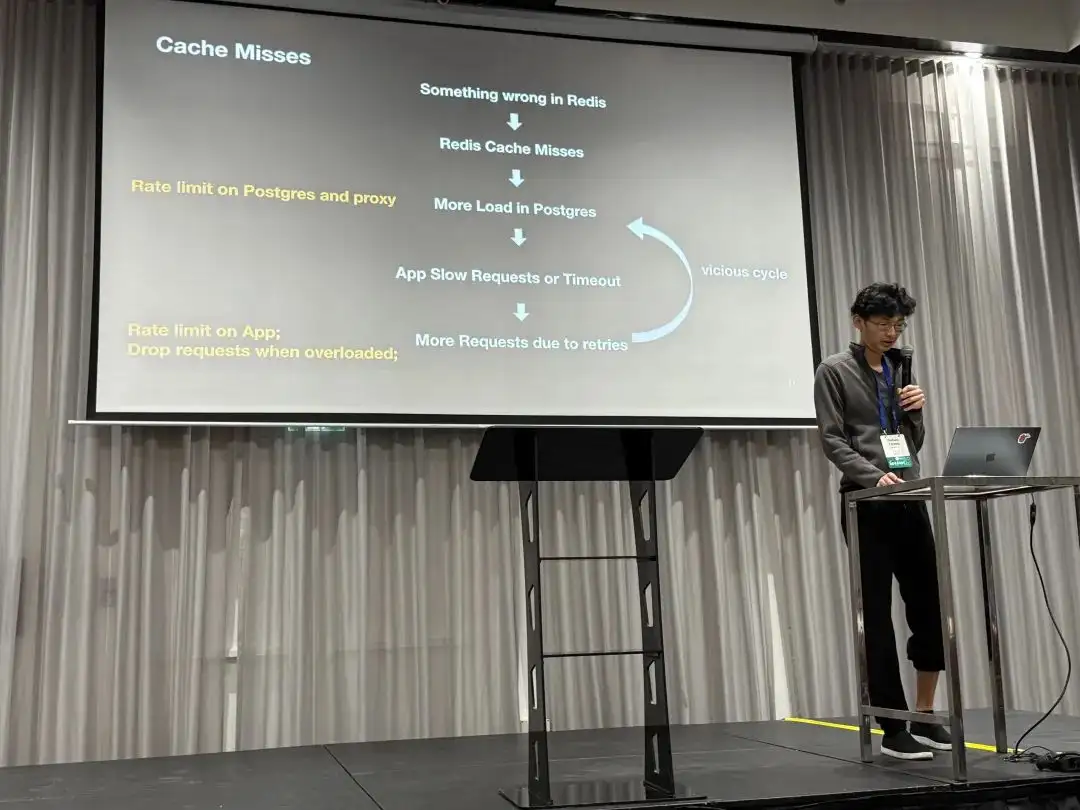

故障案例

此外,OpenAI 还分享了几个问题案例研究,第一个案例是缓存故障导致的雪崩。

第二个故障比较有趣,是极高 CPU 使用率下触发了一个 BUG。导致即使 CPU 水位恢复,WALSender 也一直在自旋循环而不是干正事发送 WAL 日志给从库,从而导致复制延迟增大。

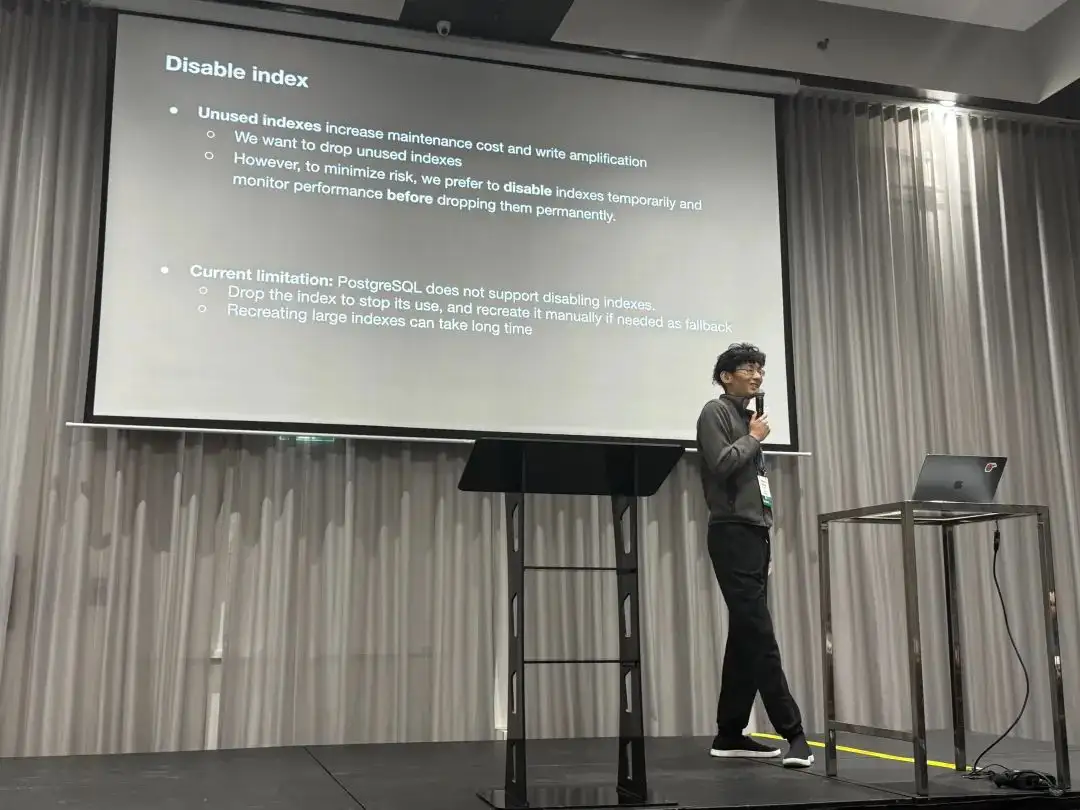

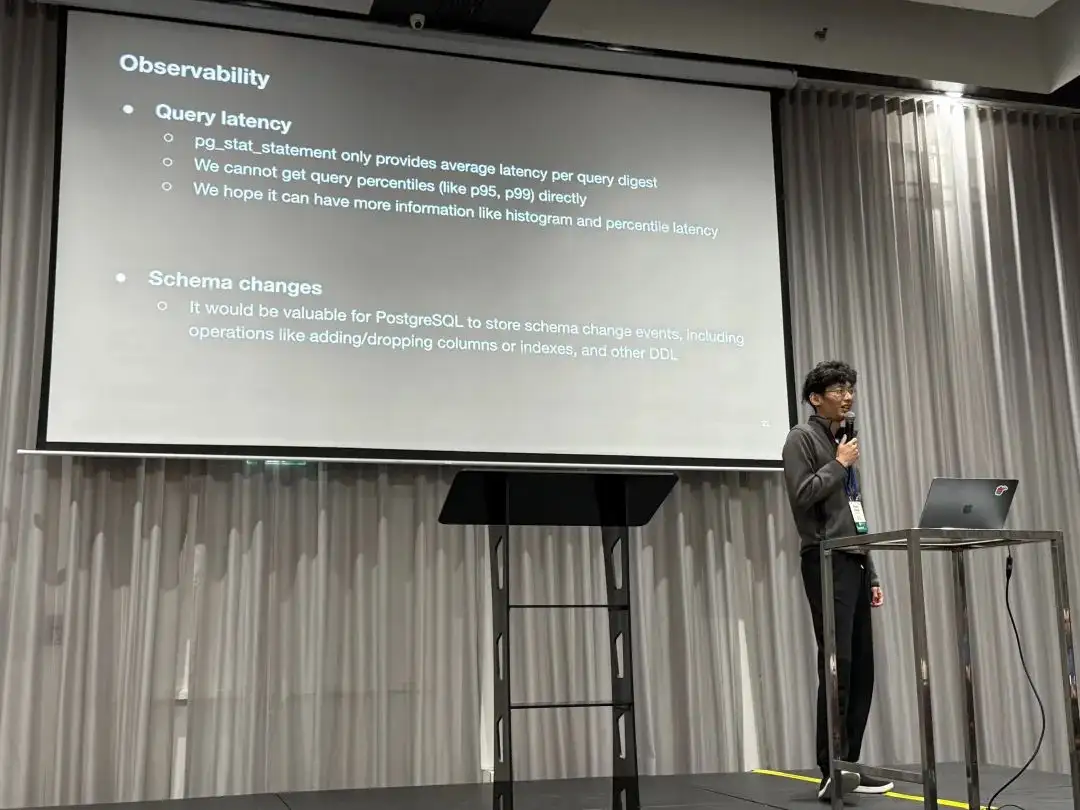

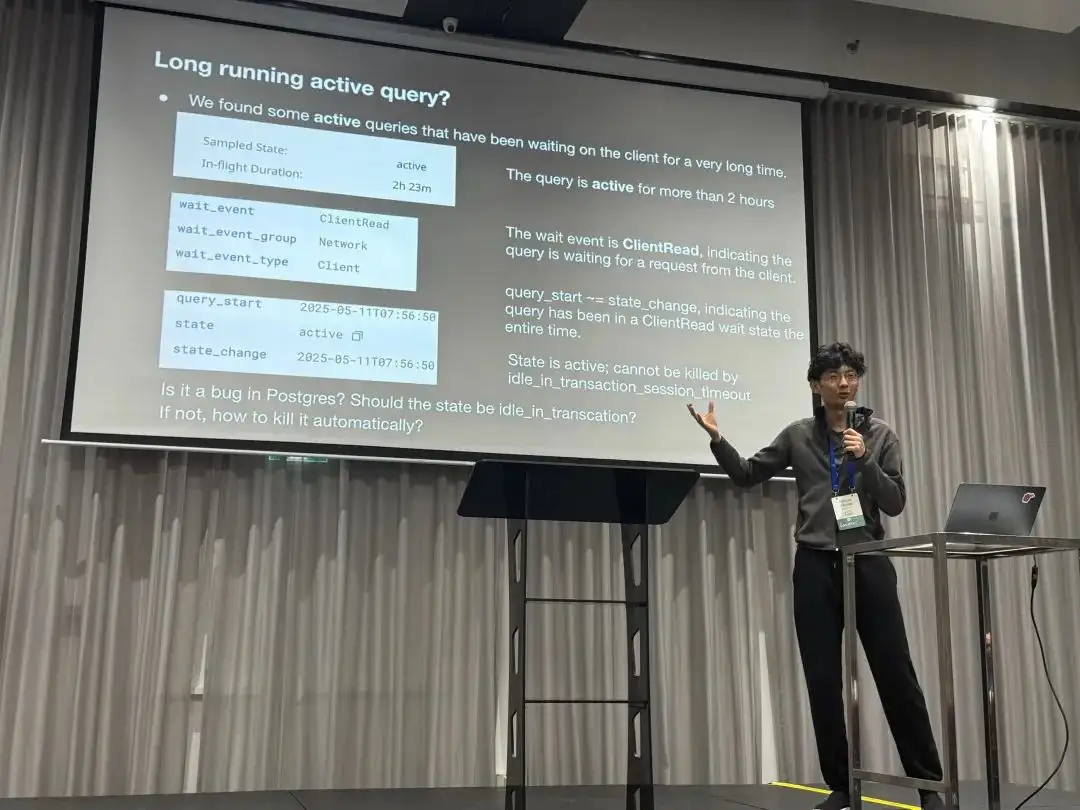

功能需求

最后,Bohan 也向 PostgreSQL 开发者社区提出了一些问题与特性建议:

第一个是关于禁用索引问题的,不用打索引会导致写放大与额外的维护开销,他们希望移除没用的索引,然而为了最小化风险, 他们希望有一个 “Disable” 索引的特性,并监控性能指标确保没问题后再真正移除索引。

第二个是关于可观测性的,目前的 pg_stat_statement 只提供每类查询的平均响应时间,

而没法直接获得 (p95, p99)延迟指标。他们希望拥有更多类似 histogram 与 percentile 延迟的指标。

第三项是关于模式变更的,他们希望 PostgreSQL 可以记录模式变更事件的历史,例如新增/移除列,以及其他 DDL操作。

第四个 Case 是关于监控视图语义的。他们发现了一条会话 State = Active,WaitEvent = ClientRead 持续了两个多小时。 也就是有一条链接 QueryStart 之后一直 Active 了很长时间,而这样的链接就没有办法被 idle in transaction 超时给杀掉,希望了解这是一个 Bug 吗,以及如何解决。

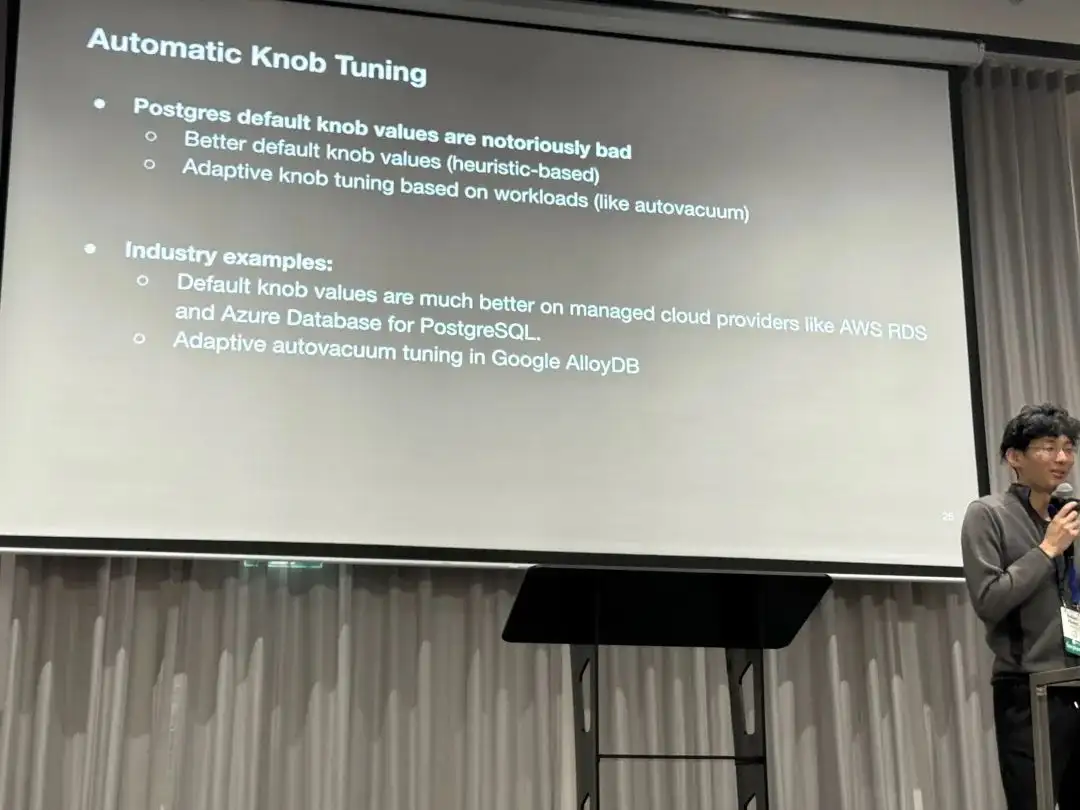

最后是关于 PostgreSQL 默认参数的优化建议,PostgreSQL 默认参数值过于保守了。 是否可以使用一些更好的默认值,或者使用启发式的设置规则?

老冯评论

尽管 PGConf.Dev 2025 主要关注的是开发,但也经常可以看到一些用户侧的 Use Case 分享。 比如这次 OpenAI 的 PostgreSQL 伸缩实践。其实这类主题对于内核开发者来说还是很有趣的, 因为很多内核开发者确实对极端场景下的 PostgreSQL 用例没有概念,而这类分享会很有帮助。

老冯从 2017 年底在探探管理着几十套 PostgreSQL 集群,算是国内互联网场景下最大最复杂的部署之一: 几十套 PG,250 万左右的 QPS。那时候我们最大的核心主库一主 33 从,一套集群承载了 40万左右的 QPS。 瓶颈也卡在了单库写入上,最后进行了分库分表,使用类 Instagram 的应用侧 Sharding 解决了这个问题。

可以说,OpenAI 在这次分享中遇到的问题,以及采取的解决手段,我都曾经遇到过。 当然不同的是当下的顶级硬件可要比八年前牛逼太多了,让 OpenAI 这样的创业公司可以用一套 PostgreSQL 集群,在不分片,不Sharding 的情况下直接服务整个业务。 这无疑为《分布式数据库是个伪需求》提供了又一记强有力的例证。

在聊天提问的时候,老冯了解到 OpenAI 使用的是 Azure 上的托管 PostgreSQL,使用最高可用规格的服务器硬件,从库数量达到 40+,包括一些异地副本, 这套巨无霸集群总的读写 QPS 为 100 万左右。监控使用 Datadog,业务从 Kubernetes 中通过业务侧的 pgbouncer 链接池化之后访问 RDS 集群。

因为是战略级甲方,Azure PostgreSQL Team 提供贴心服务。但显然,即使是使用了顶级的云数据库服务,也需要客户在应用/运维侧有足够的认知与水平 —— 即使有 OpenAI 这样的智力储备,也依然会在 PostgreSQL 的一些实践驾驶案例中翻车。

会议结束后晚上的 Social 环节,老冯和 Bohan 还有两位数据库 Founder 一起唠嗑唠到了凌晨,相谈甚欢。非公开的讨论十分精彩,不过老冯无法就此透露更多,哈哈。

老冯答疑

关于 Bohan 提出的几个问题与特性建议,老冯倒是可以在这里做一个解答。

其实大部分 OpenAI 想要的功能特性需求 PostgreSQL 生态中已经有了,只不过不一定在原生 PG 内核与云数据库环境中可用。

关于禁用索引

PostgreSQL 其实是有禁用索引的“功能”,只需要更新 pg_index 系统表中的 indisvalid 字段为 false,

这个索引就不会被 Planner 使用,但仍然会在 DML 中被继续维护。从原理上讲这没什么毛病,因为并发创建索引就是利用这两个标记位(isready, isvalid)来实现的,并不算什么黑魔法。

但 OpenAI 无法使用这种方式,我可以理解这里的原因:这是一个未被文档记录的 “内部细节” 而非正式特性,但更重要的原因是云数据库通常不提供 Superuser 权限,所以没办法这样更新系统目录。

但回到最原始的需求 —— 害怕误删索引,这个问题有更简单的解决办法,直接从监控视图中确认索引在主从上都没有访问即可。你只要知道了很长时间都没人用这个索引,就可以放心删除它。

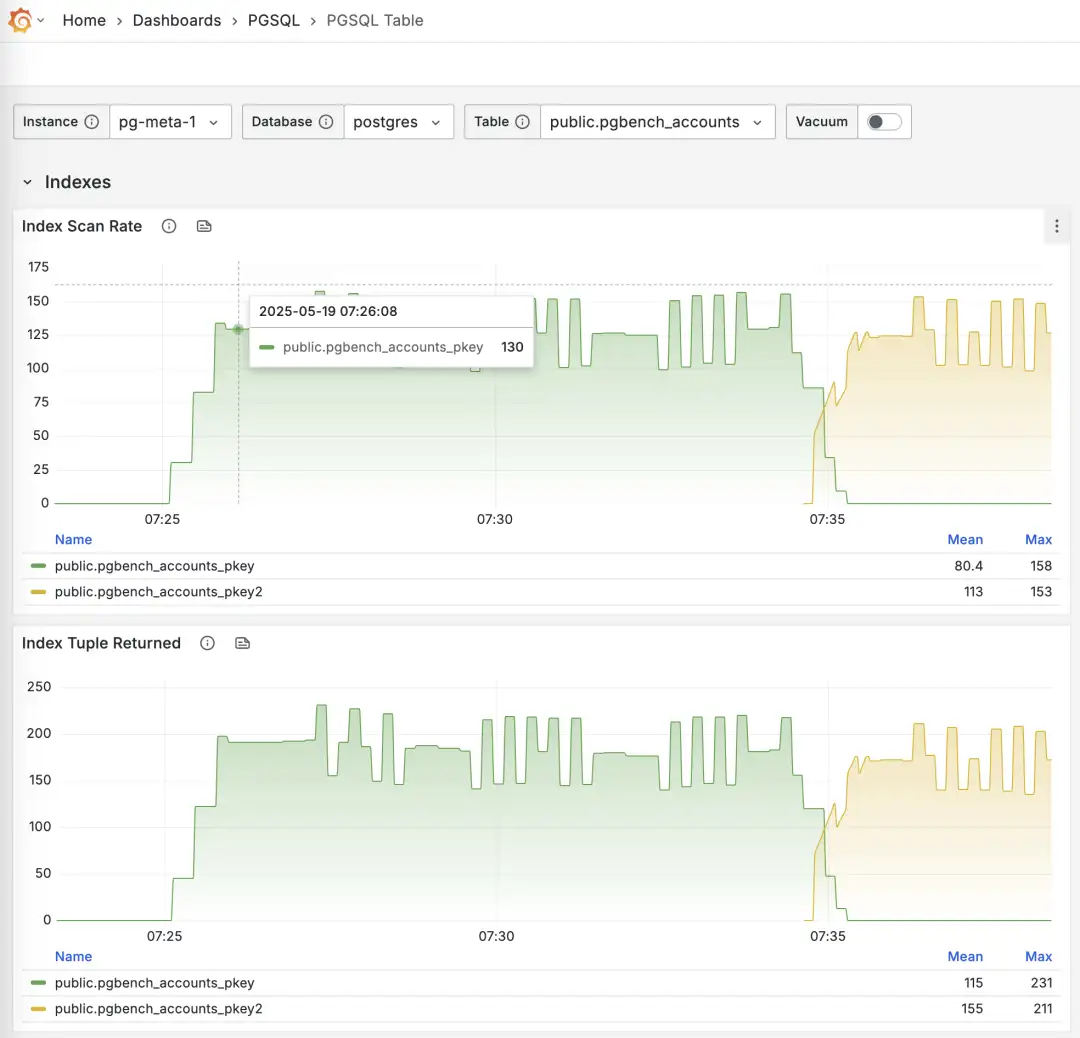

使用 Pigsty 监控系统 PGSQL TABLES 查阅在线切换索引的过程

-- 创建一个新索引

CREATE UNIQUE INDEX CONCURRENTLY pgbench_accounts_pkey2 ON pgbench_accounts USING BTREE(aid);

-- 标记原索引为无效(不使用),但继续维护,Planner 将自动使用其他索引替代

UPDATE pg_index SET indisvalid = false WHERE indexrelid = 'pgbench_accounts_pkey'::regclass;

关于可观测性

其实 pg_stat_statements 提供了均值与标准差,可以使用正态分布的性质来估算出分位点指标。

但这只能作为模糊的参考,而且需要定时重置计数器,否则全量历史统计值的效果会越来越差。

PGSS 在短期内可能并不会提供 P95, P99 RT 这样的百分位点指标,因为这会导致这个扩展所需的内存翻个几十倍 —— 对于现代服务器来说这倒也不算什么,但对于一些极端保守的场景就会有问题。我在 Unconference 上问了 PGSS 的维护者这个问题,短期内可能并不会发生。 我也问了 Pgbouncer 的维护者 Jelte 是否可能在链接池层面解决这个问题,短期内也不会有这样的特性出现。

然而这个问题其实也是有其他解法的,首先 pg_stat_monitor 这个扩展就明确提供了详细的分位点 RT 指标,可以解决这个问题,但也要考虑分位点指标采集对集群性能造成的影响。

通用,无侵入,且无数据库性能损耗的办法,是在应用层面 DAL 直接添加查询 RT 监控,但这需要应用端的配合与努力。

此外,使用 ebpf 旁路采集 RT 指标是一个很棒的想法,不过考虑到他们用的 Azure 托管 PostgreSQL,不会给服务器权限,所以这条路可能被堵死了。

关于模式变更记录

其实 PostgreSQL 的日志已经提供这个选项了,只要把 log_statement

设置为 ddl (或更高级的 mod, all),所有 DDL 日志就会保留下来。扩展插件 pgaudit 也提供了类似的功能。

但我猜他们想要的不是这种 DDL 日志,而是类似提供一个可以通过 SQL 查询的系统视图。所以另一种选项是 CREATE EVENT TRIGGER ,

使用事件触发器直接在数据表中记录 DDL 事件即可。扩展 pg_ddl_historization 提供了更简便的记录方式,我也编译打包了这个扩展。

创建事件触发器也需要 superuser 权限,AWS RDS 有一些特殊处理可以使用这个功能,不过 Azure 上的 PostgreSQL 似乎就不支持了。

关于监控视图语义

在 OpenAI 的这个例子中,pg_stat_activity.state = Active 意味着后端进程依然在同一条 SQL 语句的生命周期里,WaitEvent = ClientWait 意味着进程在CPU上等客户端的数据过来。

两者同时出现,典型的例子就是 COPY FROM STDIN 空等,但也可能是 TCP 阻塞,或者卡在 BIND / EXECUTE 中间。所以也不好说就是 BUG,还是要看链接具体在做什么。

有人认为,等待 Client I/O ,这从 CPU 角度来看这不应该是 “空闲” (Idle) 状态吗?但 State 关注的是语句本身的执行状态,而不是 CPU 的忙闲与否。

State = Active 意味着 PostgreSQL 后端进程认为 “这条语句尚未结束”。行锁、buffer pin、快照、文件句柄等资源就被视为“正在使用”,这并不代表它正在 CPU 上运行,

当该进程在 CPU 上运行,在 For 循环中等待客户端数据的到来时,等待事件为 ClientRead,而当它让出 CPU 在后台等待时,等待事件为 NULL。

当然回到这个问题本身,其实是有别的解决办法的。例如在 Pigsty 中,当通过 HAProxy 访问 PostgreSQL 时, 我们会在 LB 层面为 Primary 服务设置一个 链接超时,默认为 24h ,更高标准的环境会更短,比如 1h。 那么就意味着超过1小时的链接就会被挂断。当然,这个也需要在应用侧的链接池相应配置最大生命周期,尽可能主动挂断而不是被挂断。 对于离线只读服务则可以不设置这个参数,来允许那种跑两三天的超长查询。这样就可以为这种 Active 但等待 I/O 的情况提供兜底。

但我也怀疑在 Azure PostgreSQL 是否提供了这种控制的可能性。

关于默认参数

PostgreSQL 的默认参数相当保守,例如 默认使用 128 MB 内存(最小可以设置 128 KB !) 从好的方面讲这让他的默认配置能在几乎所有环境中都能跑起来。从坏的方面讲我真的见过 1TB 物理内存使用 128 MB 默认配置运行的案例……(因为双缓冲,竟然还真跑了很久生产业务)。

但总体来说,我觉得默认参数保守点不是坏事,这个问题可以在更灵活的动态配置过程中解决。

RDS 和 Pigsty 都提供了足够好的 初始参数启发式配置规则,充分解决这个问题了。

但这个特性确实可以加入到 PG 命令行工具中,比如在 initdb 时自动检测 CPU/内存数量,磁盘大小与介质并相应设置优化的参数值。

自建 PostgreSQL ?

OpenAI 提出的几个问题,挑战其实并不是来自 PostgreSQL 本身,而是来自托管云服务的额外限制。 一种解决办法就是利用 Azure 或其他资源云的 IaaS 层,使用本地 NVMe SSD 实例存储自建 PostgreSQL 集群以绕开限制。

实际上,老冯的 Pigsty 就是为了解决类似规模下 PostgreSQL 挑战而给自己做的云数据库解决方案。 It scales well ,支撑起了探探 25K vCPU 的 PostgreSQL 集群与 2.5 M QPS。 包括上面这些问题,甚至是许多 OpenAI 还没有遇到的问题也都有了解决方案,并做到了 Pigsty 中,并开源免费,开箱即用。

如果 OpenAI 感兴趣,我当然乐意提供一些支持,不过我觉得狂飙增长的时候,折腾数据库 Infra 可能并非高优先级的事项。 好在,他们还是有着非常优秀的 PostgreSQL DBA,能够继续探索出这些道路来。

Etcd 坑了多少公司?

前几天 影视飓风分享的 Pigsty / PostgreSQL 高可用案例 里面踩的一个雷在 X 上引起网友热议。 “因为 etcd 未开启自动压实功能,且默认仅为 2GB 容量”,ayanamist 评论到:“我倒要看看 etcd 这个傻逼 2G 的设计可以坑多少公司”。

etcd 的 slogan 是:“一个分布式的、可靠的键-值存储,用于存放系统中最为关键的配置数据”。 目前最常见的场景是用于存储 K8S 的元数据。当然类似 Patroni 这样的 PostgreSQL 高可用方案也可能会用到 etcd 作为 DCS。

在 Ayanamist 这条推的评论下,可以看到许多人都踩过这个雷。大部分是 K8S 用户,也有在 PG 高可用场景上翻车的例子。

etcd 的缺陷

ETCD 有一个非常傻逼的设计,就是在默认配置下,写满 2GB 数据就挂了。

具体来说,etcd 每次写入都会创建一个新的版本,当这些数据/版本超过 2GB 之后,etcd 就会进入维护模式(挂了)。 想象一个没有启用 GC 垃圾回收的 Java JDK,就可以理解 etcd 有多坑了。

当然,其实是有参数配置项可以解决这个问题的,例如使用以下配置项,可以让 etcd 只保留最近 24 小时的版本,从而避免了存储空间的无限增长。

auto-compaction-retention: "24h"

但坑就坑在,这并不是一个默认配置,这个参数的默认值是 0,也就是保留所有历史版本。

更坑的是,在 etcd “维护” 部分的文档里的语句很有误导性,例如在 Maintenance 部分是这么说的:

为了保持稳定性,etcd 集群需要定期维护。根据 etcd 应用的需求,这些维护通常可以自动化执行,且不会导致停机或显著性能下降。

而且在下面的 “Auto Compaction” 部分,一眼看过去,给人的感觉就是 auto compact 设置了很好的默认值嘛: 每小时垃圾回收一次,保留10个小时,这不是挺好的?应该不需要我操心了。

但如果你没去看那个 Configuration Options 参考文档,那完犊子了

最后,这个问题还不会在 etcd 开始服务时立即暴露,而是会在使用几个月之后突然爆雷。

PostgreSQL 的例子

其实在很早的时候(8.0, 2005 年前) PostgreSQL 也有这个问题。 PostgreSQL 使用与 etcd 类似的 MVCC 逻辑,每次写入也都是创建新版本/标记删除,所以会留下许多历史版本。 当垃圾版本积累的太多而没有清理时,数据库就炸了,而这个操作是需要管理员手工执行的,所以成为了 PG 广为诟病的一个问题。

不过后来 PostgreSQL 引入了 AutoVacuum 机制,也就是自动垃圾回收,会有守护进程不断扫描清理回收,免去了人工操作的烦恼。 因此在现代硬件上,默认参数下的 PostgreSQL 基本不会再因为这个问题而头疼了。

然而,并非所有数据库都像 PostgreSQL 这样 “靠谱贴心”,给用户设置了足够好的 “默认值”,可以开箱即用。etcd 就是一个非常典型的例子。

Pigsty 的例子

Pigsty 也在这个问题上翻过车。从 2023-02-28 发布的 v2.0.0 首次引入 etcd 作为 DCS 开始,到 2024-02-13 v2.6.0 修复 etcd 的这个问题, 整整一年的版本都受到 etcd 这个问题的影响。我们在文档的 漏洞缺陷 与 ETCD FAQ 中多次强调过这个问题。

在这里还是要特别提醒一下使用 Pigsty v2.0 ~ v2.5 的用户,请尽快更新升级一下 Etcd 的配置。

AI时代,软件从数据库开始

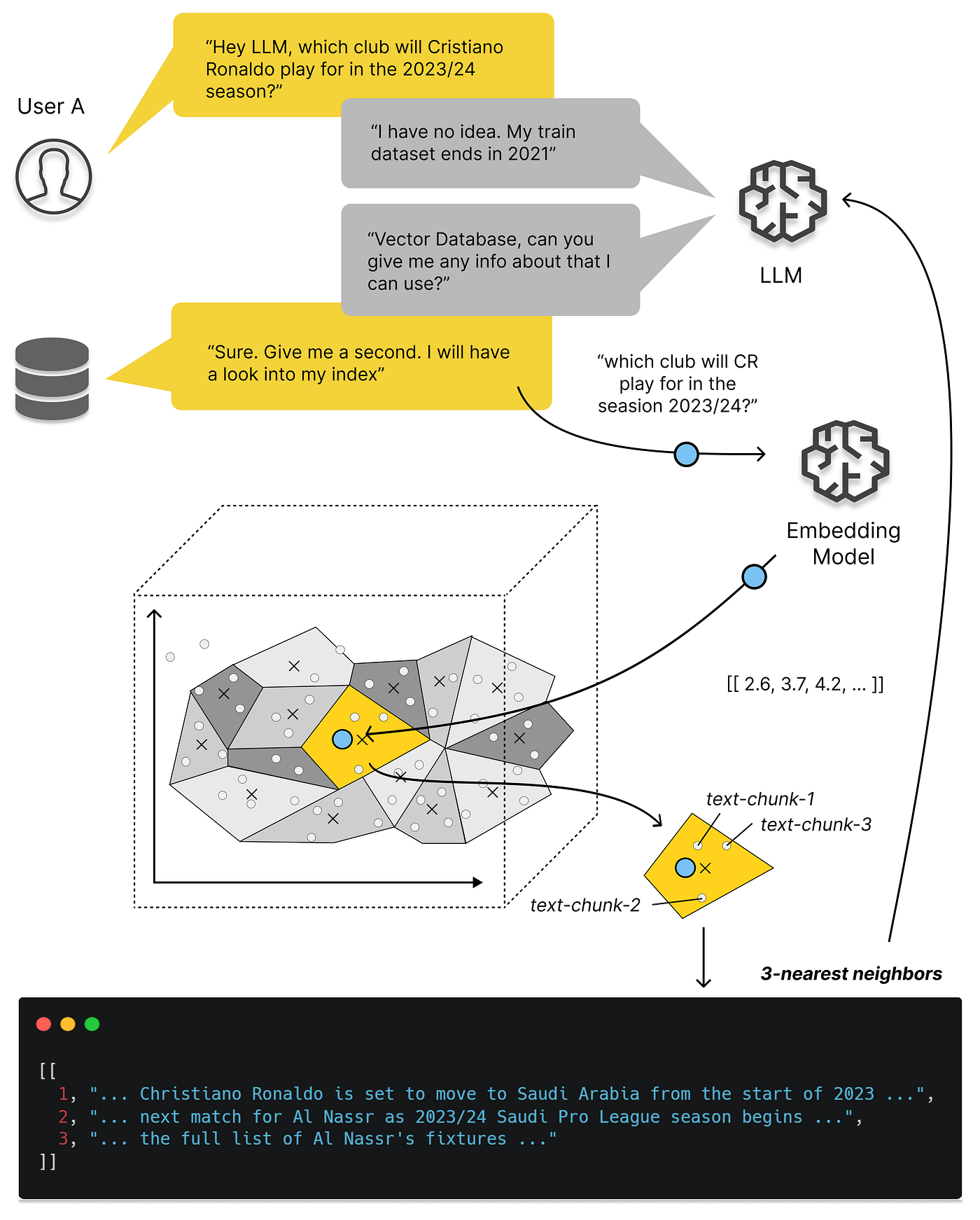

未来的软件形态是 Agent + 数据库。没有前后端中间商,Agent直接CRUD。数据库技能相当保值,而 PostgreSQL 会成为 Agent 时代的数据库。

SaaS已死?软件从数据库开始

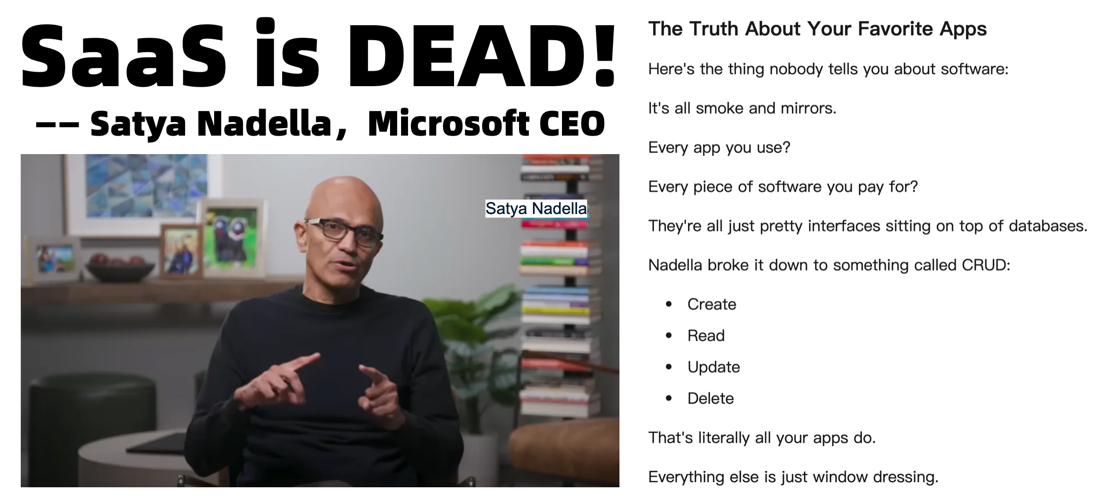

AI行业近年大爆发,生成式模型席卷各个领域,仿佛不谈AI就落伍了。然而软件的世界终究是从数据库开始的。微软 CEO 纳德拉在公开访谈中表示:在 Agent 时代,SaaS is Dead,而未来的软件形式将是 Agent + Database 。

“…I think, the notion that SaaS business applications exist, that’s probably where they’ll all collapse, right in the Agent era…”

— Satya Nadella https://medium.com/@iamdavidchan/did-satya-nadelle-really-say-saas-is-dead-fa064f3d65d1

“对于 SaaS 应用,也就是各类企业软件,这确实是个至关重要的问题。进入 Agent 时代之后,传统‘业务应用’这一层大概率会被压缩乃至消解。 为什么?本质上,这些应用就是一张 CRUD 数据库外加一堆业务逻辑。 而这些业务逻辑今后都会迁移到智能 Agent 中 —— 这些 Agent 能跨多库 CRUD,不会在意底层是什么后台,想改哪张表就改哪张表。 逻辑一旦全部上移到 AI 层,人们自然就会开始替掉后端,对吧?”

这个观点一出,业界一片哗然:难道几十年来我们习以为常的软件中间层要被挤掉,只剩智能 Agent 直接对话数据库了吗?如果你使用过一些 Vibe Coding,或者 MCP 桌面端,就能理解纳德拉想说什么。 你可以在 Claude / Cursor 中直接通过对话来访问像 PostgreSQL 这样的数据库。让 AI 根据你的问题,生成查询,处理并整合结果。在一些比较简单分析场景中,它的表现已经超出我的预期了。

在未来,当所有应用的逻辑都移动到 AI Agent 层后,能坚挺地留在后端撑场子的,也就是数据库了。 今天,老冯就来和大家聊聊,为什么在AI浪潮下数据库依然是那个“定海神针”,同时也探讨AI时代软件开发哪些技能会贬值、哪些依然保值,并展望 Agent 时代,哪些数据库能够笑到最后。

Agent + DB:AI时代中间商消失

曾几何时,我们习惯了在应用里点点点,然后后台服务器去查询数据库、执行逻辑,再把结果返回前端给我们看。在这个过程中,应用本身其实是用户和数据库之间的“中间商”。但在AI时代,这个中间商正面临失业危机——智能代理可以直接跟数据库对话,把中间那层壳子拿掉。

想象一个生动的例子:订机票。传统流程是用户打开订票网站或App,填写日期地点,前端把请求发给后端,后端调用数据库或第三方API查航班,再把结果包装成网页返回给你。在整个过程中,浏览器或者 APP充当了中介。然而在Agent+Database的新形态下,你也许只需要对着你的AI助手说:“帮我订下周一去东京的最便宜的直飞航班,靠窗座,谢谢!”

接下来像魔法的事情发生了:这个AI Agent 会自动去几个航空公司的数据库或接口抓取航班数据,比价筛选,直接在数据库里下单锁座,然后给你回复:“搞定啦,电子机票已发邮箱。” 整个过程几乎没有传统意义上的前端界面—— AI Agent 本身就是界面,它替你完成了以前由多个软件系统串联才能完成的工作。

当然,符合大部分用户想像的 AI Agent 可能是那种 RPA Computer Use Agent,就是 AI 替你去移动鼠标敲键盘,通过网站或者 API 去请求服务。但是如果我们考虑理想的终局状态 —— 那些网页界面都是给人用的,机器其实不需要这么麻烦,完全可以绕过所有的前后端,直接操作最核心的东西 —— 数据库。

当然,现实中完全去掉中间层还需要解决安全、权限等诸多问题。不过大方向是高度确定的。应用逻辑越来越多由AI Agent 驱动,数据库则成为这些AI的“原料仓库”和“工作台”。在这个新范式下,数据库不但没被边缘化,反而因为直接面对AI请求而地位特殊。

纳德拉说的正是这种 Agent 直连数据库的终局状态。在 AI 时代,“没有中间商赚差价”不再只是段子,而是可能成为现实:中间应用层被压缩甚至消失,AI直接对接数据库完成任务。Agent 就像全能的小秘书,各家数据库成了它手里的工具箱。听起来很科幻?其实趋势已经很明显了:最近 MCP 爆火不过是 Agent 时代的前奏。

我听陆奇博士说过,比尔·盖茨其实几十年前就已经判断出软件领域的最终形态是 PDA (个人数字助理),当然几十年前受技术条件限制,手持好记星文曲星式的 PDA 肯定离着 AI 数字秘书差着十万八千里。但现在,这个愿景已经完全具备实现的技术条件了。当下爆火的 MCP 不过是 Agent 时代的前夜,而 Google 发布的 ADK,A2A 则可能才刚刚拉开 Agent 时代的序幕。

数据库为什么不会过时?

有人或许担心:AI都这么智能了,会不会有一天不需要传统数据库,让 AI 直接生成就行?这个想法听上去很酷,但实际情况是模糊智能系统无法取代精确的数据库系统,原因有很多:

1. 模糊系统 vs 精确系统: 大型语言模型本质上是概率模型,擅长处理不确定性和模糊问题,但让它们记住精确事实可不容易。在这一点上,它跟人类有着一样的缺陷 —— 都是模糊系统。人脑再好使,问题复杂了也需要求诸于计算器,Excel,数据库等 精确工具。无论AI多聪明,它要给出靠谱的结果,背后还是得有准确的数据支持,而数据库擅长的正是精确存储和检索。AI生成一段文本可以有点小误差无伤大雅,但要是涉及订单数量、财务报表这些严肃数据,一丝偏差都可能酿成大祸,这时候还是得靠传统数据库的精确性来保障。模糊AI负责智能推理,精确数据库负责事实基石,两者是互补而非互斥关系。

2. 没有数据库,AI就是无源之水: AI需要海量数据作为原始生产资料,这是显而易见的道理。计算机领域有句老话:“Garbage In, Garbage Out(垃圾进,垃圾出)”,在AI时代依然是真理。如果喂给AI模型的数据源本身质量堪忧,那AI只会加速吐出垃圾结果。这意味着企业越依赖AI决策,就越需要高质量的数据来训练和提供给AI调用。数据从哪儿来?还不是从各种数据库和数据仓库里来!正如业内所强调的:AI系统只能达到其所用数据的水准。因此,数据库作为数据的载体和提供者地位不降反升。哪怕未来最先进的AI代理,上线第一天也得先连接上你的数据库取数,否则就是个巧妇难为无米之炊的空架子。

3. 信息的可靠存储与可信度: 人类社会早就明白保存信息的价值。尽管人类可以“口耳相传”,但记忆容量有限,传承会模糊走样。从商周铸鼎刻字、甲骨铭文,到史官笔录春秋,再到印刷术和现代的图书馆档案室,我们一直在追求更可靠、更长久的存储方式。数据库正是信息社会的“鼎”和“史册”。它承担着记录和保管的重要职责,是当代的“数字档案库”。LLM 可以用有损压缩的方式模糊记住主要的知识,但精确保留的原始实时记录依然还需要外部存储。只要人类还重视信息的可靠存储和可信度,数据库的重要性就不会消失。

说到底,问题的关键在于 LLM Agent 替代的是“人”本身,而非人使用的工具。当然肯定有人会问前后端开发也是工具,为什么就数据库这个工具不一样呢?那是因为要解决存储与记忆的问题,无论是人类还是大模型 Agent,都需要使用数据库,这是解决问题的需要面对的本质复杂度。然而本质上来说 LLM/Agent 并不需要这些 给人使用的中间工具 来操作数据库,它本身就拥有这样的能力,这些对 Agent 来说属于无谓的额外复杂度。

当然我们不排除以后会出现一种将数据库直接融入大模型中的新物种(比如沙丘中的人肉计算机“门泰特”,用模糊系统来仿真精确系统),可以直接将数据存储在模型权重中并实时更新,动态调整,让现在的数据库“过时”。但起码对于最近十几年来说,依然是遥远的设想而已。

IT技能:哪些贬值,哪些保值?

我最近重新做了 Pigsty 的官网。整个过程就我一个人,全是我靠嘴来说,Cursor 来脑补,最后摇个 Gemini 2.5 来画图。我想找个前端大手子帮我美化一下,大手子说,我也只能做到这个水平了。他要价 1000 ¥/页面,而我耗时十几分钟靠嘴实现了这样的效果。另一个例子是文档翻译,在三年前,我花了五千块找了个计算机研究生,帮我把三十多份文档从中文翻译成英文。而现在一个翻译工作流,半个小时就能信达雅的将中文内容翻译成各种语言。

AI 带来的生产力提高是非常惊人的,但反过来说,AI 消也灭掉了很多工作岗位,比如翻译,插画师,前端UX 等。你可以说,细分领域 1% 的头部专家永远有饭吃,但 99% 的工作岗位被铲平了,基本上也就意味着这个行业被 AI “替代”掉了。

让许多人震惊的是,AI 最先替代的并不是传统意义上很多人设想的体力劳动或一般性脑力劳动,而是高创造性的领域。例如,创造 AI 的软件工程师/程序员本身就在 AI 时代面临着巨大的冲击。

随着 Anthropic 的 Claude Code Agent 代码泄漏,各种代码 Agent 已经出现了百花齐放。中低级程序员目前已经接近团灭状态,UI / UX 哭晕在厕所,前后端岌岌可危。很多技能在 Vibe Coding 面前快速贬值 —— 几年经验的程序员,被 20 $/月的 AI Agent 打翻在地。不过总的来说,尽管程序员本身受到 Code Agent 的巨大冲击,但好在其他行业还在补数字化的课,程序员作为平均最熟悉 AI 的群体,起码不至于像翻译/插画那样跳崖式塌方。

那么什么 IT 技能最保值呢?在这个剧烈变化的时代中,有一项技能依然稳如老狗,那就是数据库。 AI 行业现状发展瞬息万变,跟之前前端领域有一拼,刚学的新花样很可能过两个月就过时了。反而是几十年前的数据库设计,建模,SQL 等知识在几十年后依然硬朗坚挺。并且按目前的发展势头,还会在 AI 时代继续坚挺下去。未来掌握数据库和数据工程技能的程序员,会更加抢手。而纯粹只会切图写页面、不懂业务数据的人,饭碗可能就危险了。

AI 时代,哪些数据库有机会

那么,哪些数据库值得学习呢?

展望未来数据库江湖,在AI和新应用需求的冲击下,胜出的将是那些满足 Agent 需求的数据库 —— 当然老冯懒得说一些正确而无用的冠冕堂皇屁话 —— 没其他数据库什么事儿了,基本上就是 PostgreSQL 了。

首先,OpenAI 用的是什么?PostgreSQL。然后,Cursor 用的是什么?PostgreSQL,此外,还有 Dify,Notion,Cohere,Replit,Perplexity,你会发现,新一代 AI 公司的数据库选型惊人的一致。Anthropic 虽然没有公开说他们用什么,但是 MCP 的例子里大剌剌摆着 PostgreSQL 作为除了文件系统之外的第二个例子,就很能说明问题了。

而 Cursor 的 CTO Sualeh Asif 在斯坦福 153 Infra @ Scale 上的演讲说的更直接(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4jDQi9P9UIw )

用 Postgres 就行了,别整那些花里胡哨的东西。

大家选择 PostgreSQL 原因很简单, PostgreSQL 可以在一个数据库里解决所有问题:关系型数据,向量数据,JSON文档数据,GIS 地理空间数据,全文检索词向量与倒排索引数据,图数据,甚至还有 OLAP 分析性能比肩 CK 的 DuckDB 列式存储引擎。而这种多模态的能力正是 Agent 复杂多面需求所需要的终极 All-In-One 解决方案:如果你能通过 PG 扩展用一行 SQL 解决千行代码才能解决的问题,那么就可以极大降低 LLM 的心智负担,智力要求与 Token 消耗。

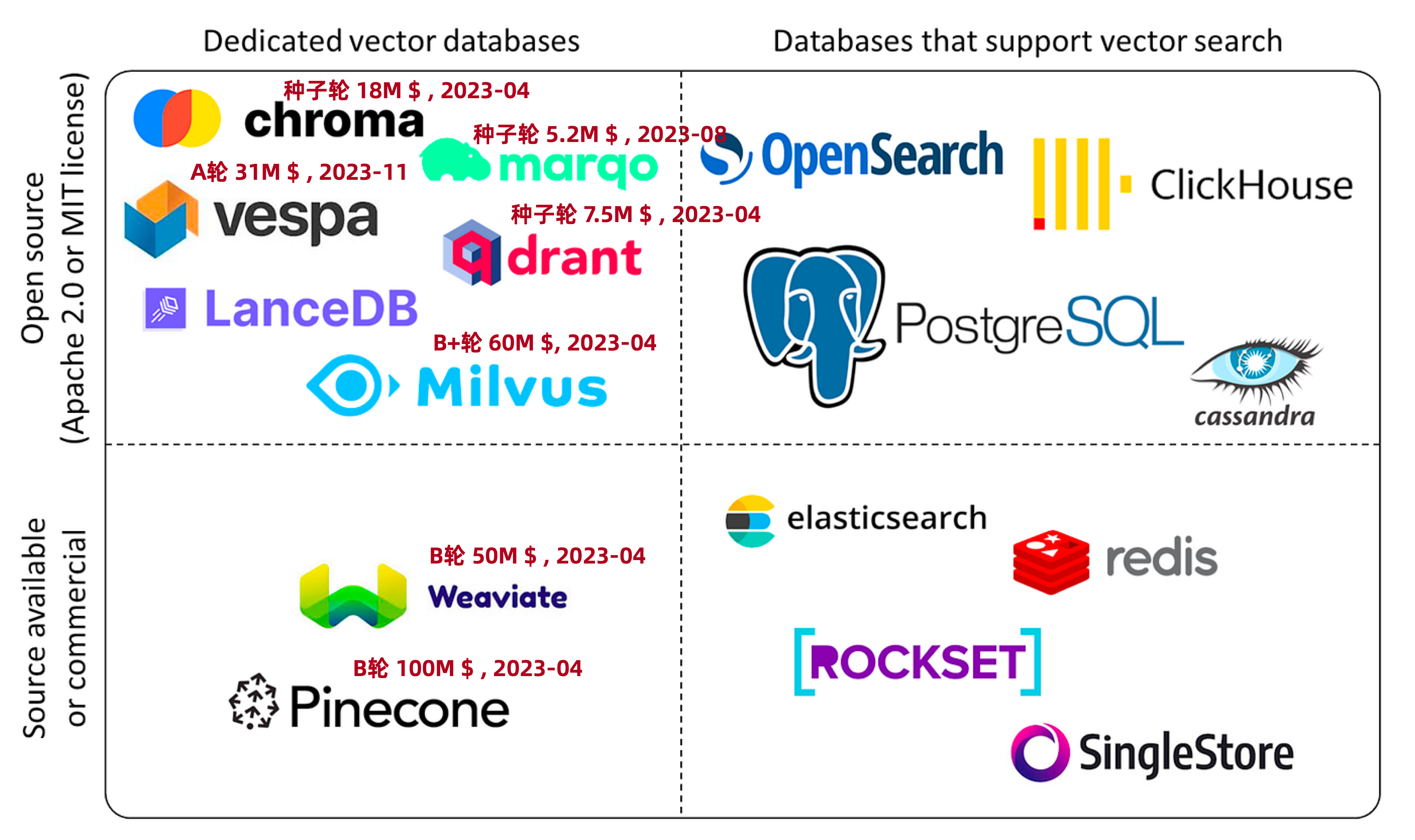

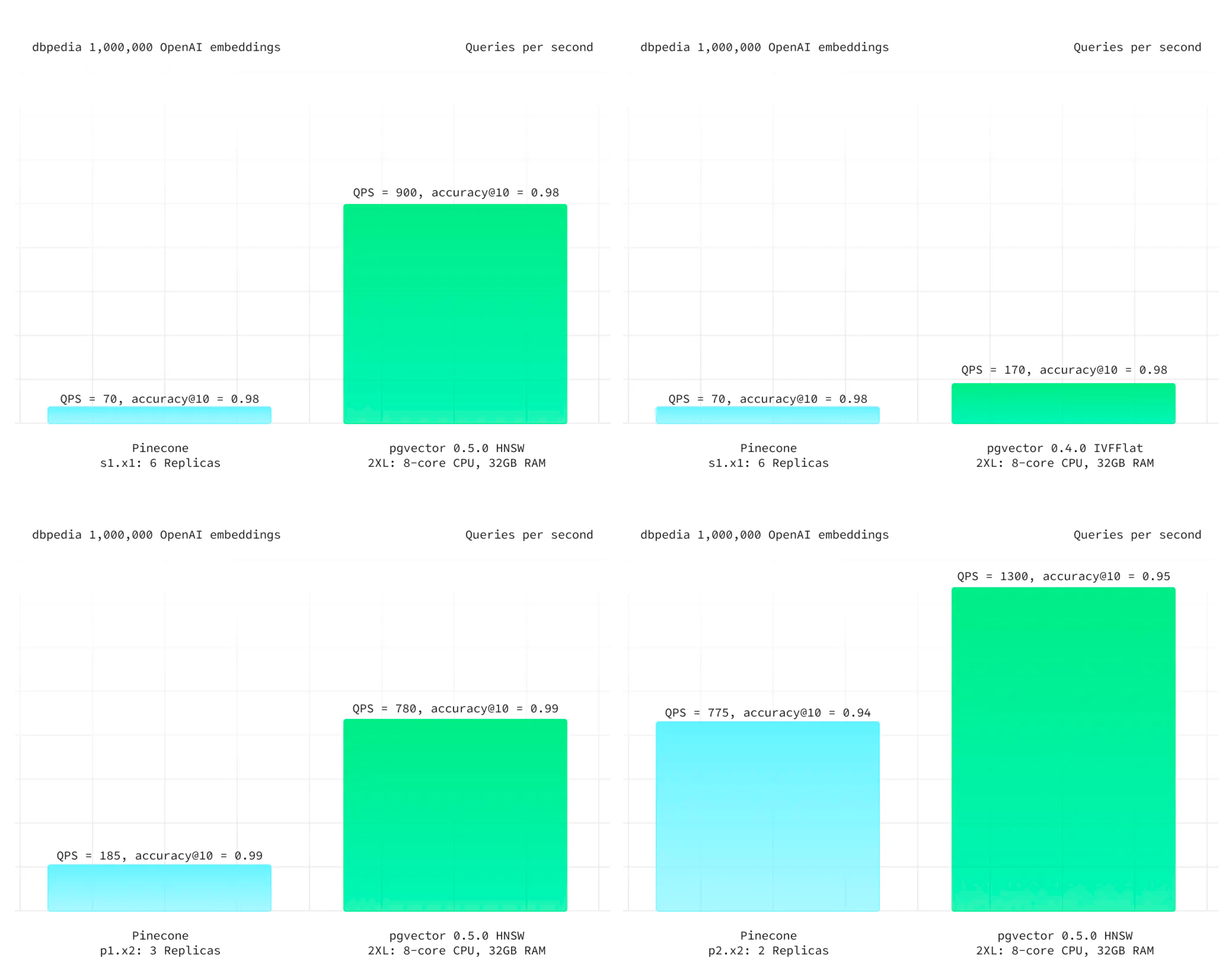

PostgreSQL 生态 + pgvector 俨然成为 LLM-驱动产品的“默认安全牌”。pgvector 在很多人印象里只是 PG 生态中的一个扩展,实际上直到 OpenAI Retrivial Plugin 带火向量数据库赛道之前,这还都属于个人兴趣项目。然而在 PG 社区生态的合力下,例如 AWS ,Neon,Supabase 都砸入了大量资源改进它,让他从六七款 PG 向量扩展中脱颖而出,在一年时间内实现了 150 倍的性能改进,将整个专用向量数据库赛道变成了一个笑话。 —— 即使是专用向量数据库中最能打的 Milvus,也无法撼动这一点:它不是在跟某个 PG 社区爱好者打擂台,而是跟 AWS RDS 团队和好几个精英团队在拼资源 … )

当然,我认为 SQLite 也会在 Agent 时代进一步大放光彩,当然 PG 生态也有 PGLite/DuckDB 来这个领域竞争。

当然最后是老冯的广告时 间。PostgreSQL 是个好数据库,但想用好这个数据库其实并不容易。无论是天价的 RDS 还是稀缺的 DBA,对许多用户都不是一个可选项。但比起手工土法自建来说,我们提供了一个开源免费的更好选择:开箱即用的 PostgreSQL 发行版 Pigsty,打包了 PG 生态所有能打的扩展插件(当然 pgvector 必须默认安装),让你一分钟,几条命令就从一台裸服务器上拉起生产级的 PostgreSQL RDS 服务。如果你需要专家的服务支持,我们提供可以摇人兜底的付费订阅选项~:但软件本身是开源免费不要钱的,纯属做做公益,交个朋友,希望能够帮助大家用好 PostgreSQL。

MySQL vs PostgreSQL @ 2025

在 2025 年的当下,MySQL 无论是在功能特性集,质量正确性,性能表现,还是生态与社区上都被 PostgreSQL 拉开了差距,而且这个差距还在进一步扩大中。

今天我们就来对 MySQL 与 PostgreSQL 进行一个全方位的对比,从功能,性能,质量,生态来全方位反映这几年的生态变化。

功能

让我们先从开发者最关注的东西 —— 功能特性开始说起。

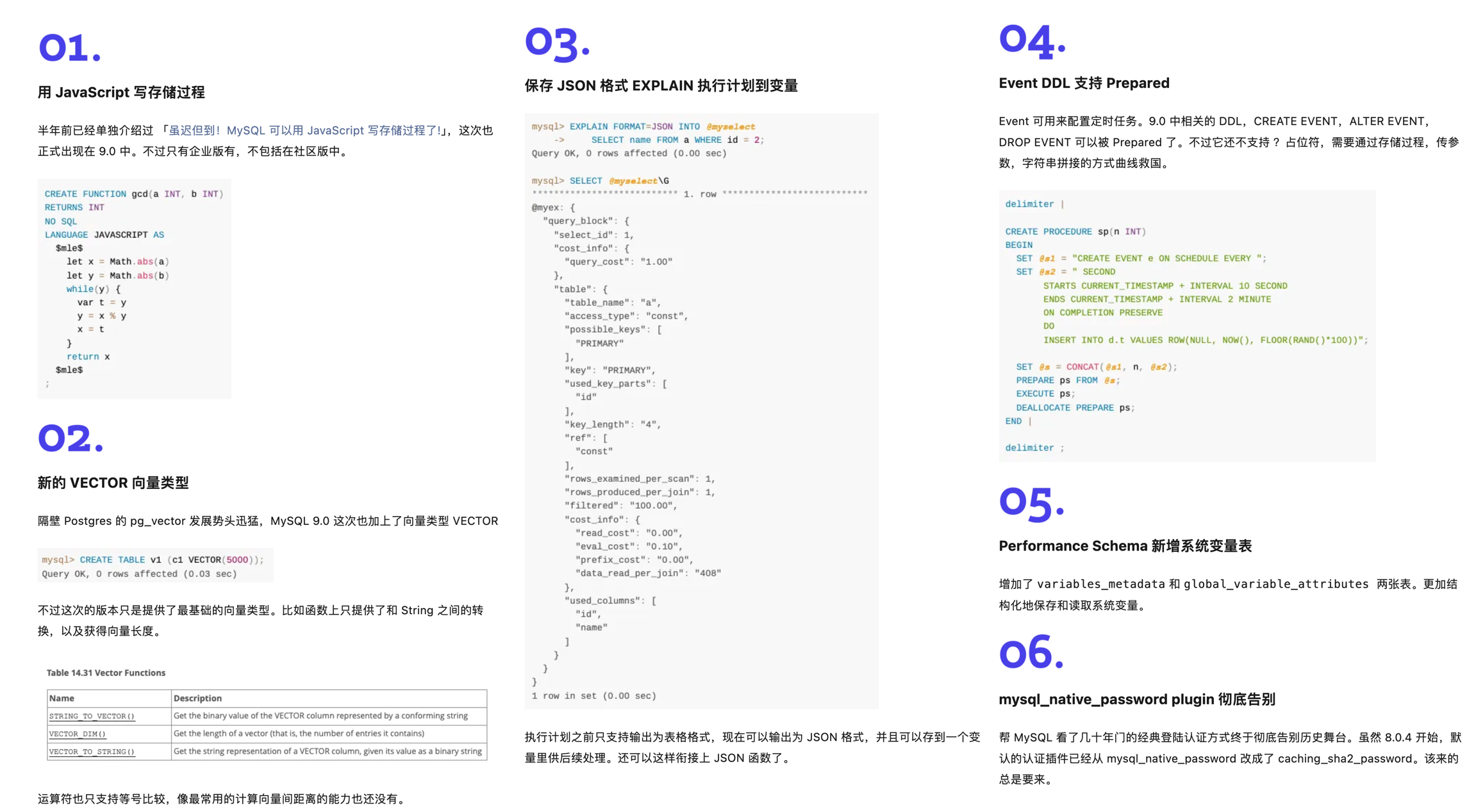

新版本

昨天,MySQL 发布了 “创新版本” 9.3 但是看上去和先前的 9.x 一样,都是些修修补补,看不到什么创新的东西。 搜索尚未发布的 PostgreSQL 18,你能看到无数特性预览的介绍文章;而搜索 MySQL 9.3,能看到的是社区对此的抱怨与失望。

MySQL 老司机丁奇看完 ReleaseNote 之后表示,《MySQL创新版正在逐渐失去它的意义》,德哥看后写了 《MySQL将保持平庸》。 对于 MySQL 的 “创新版本”,Percona CEO, Peter Zaitsev 也发三篇《MySQL将何去何从》,《Oracle最终还是杀死了MySQL》,《Oracle还能挽救MySQL吗》,公开表达了对 MySQL 的失望与沮丧。

在最近几年,MySQL 在新功能上乏善可陈,与突飞猛进的 PostgreSQL 形成了鲜明的对比。

新功能

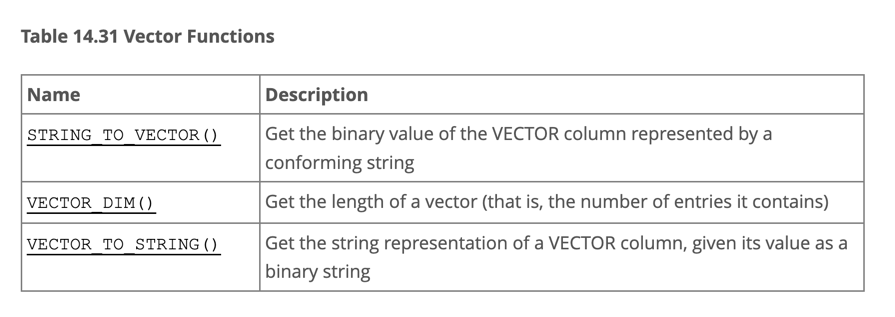

以数据库领域最近两年最为火爆的增量场景 —— 向量数据库为例。在前两年的 向量数据库热潮中,PostgreSQL 生态里就涌现出了至少六七款向量数据库扩展( pgvector,pgvector.rs,pg_embedding,latern,pase,pgvectorscale, vchord),并在你追我赶的赛马中卷出了新高度。最终在 AWS 的资源投入下,pgvector 在一年内实现了 150x 的性能飞跃,将整个专用向量数据库市场都给轰平了。

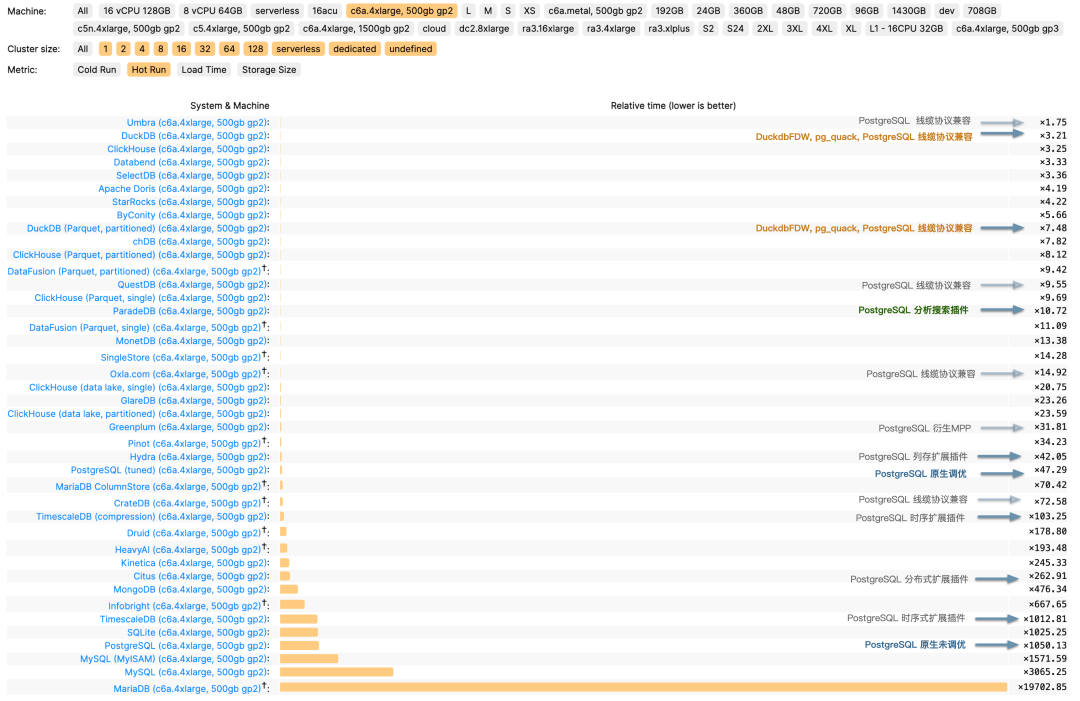

在当下,PostgreSQL 生态正在进行着 如火如荼的 DuckDB 缝合大赛 ,pg_duckdb 与 pg_mooncake 等扩展甚至已经进 ClickBench 分析性能榜单 T0 梯队,

也开始进入 Thoughtworks 技术雷达评估 Radar,正在攻克真正的 OLTP 与 OLAP 融合问题,旨在替代 OLAP 大数据全家桶。

与此同时进行的还有用于原地替代 ElasticSearch Tantivy/BM25 缝合大赛。

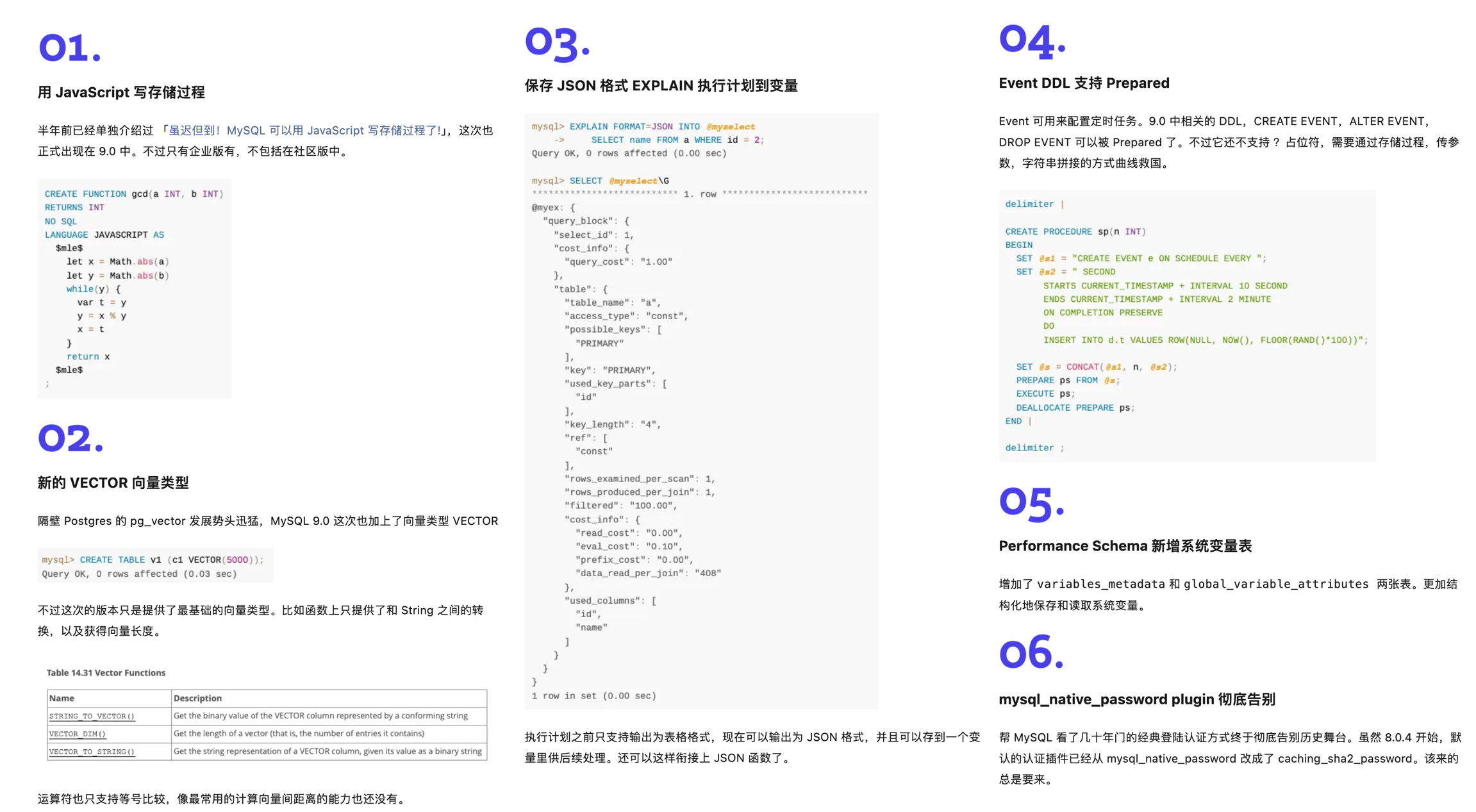

而 MySQL 在这段时间里更新了什么功能呢?一个不支持计算距离与索引的羞辱性 VECTOR 实现;还有一个企业版专属的 JS 存储过程支持(开源版没有!),而这是 PG 15 年前就可以通过 plv8 扩展实现的功能了。当 MySQL 还局限在 “关系型 OLTP 数据库” 的定位时, PostgreSQL 早已经放飞自我,从一个关系型数据库发展成了一个多模态的数据库,成为了一个数据管理的抽象框架与开发平台。

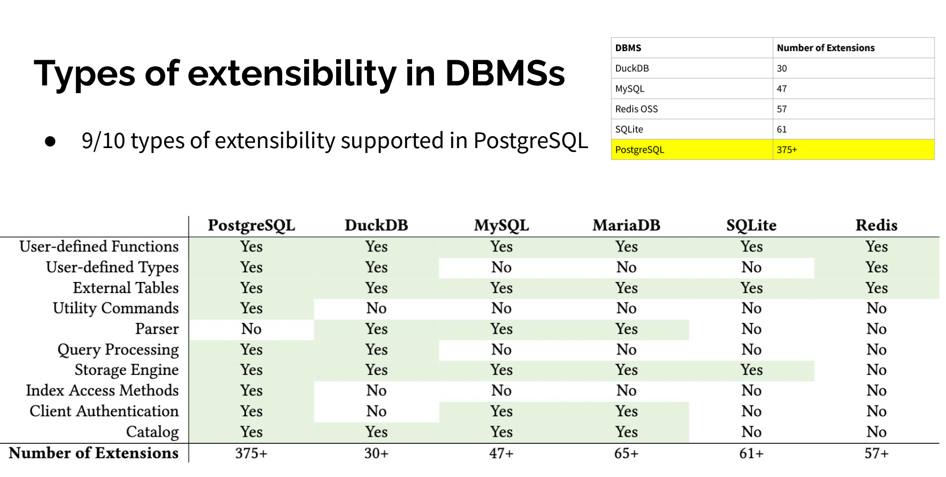

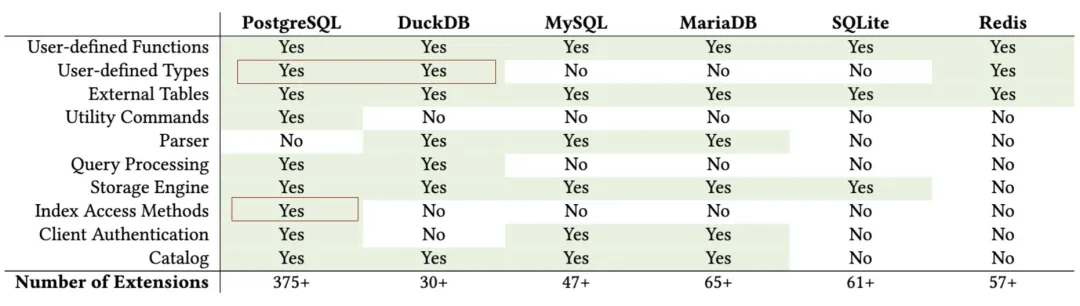

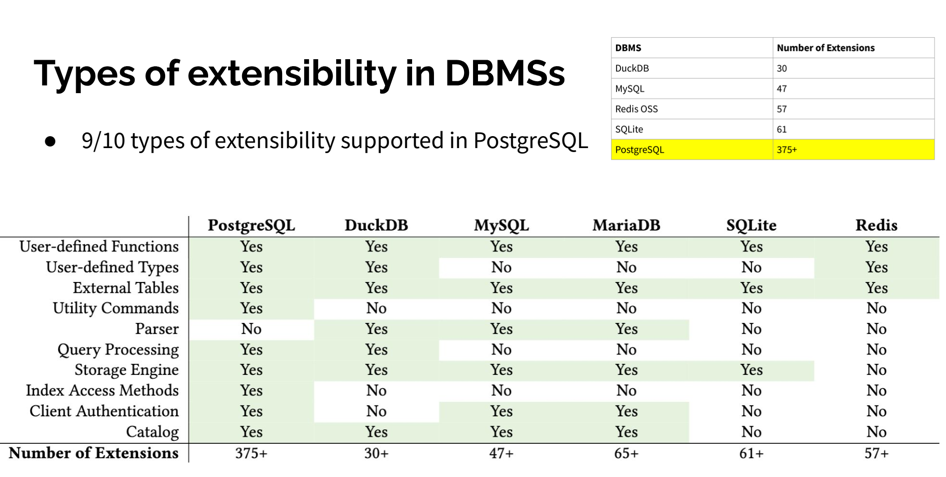

扩展性

来自 CMU 的 Abigale Kim 对主流数据库的可扩展性进行了研究:PostgreSQL 有着所有 DBMS 中最好的 可扩展性(Extensibility),以及其他数据库生态难望其项背的扩展插件数量 —— 375+,这还只是 PGXN 注册在案的实用插件,实际生态扩展总数已经破千。至少在开源的 PostgreSQL RDS 发行版 Pigsty 中,就已经开箱即用的提供 405 个扩展的 DEB/RPM 包了。

PostgreSQL 有着一个繁荣的扩展生态 —— 地理空间,时间序列,向量检索,机器学习,OLAP分析,全文检索,图数据库;这些扩展让 PostgreSQL 真正成为一专多长的全栈数据库 —— 单一数据库选型便可替代各式各样的专用组件: MySQL,MongoDB,Kafka,Redis,ElasticSearch,Neo4j,甚至是专用分析数仓与数据湖。

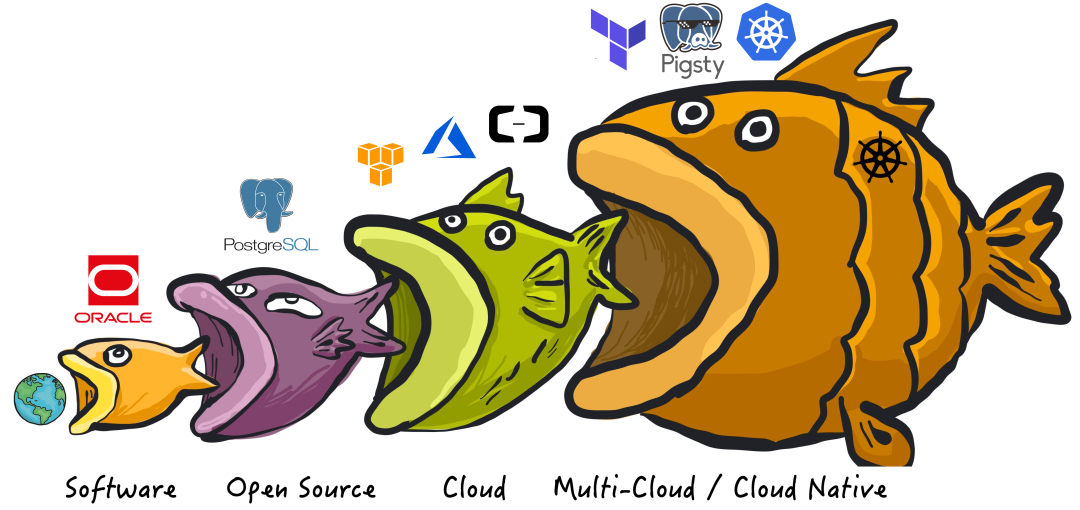

PostgreSQL正在吞噬数据库世界 —— 它正在通过插件的方式,将整个数据库世界内化其中。“一切皆用 Postgres” 也已经不再是少数精英团队的前沿探索,而是成为了一种进入主流视野的最佳实践。

而在新功能支持上,MySQL 却显得十分消极 —— 一个应该有大量 Breaking Change 的“创新大版本更新”,不是糊弄人的摆烂特性,就是企业级的特供鸡肋,一个大版本就连鸡零狗碎的小修小补都凑不够数。

兼容性

除了海量扩展外,PostgreSQL 生态还有更离谱的:兼容功能:你还可以使用扩展或者分支,实现对其他数据库的兼容。

| 内核 | 特色 | 交付形态 | 公司 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Citus | 分布式 HTAP / 多租户 | 扩展 | 微软 |

| DocumentDB | MongoDB 功能特性兼容 | 扩展 | 微软 |

| Babelfish | MSSQL 线缆协议兼容 | 内核分支 | AWS |

| FerretDB | MongoDB 线缆协议兼容 | 中间件 | Ferret |

| OrioleDB | 云原生Undo存储引擎 | 扩展+补丁内核 | Supabase |

| OpenHalo | MySQL 线缆协议 兼容 | 内核分支 | 易景 |

| IvorySQL | Oracle 语法特性兼容 | 内核分支 | 瀚高 |

| PolarDB | Aurora/RAC 特性兼容 | 内核分支 | 阿里云 |

| PolarDB O | Oracle 语法特性兼容 | 内核分支 | 阿里云 |

其中,openHalo 对 MySQL 生态可谓釜底抽薪 —— 在 PG 上直接兼容 MySQL 的线缆协议,这意味着 MySQL 应用可以在不改驱动/代码的情况下迁移到 PostgreSQL 上来。 另外,OrioleDB 在原生 PostgreSQL 的基础上,增加了云原生 Undo 存储引擎,支持高并发的分布式事务处理,号称实现了 4x 的吞吐量性能。

这并非纸面上的 PR 稿,这些内核/扩展都已经全部在 PostgreSQL 发行版 Pigsty 中作为开箱即用的 RDS 服务直接可用。

在这种性能怪兽面前,MySQL 将何去何从?

性能

缺少功能也许并不是一个无法克服的问题 —— 对于一个数据库来说,只要它能将自己的本职工作做得足够出彩,那么架构师总是可以多费些神,用各种其他的数据积木一起拼凑出所需的功能。

性能劣化的MYSQL

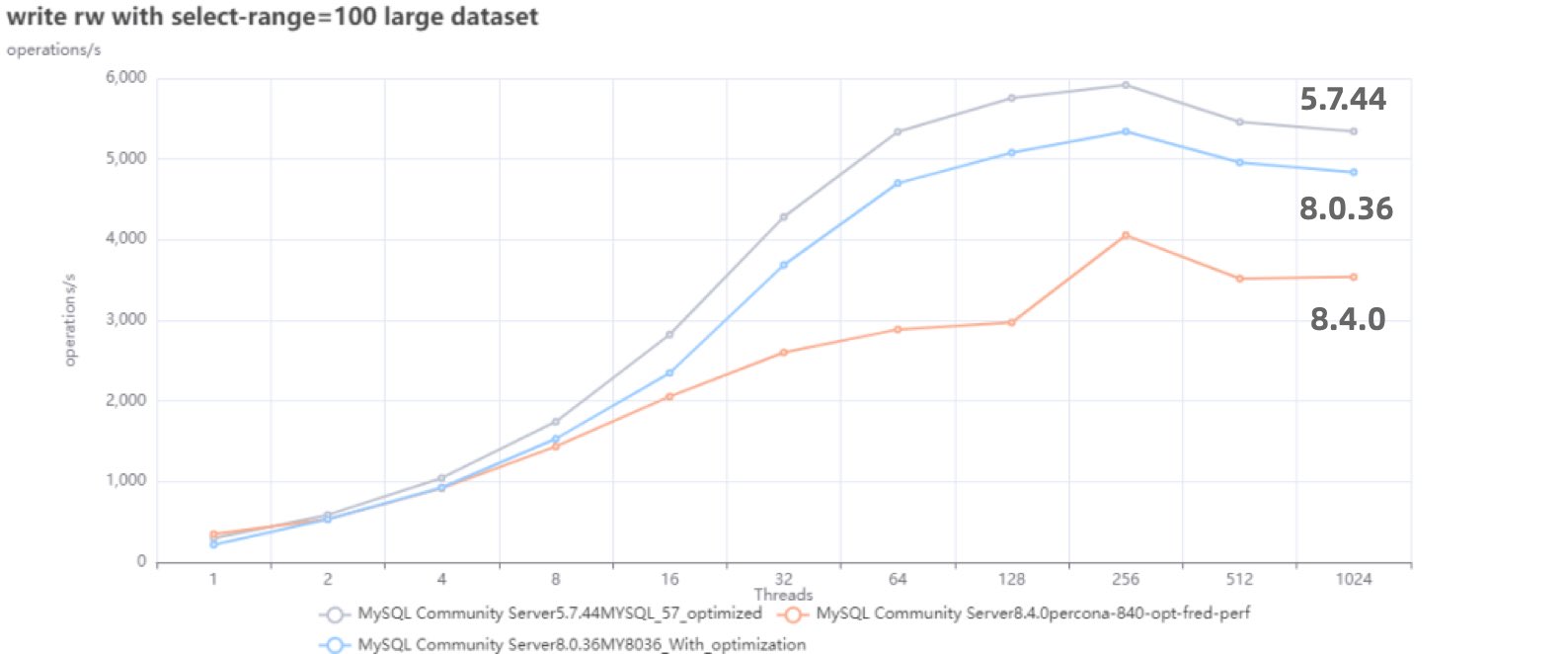

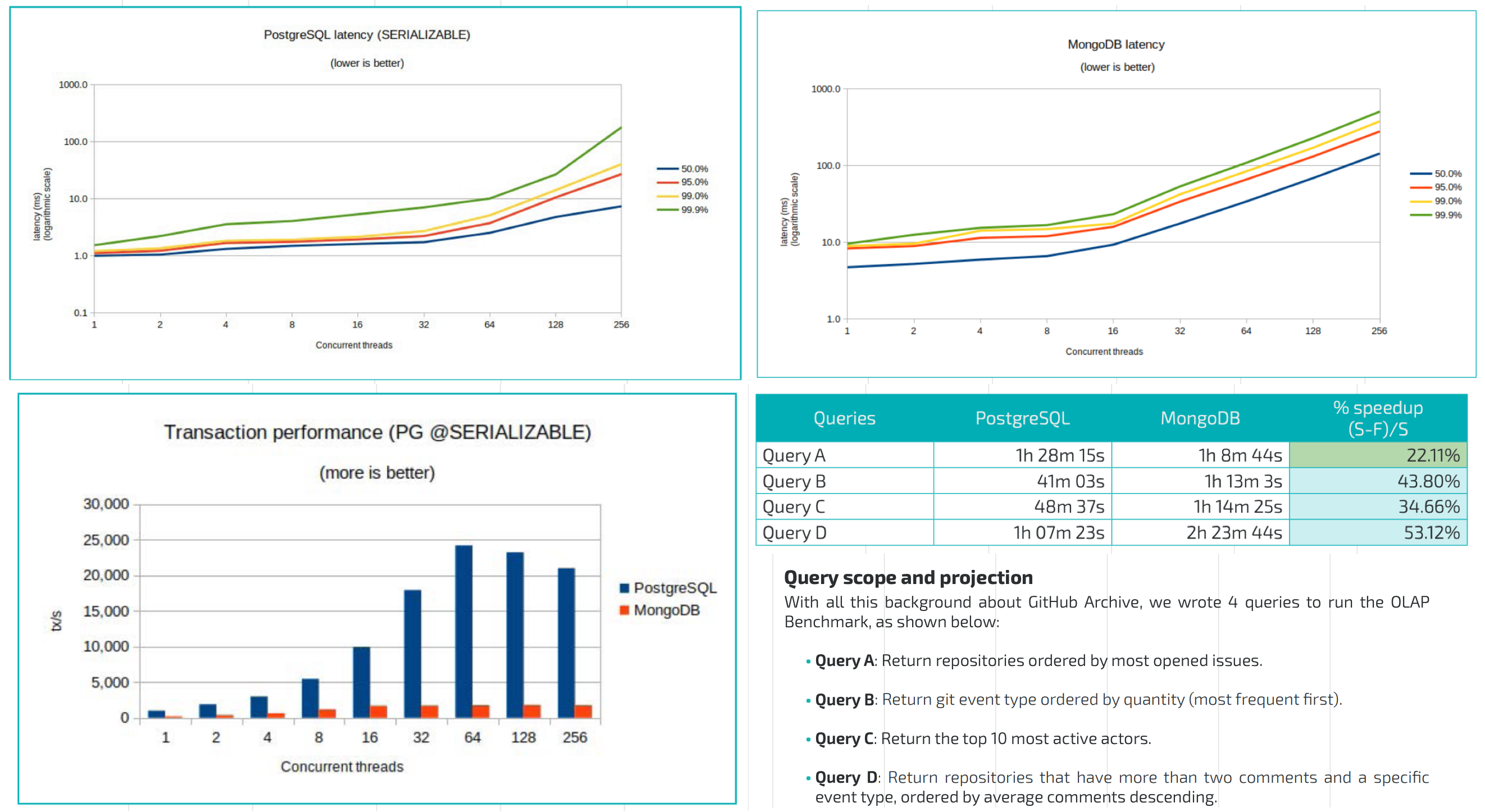

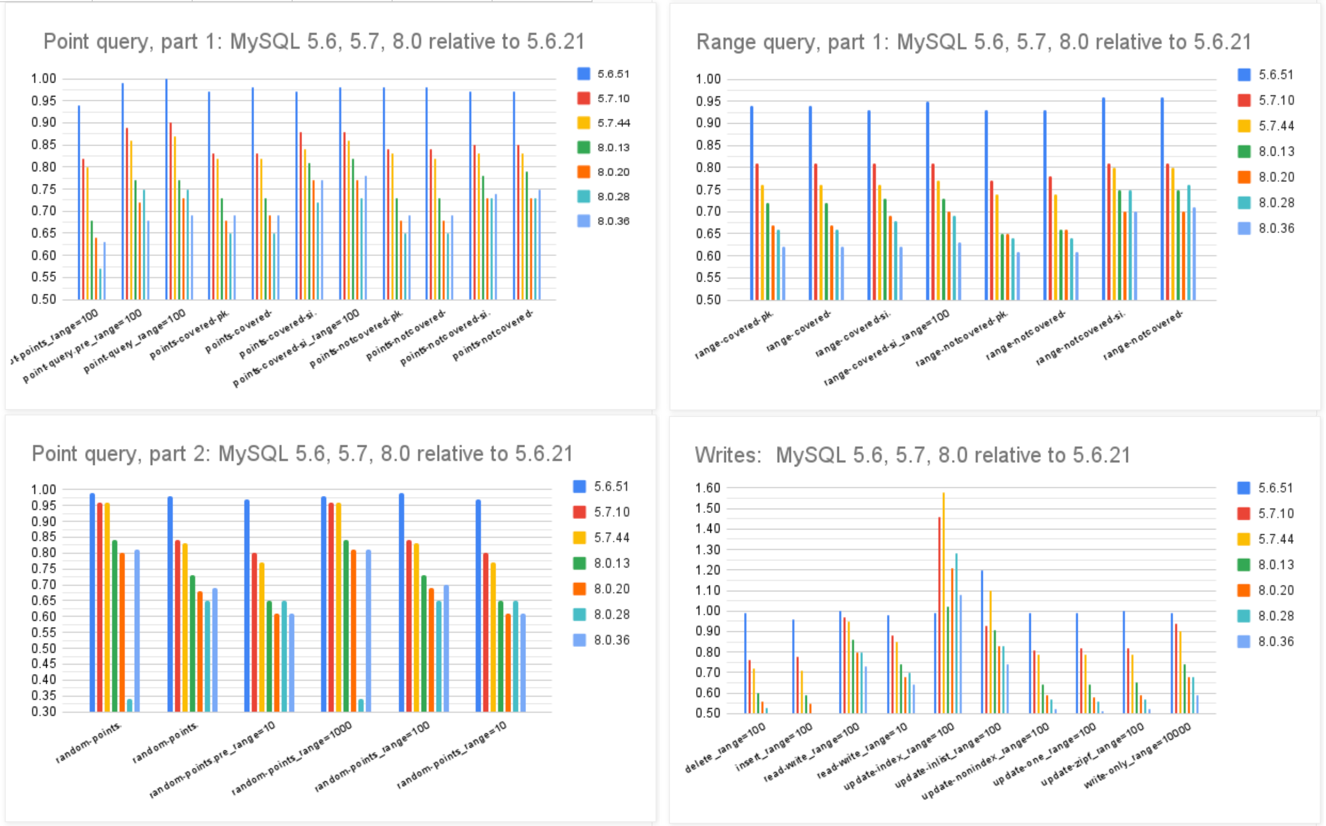

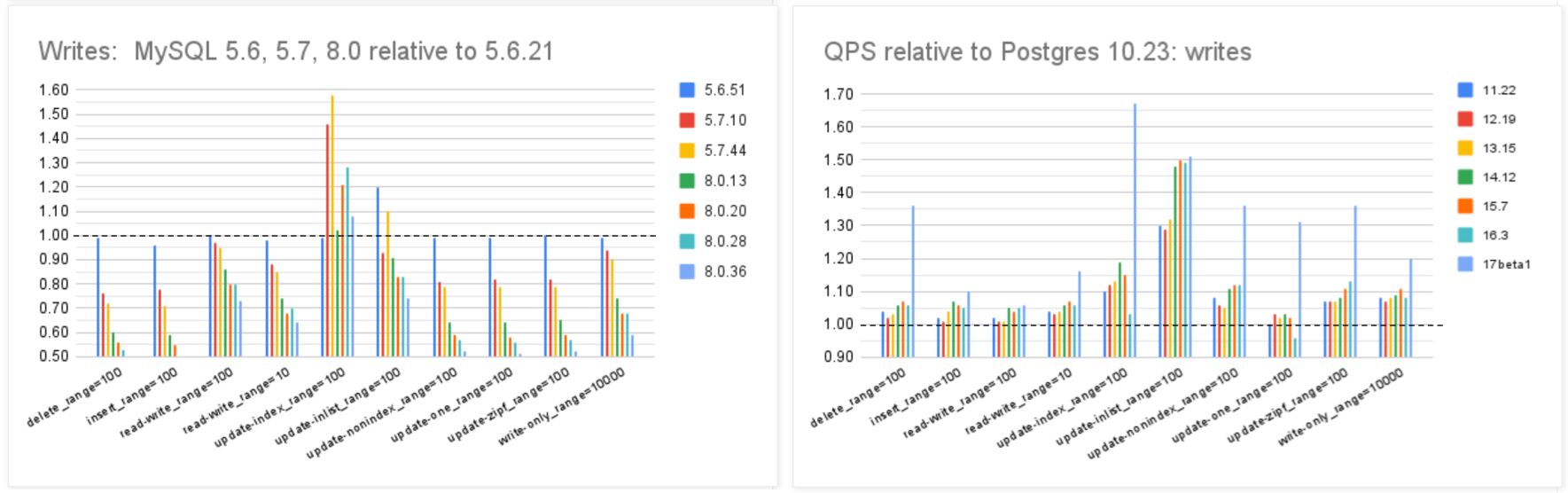

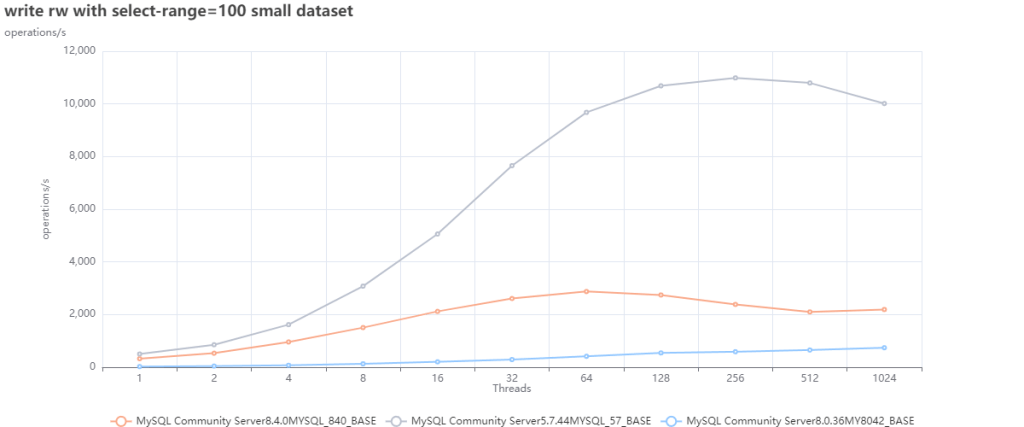

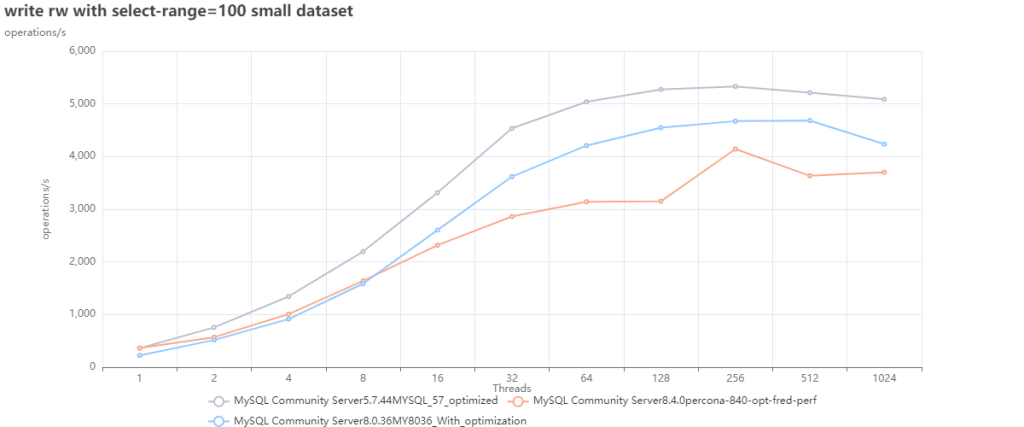

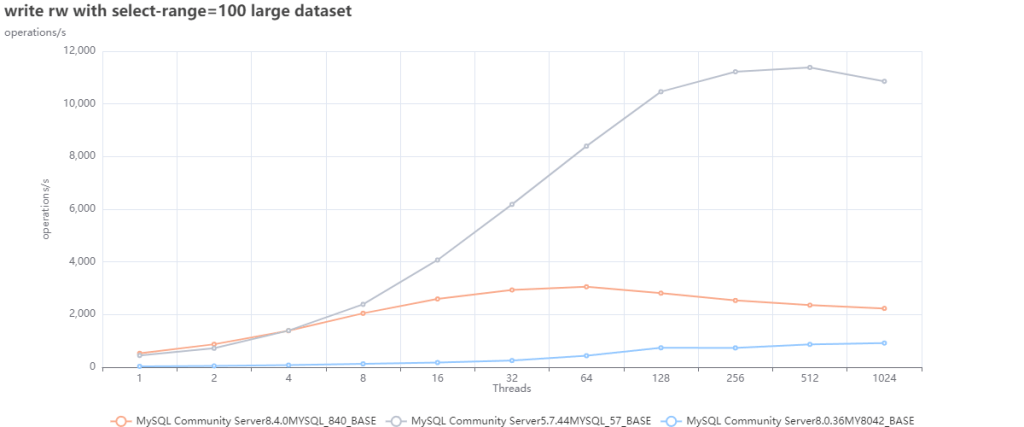

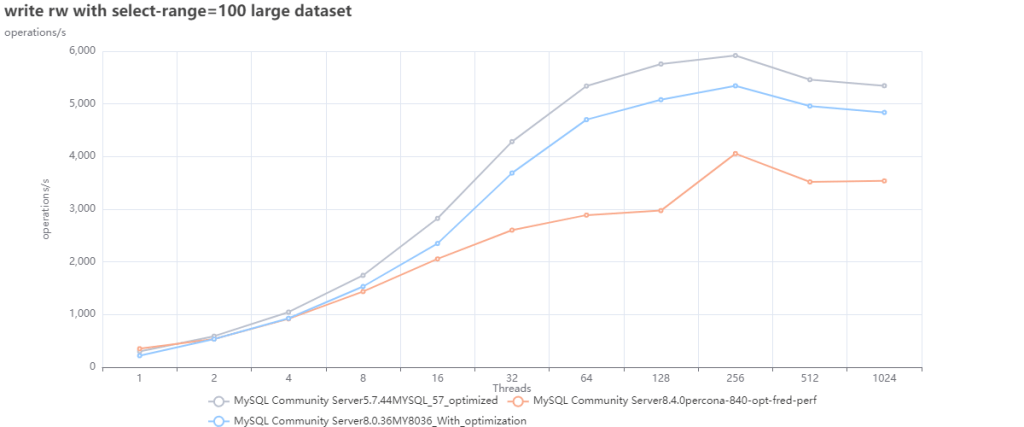

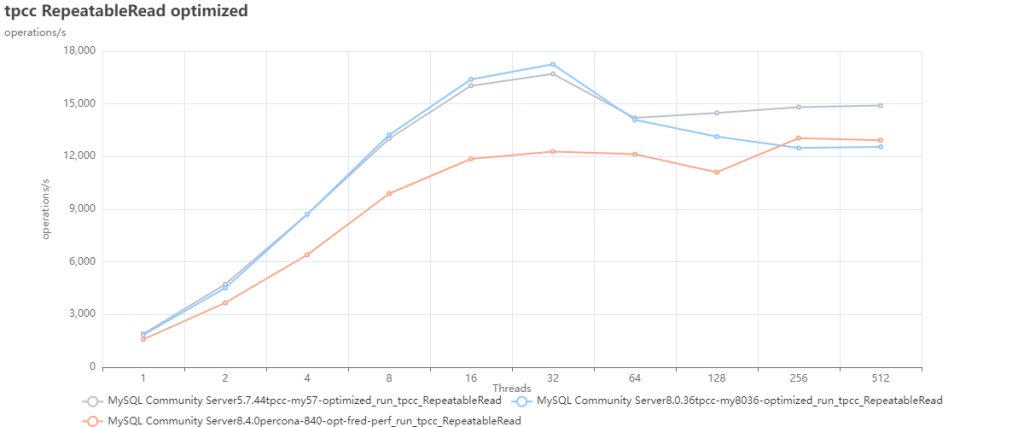

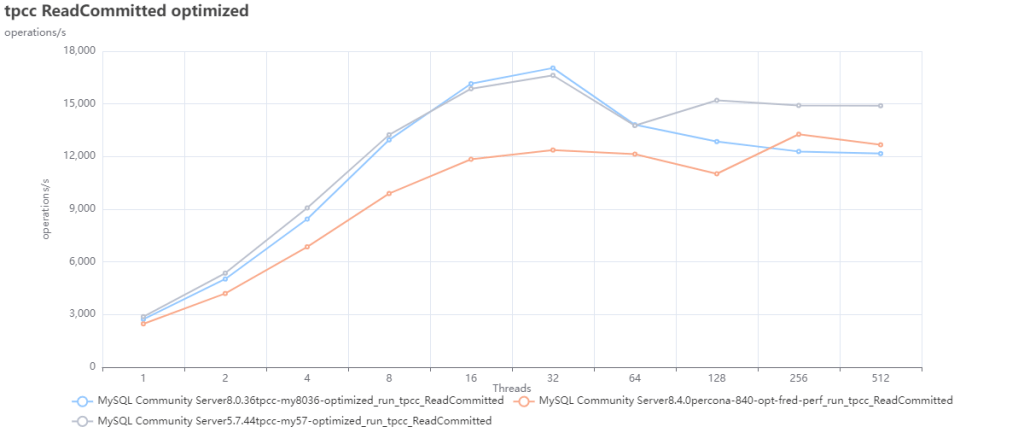

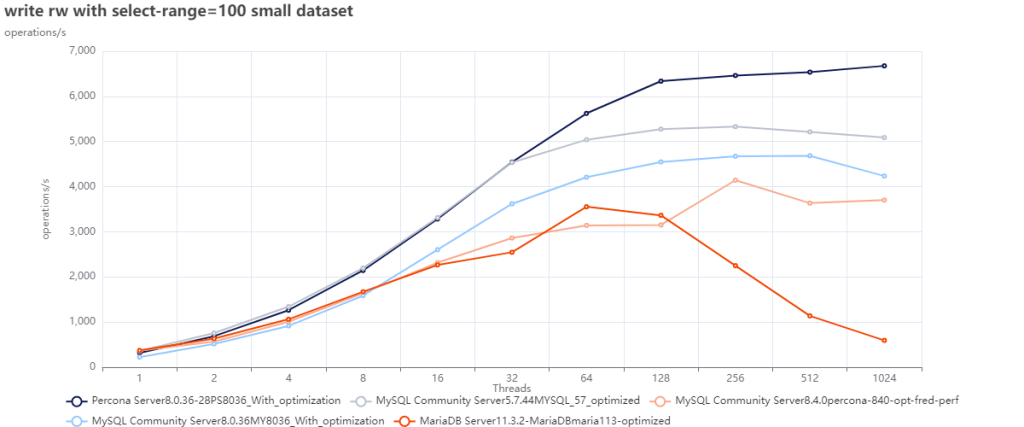

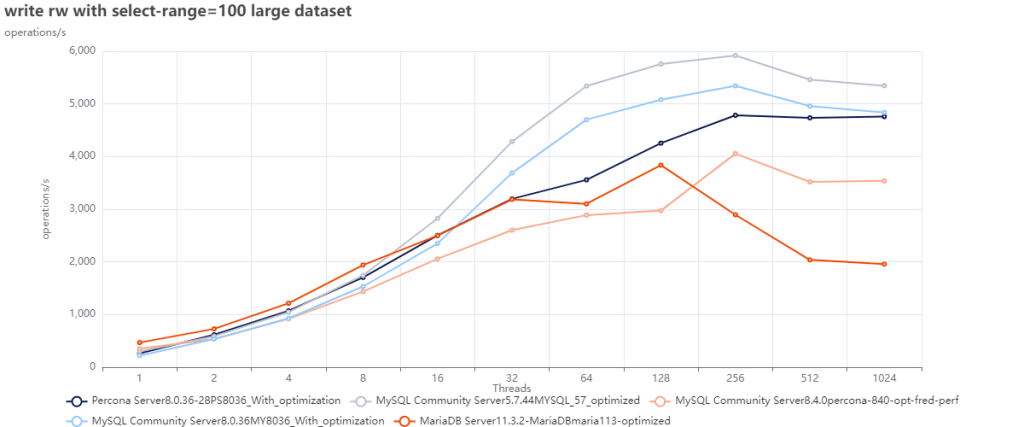

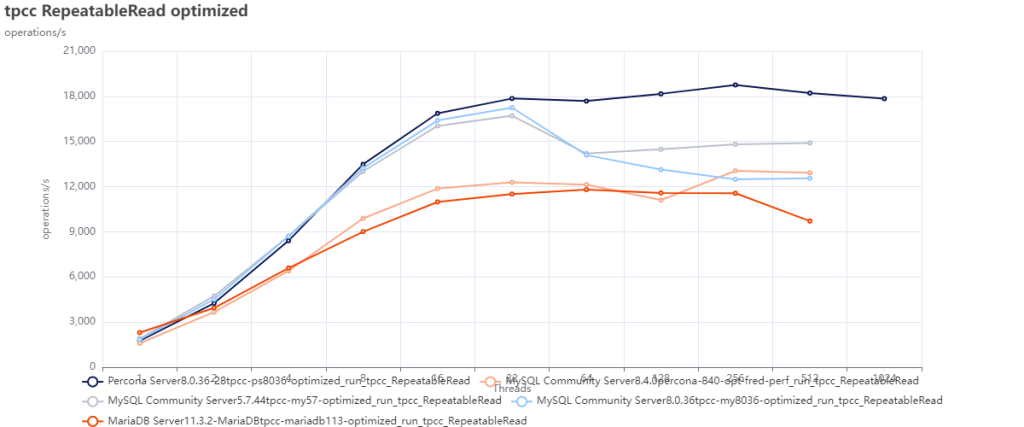

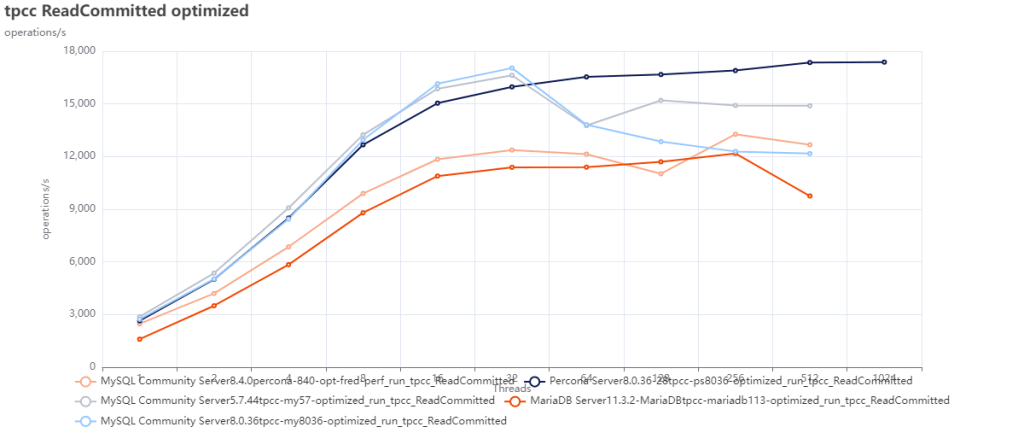

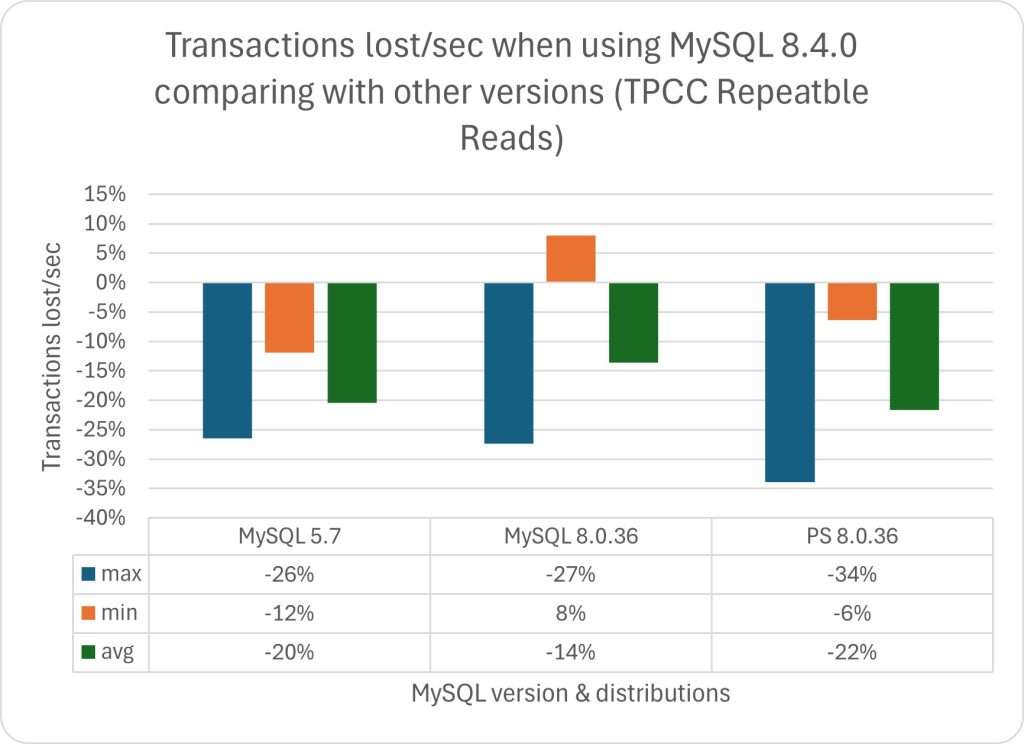

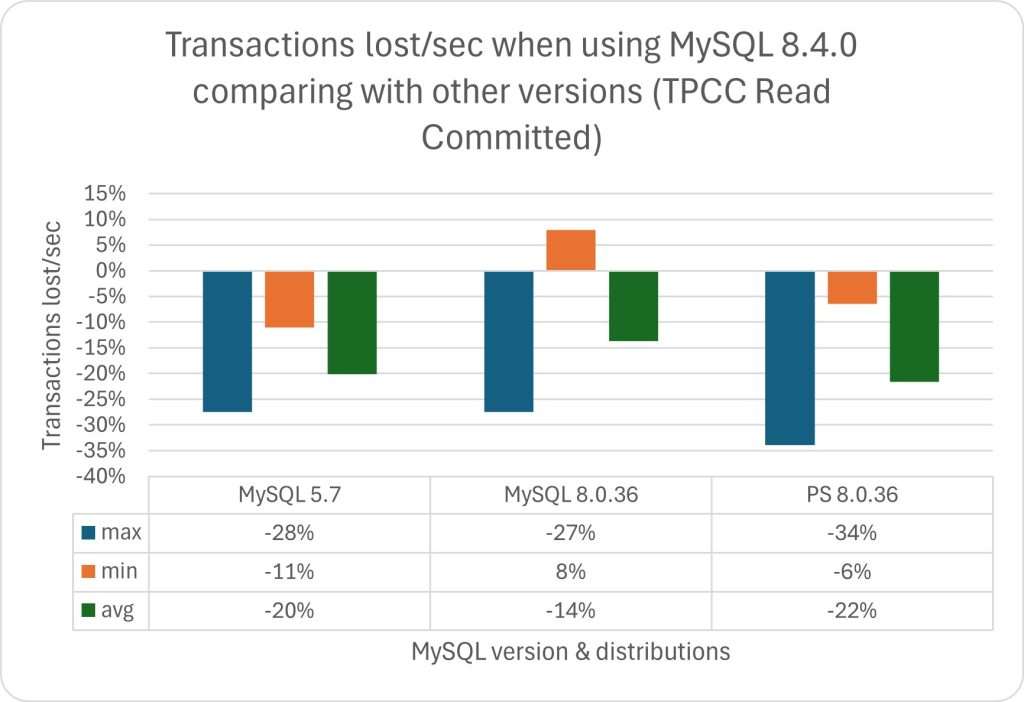

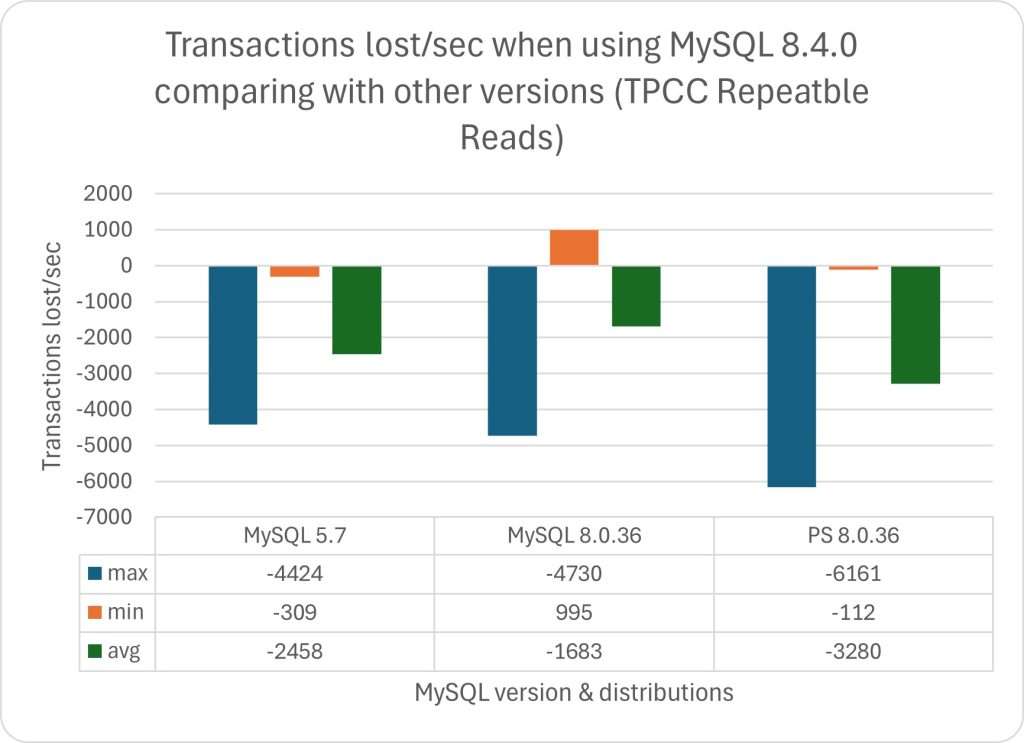

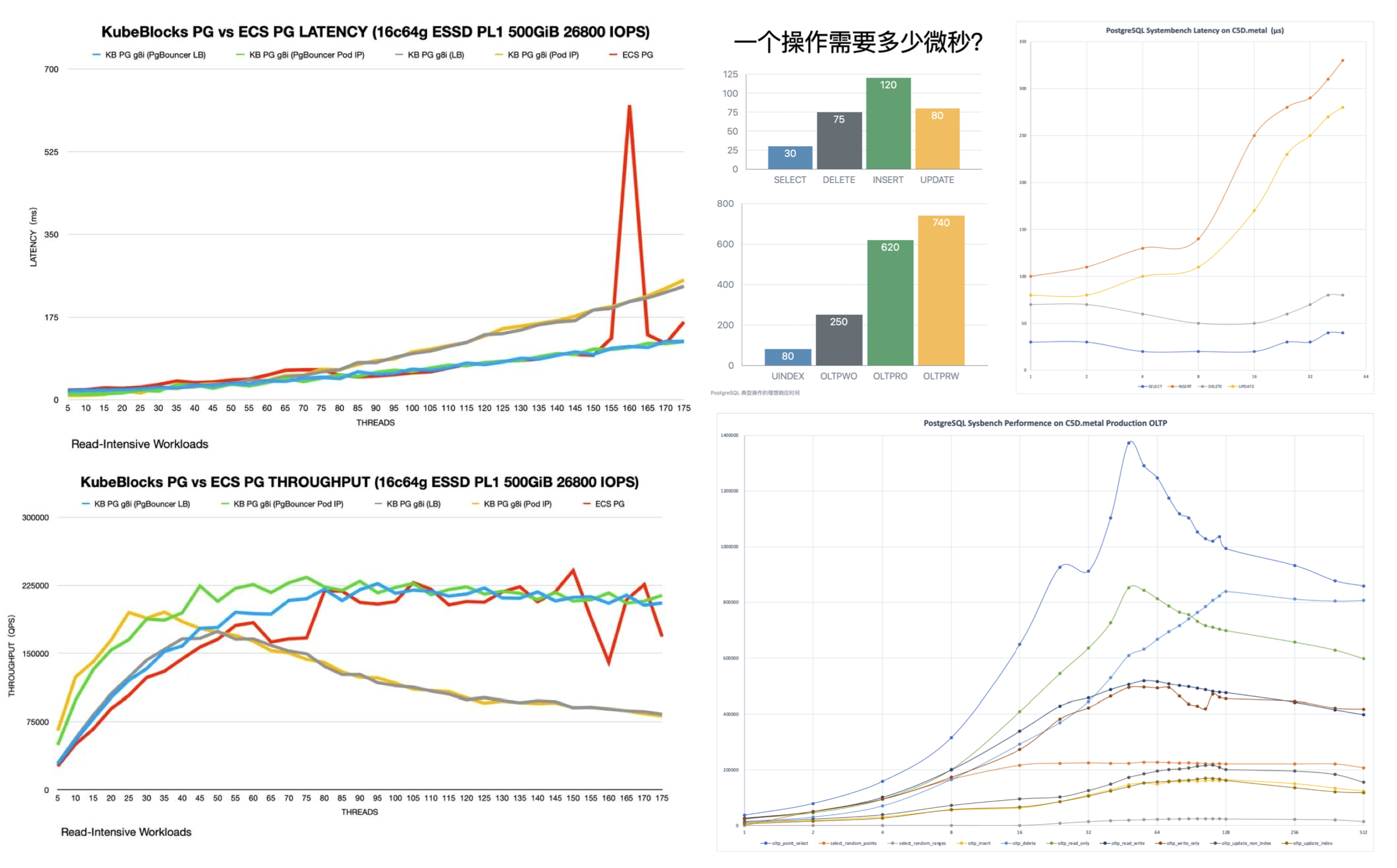

MySQL 曾引以为傲的核心特点便是 性能 —— 至少对于互联网场景下的简单 OLTP CURD 来说,它的性能是非常不错的。然而不幸地是,这一点也正在遭受挑战:Percona 的博文《Sakila:你将何去何从》中提出了一个令人震惊的结论:

MySQL 的版本越新,性能反而越差。

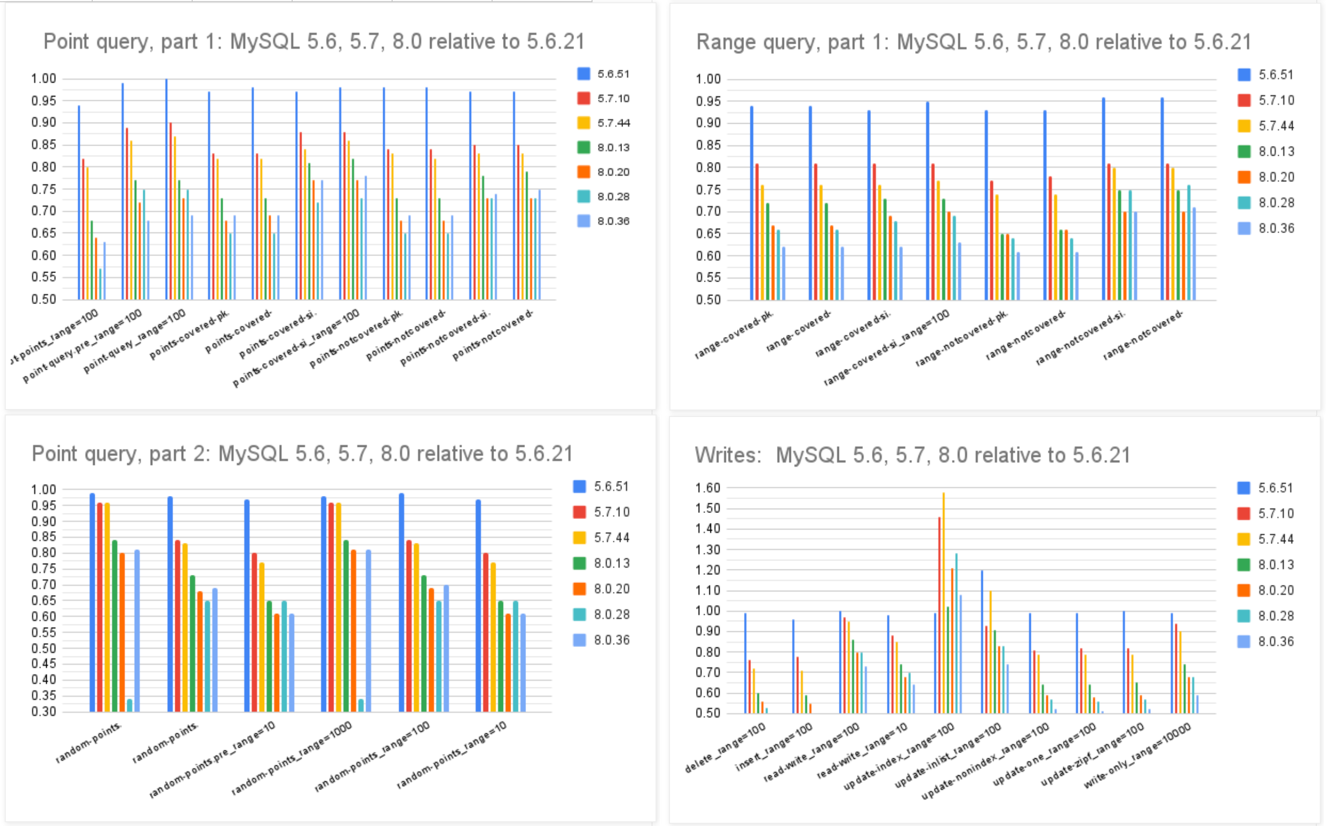

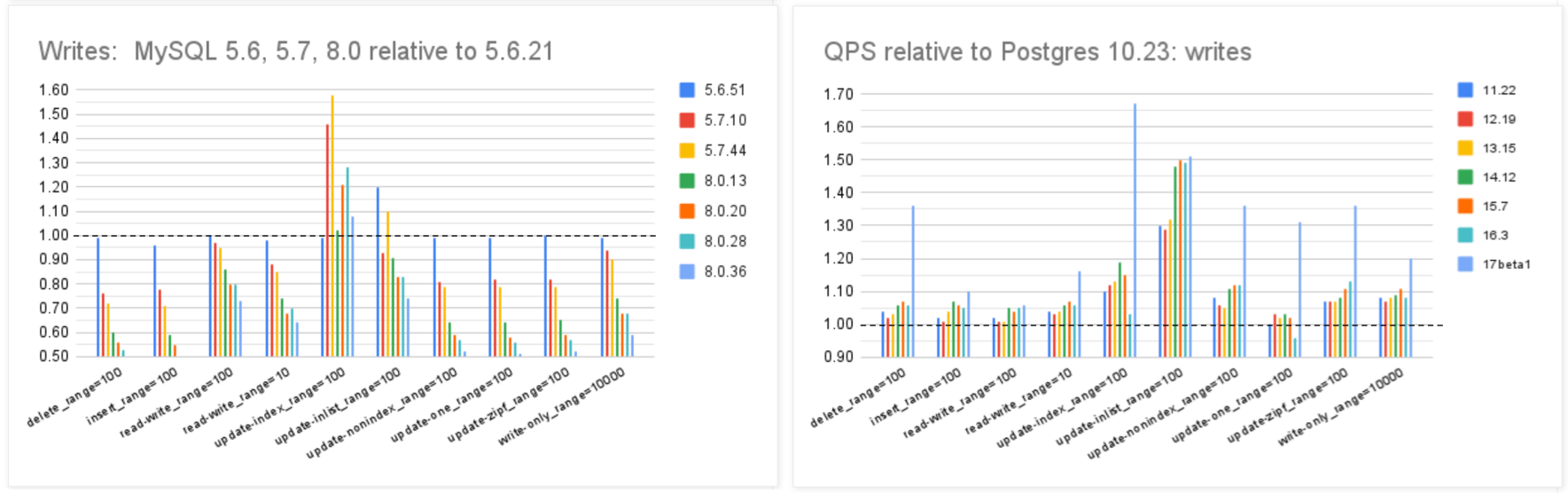

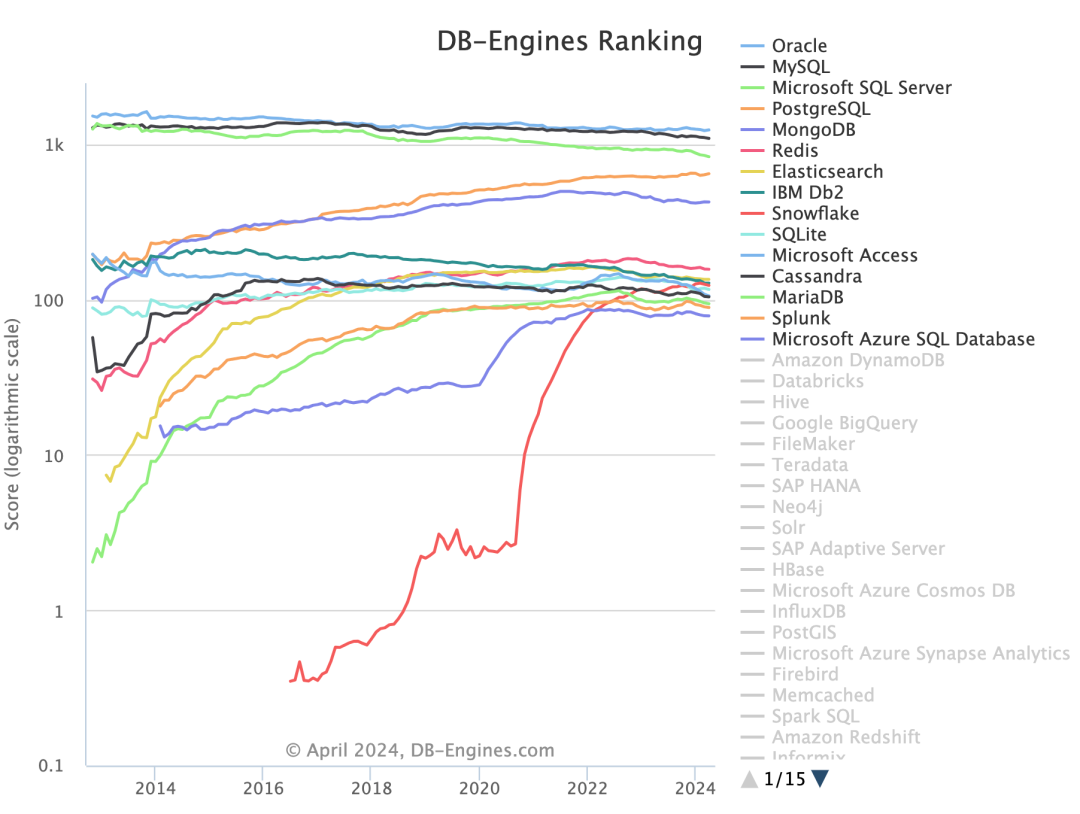

根据 Percona 的测试,在 sysbench 与 TPC-C 测试下,最新 MySQL 8.4 版本的性能相比 MySQL 5.7 出现了平均高达 20% 的下降。而 MySQL 专家 Mark Callaghan 进一步进行了 详细的性能回归测试,确认了这一现象:

MySQL 8.0.36 相比 5.6 ,QPS 吞吐量性能下降了 25% ~ 40% !

鸡肋的分析性能

尽管 MySQL 的优化器在 8.x 有一些改进,一些复杂查询场景下的性能有所改善,但分析与复杂查询本来就不是 MySQL 的长处与适用场景,只能说聊胜于无。相反,如果作为基本盘的 OLTP CRUD 性能出了这么大的折损,那确实是完全说不过去的。

ClickBench:MySQL 打这个榜确实有些不明智

Peter Zaitsev 在博文《Oracle最终还是杀死了MySQL》中评论:“与 MySQL 5.6 相比,MySQL 8.x 单线程简单工作负载上的性能出现了大幅下滑。你可能会说增加功能难免会以牺牲性能为代价,但 MariaDB 的性能退化要轻微得多,而 PostgreSQL 甚至能在 新增功能的同时显著提升性能”。

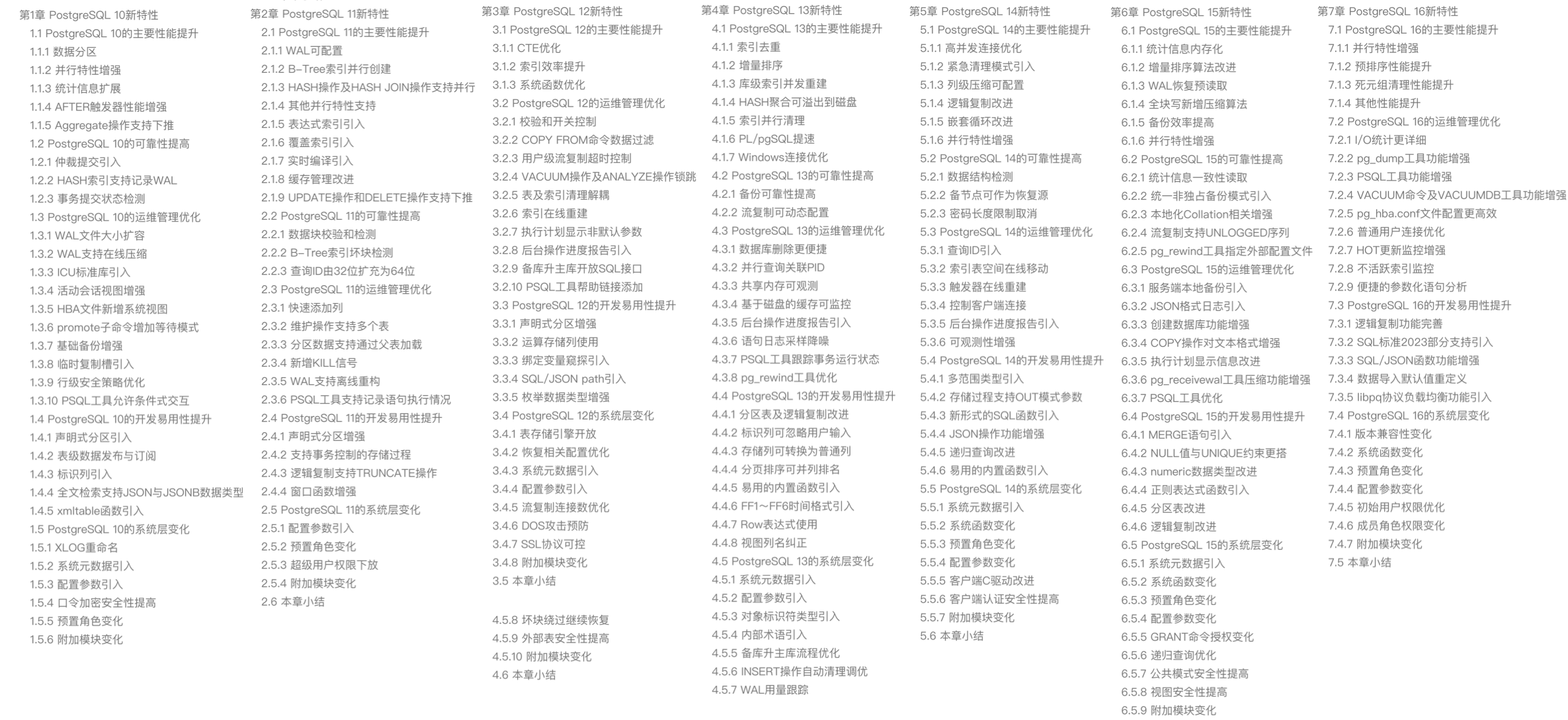

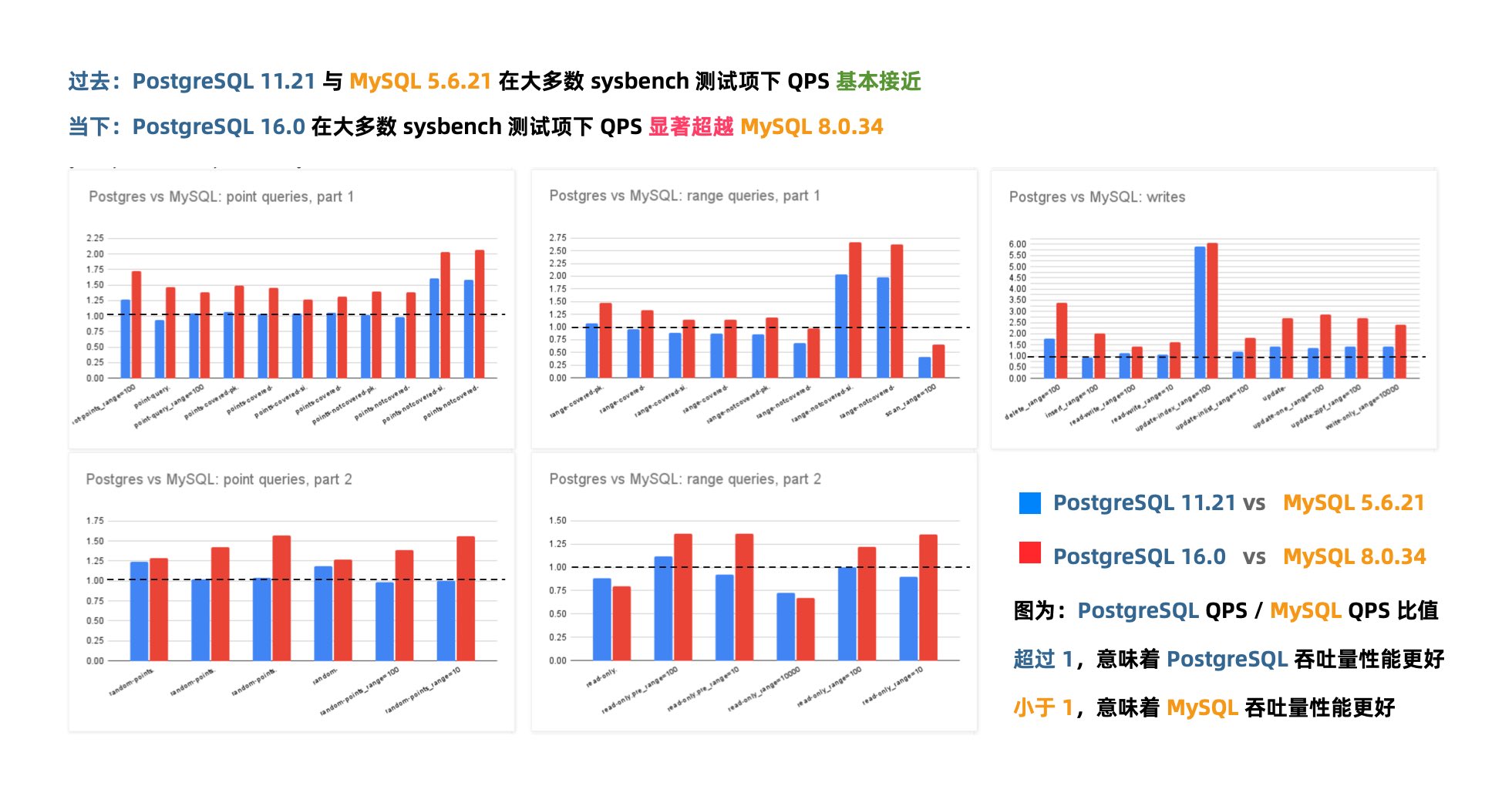

稳步提升的PostgreSQL性能

MySQL的性能随版本更新而逐步衰减,但在同样的性能回归测试中,PostgreSQL 性能却可以随版本更新有着稳步提升。特别是在最关键的写入吞吐性能上,最新的 PostgreSQL 17beta1 相比六年前的 PG 10 甚至有了 30% ~ 70% 的提升。

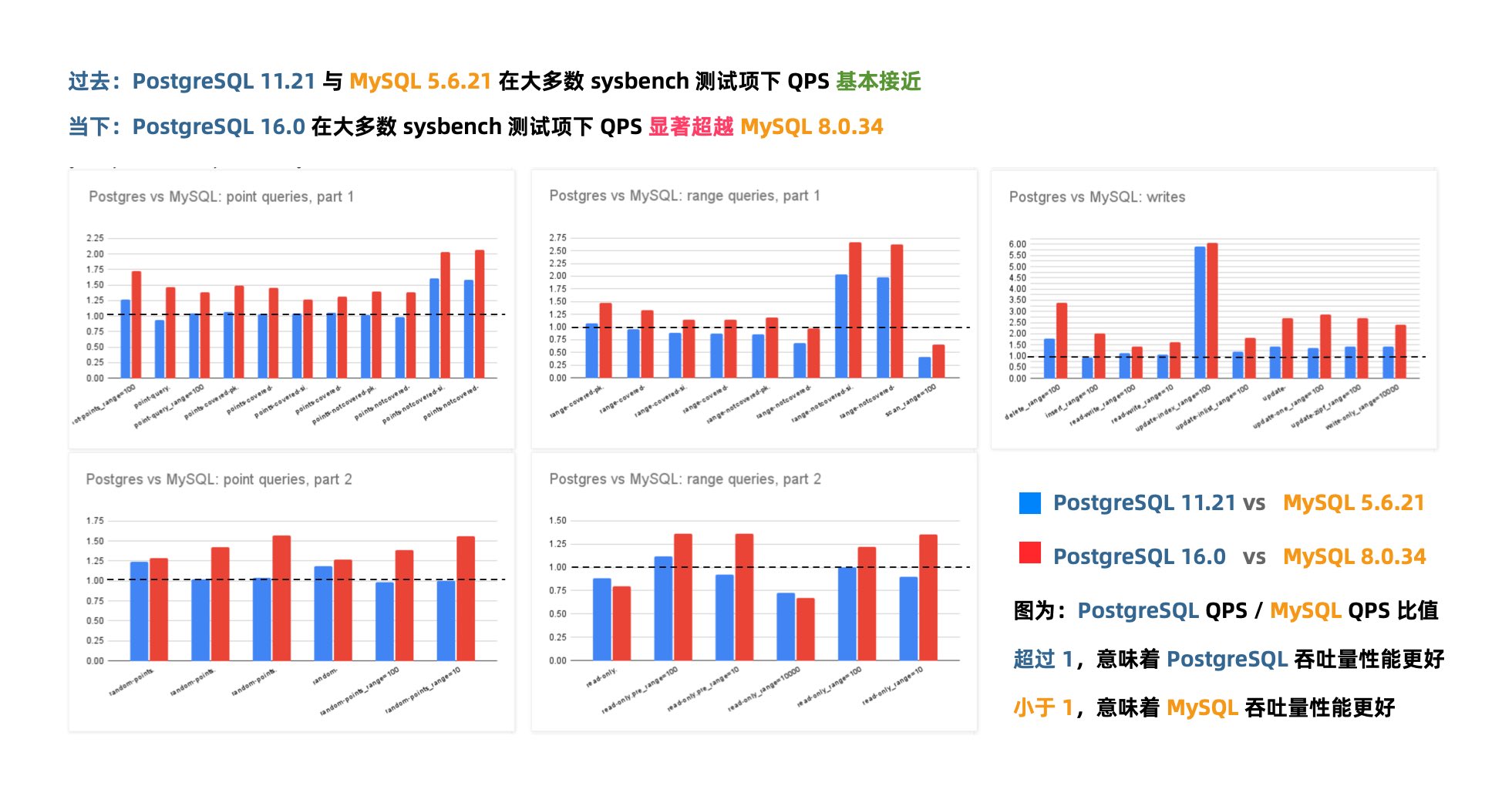

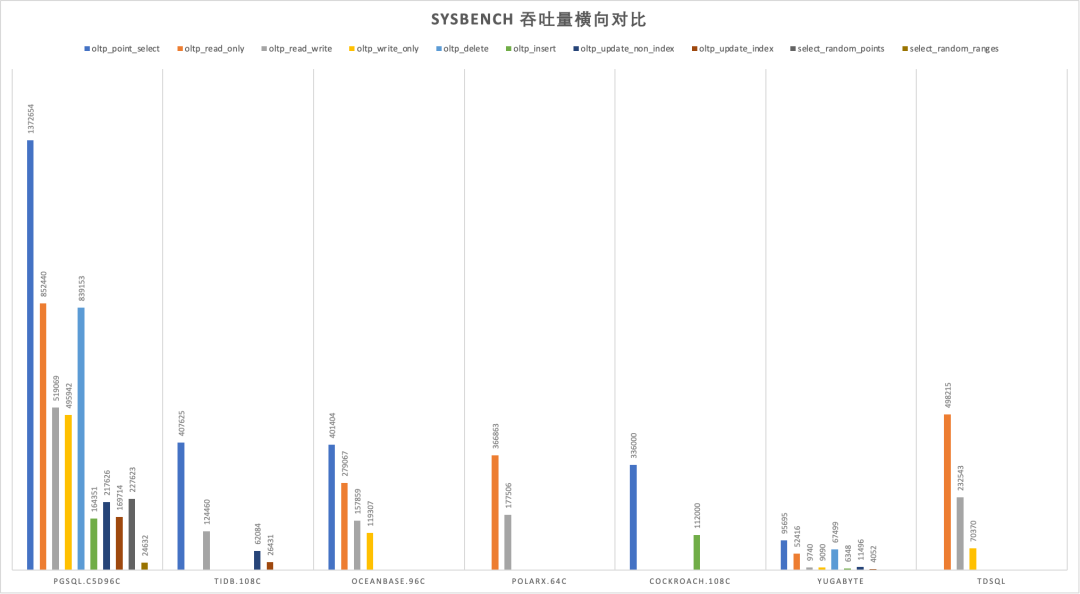

在 Mark Callaghan 的 性能横向对比 (sysbench 吞吐场景) 中,我们可以看到五年前 PG 11 与 MySQL 5.6 的性能比值(蓝),与当下 PG 16 与 MySQL 8.0.34 的性能比值(红)。PostgreSQL 和 MySQL 的性能差距在这五年间拉的越来越大。

几年前的业界共识是 PostgreSQL 与 MySQL 在 简单 OLTP CRUD 场景 下的性能基本相同。然而此消彼长之下,现在 PostgreSQL 的性能已经远远甩开 MySQL 了。 PostgreSQL 的各种读吞吐量相比 MySQL 高 25% ~ 100% 不等,在一些写场景下的吞吐量更是达到了 200% 甚至 500% 的恐怖水平。

在真实场景中的对比

一个有趣的佐证是知名开源项目 JuiceFS 对不同数据库作为元数据引擎的性能测试。

在这个例子中,我们可以很清晰的看出 MySQL 和 PostgreSQL 在一个真实三方评测中的性能差距。

MySQL 赖以安身立命的性能优势,已经不复存在了。

关于 PostgreSQL 与 MySQL 与 PostgreSQL 的性能评测,我建议各位参考 Mark Callaghan 发表在 Small Datum 上的文章。这是前 Google / Meta 的 MySQL Tech Lead 。 尽管他的主要职业生涯在与 MySQL,Oracle,MongoDB 打交道,并非 PostgreSQL 专家,但他严谨的测试方法与结果分析为读者带来了许多数据库性能方面的洞见。

- Postgres 17.4 与大型服务器上的 sysbench

- https://smalldatum.blogspot.com/2025/03/at-what-level-of-concurrency-do-mysql.html

质量

如果新版本只是性能不好,总归还有办法来优化修补。但如果是质量出了问题,那真就是无可救药了。

正确性

例如,Percona 最近刚刚在 MySQL 8.0.38 以上的版本(8.4.x, 9.0.0)中发现了一个 严重Bug —— 如果数据库里表超过 1万张,那么重启的时候 MYSQL 服务器会直接崩溃! 一个数据库里有1万张表并不常见,但也并不罕见 —— 特别是当用户使用了一些分表方案,或者应用会动态创建表的时候。而直接崩溃显然是可用性故障中最严重的一类情形。

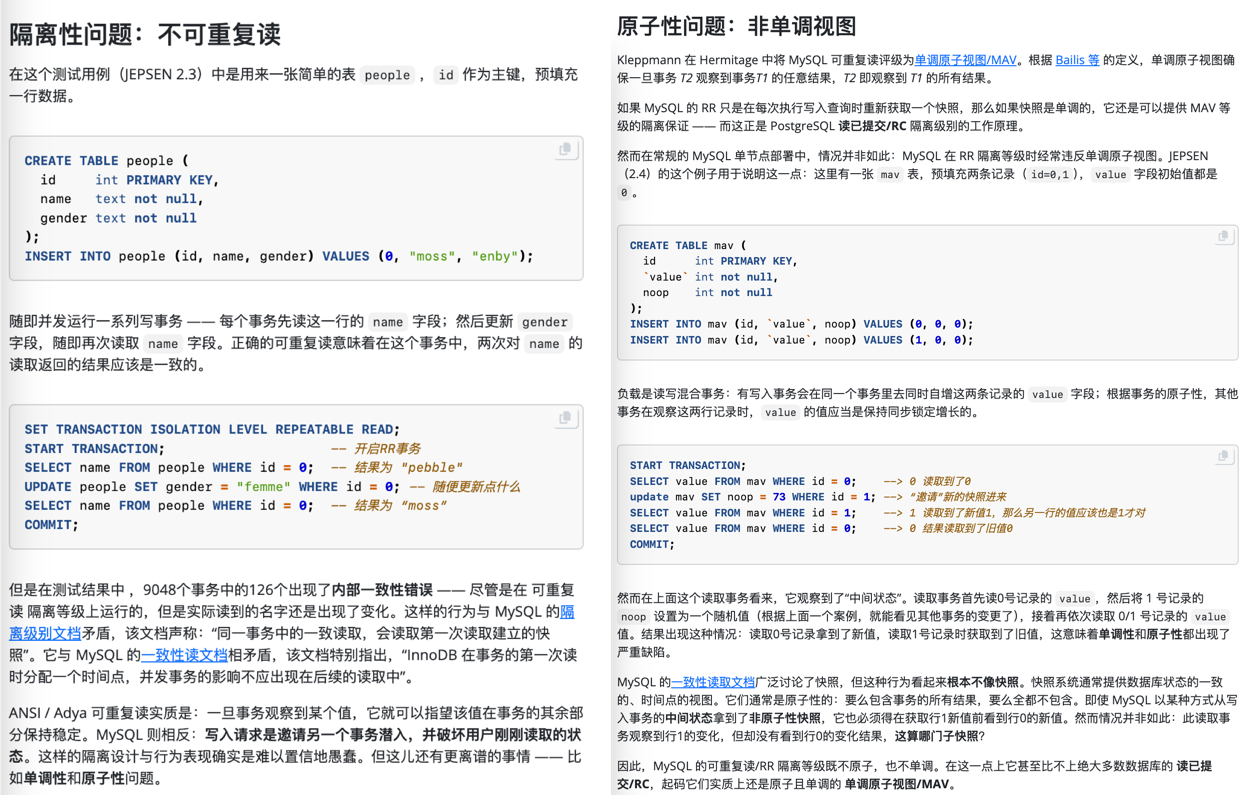

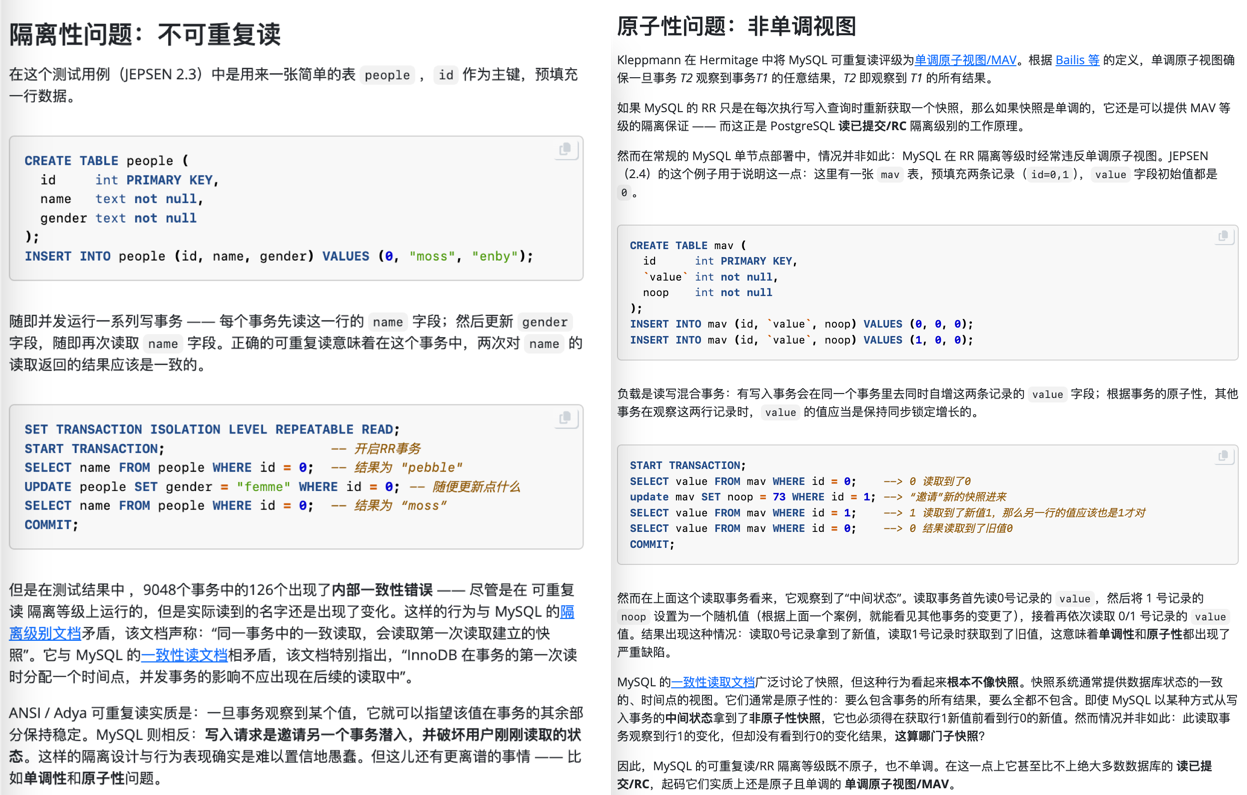

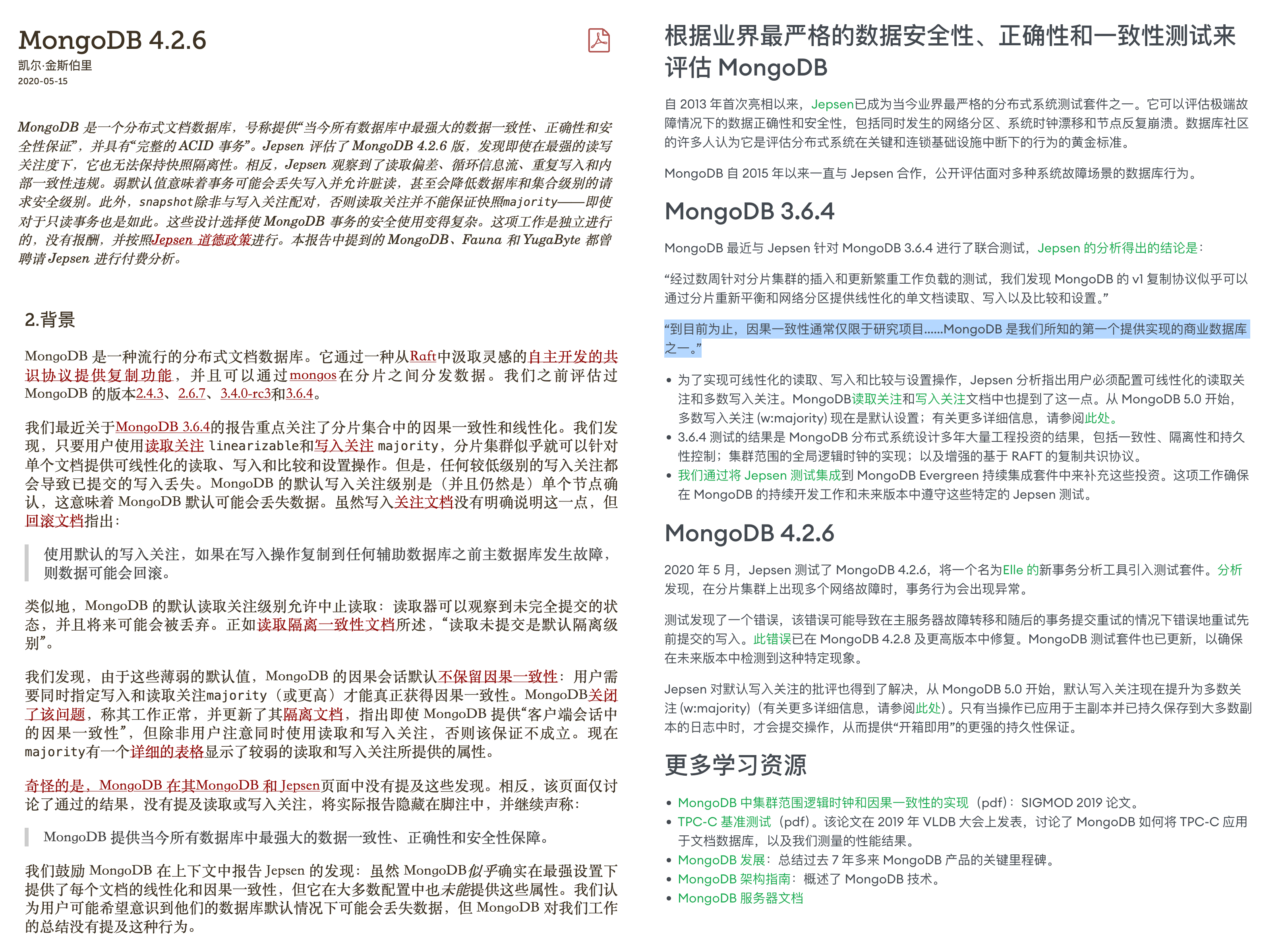

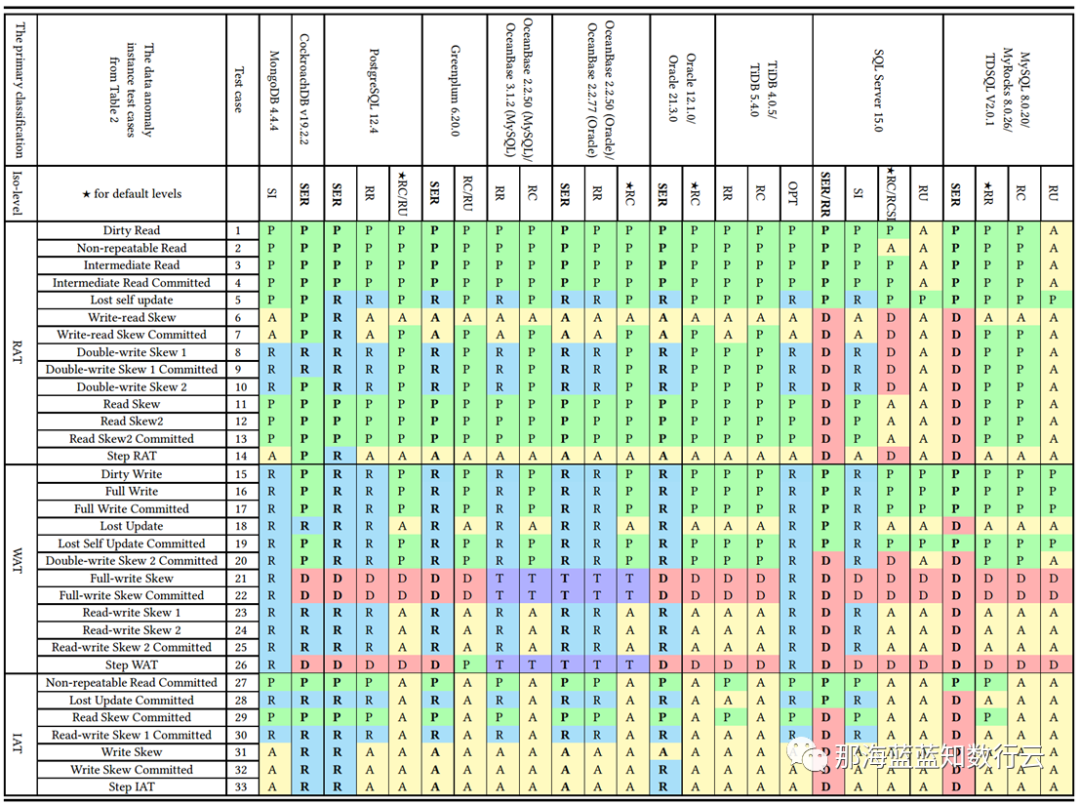

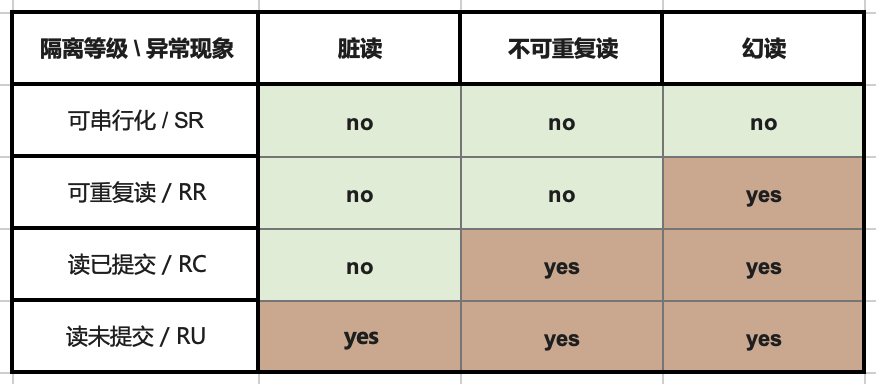

但 MySQL 的问题不仅仅是几个软件 Bug,而是根本性的问题 —— 《MySQL 糟糕的 ACID 正确性》指出,在正确性这个体面数据库产品必须的基本属性上,MySQL 的表现一塌糊涂。

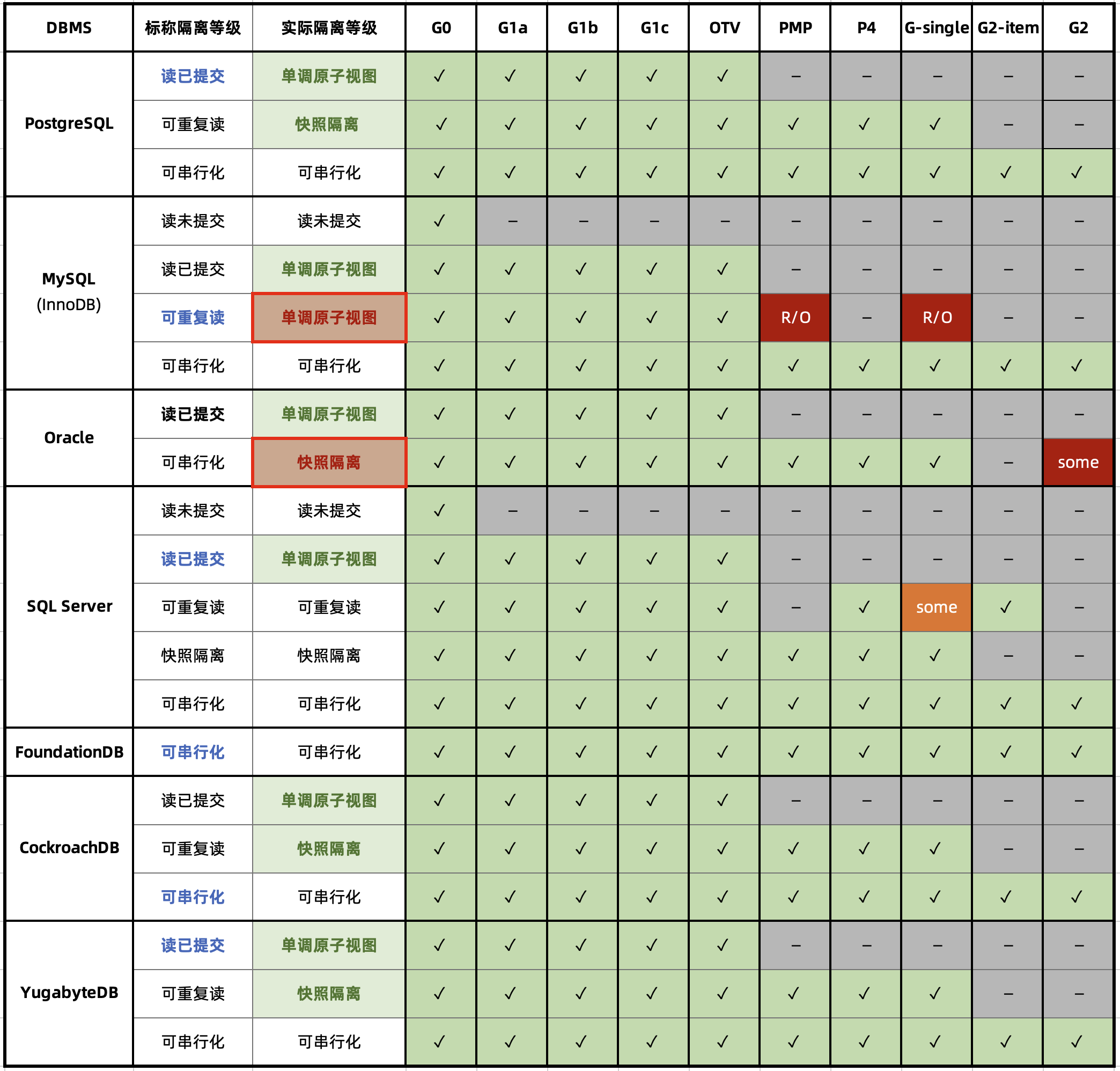

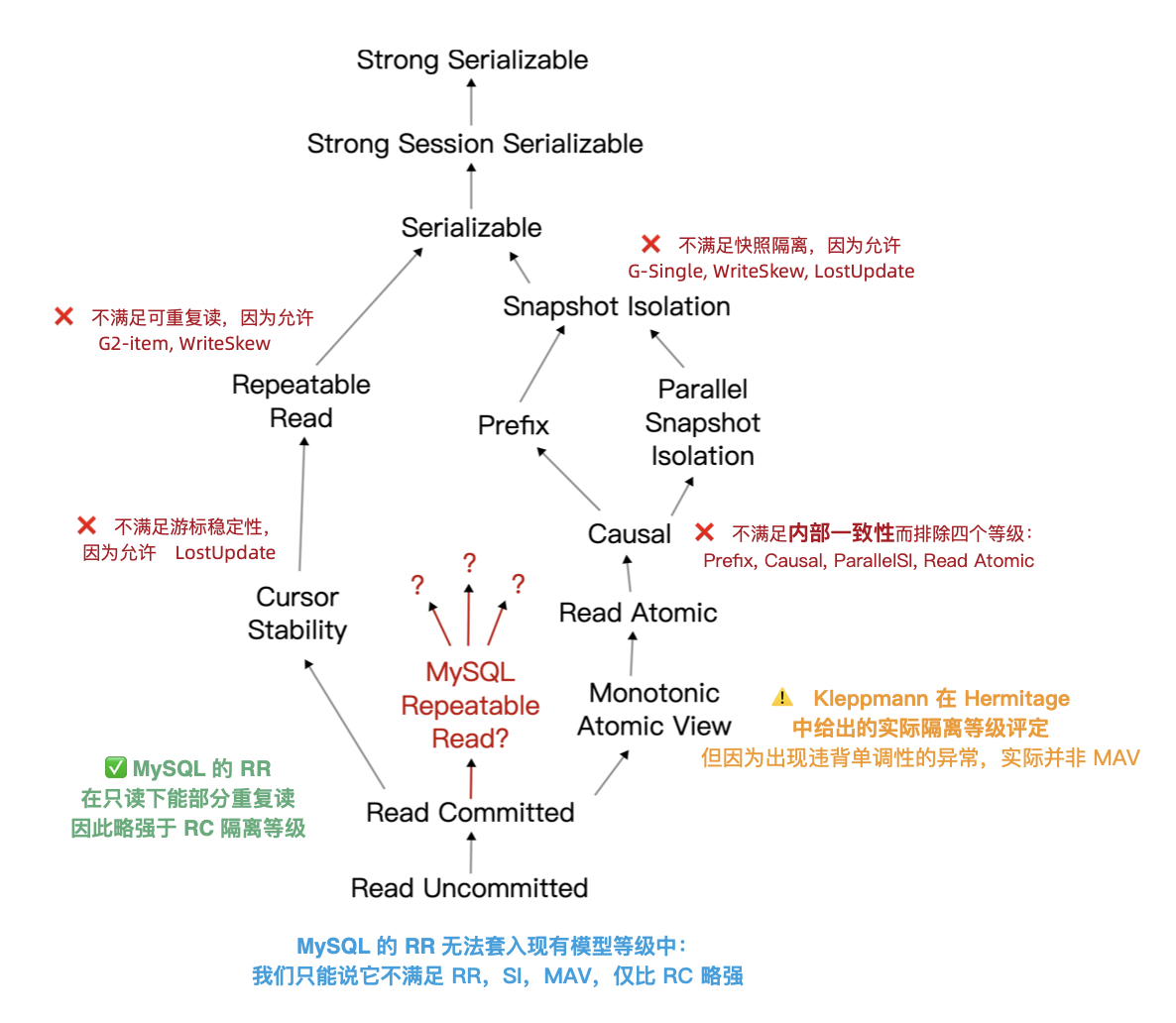

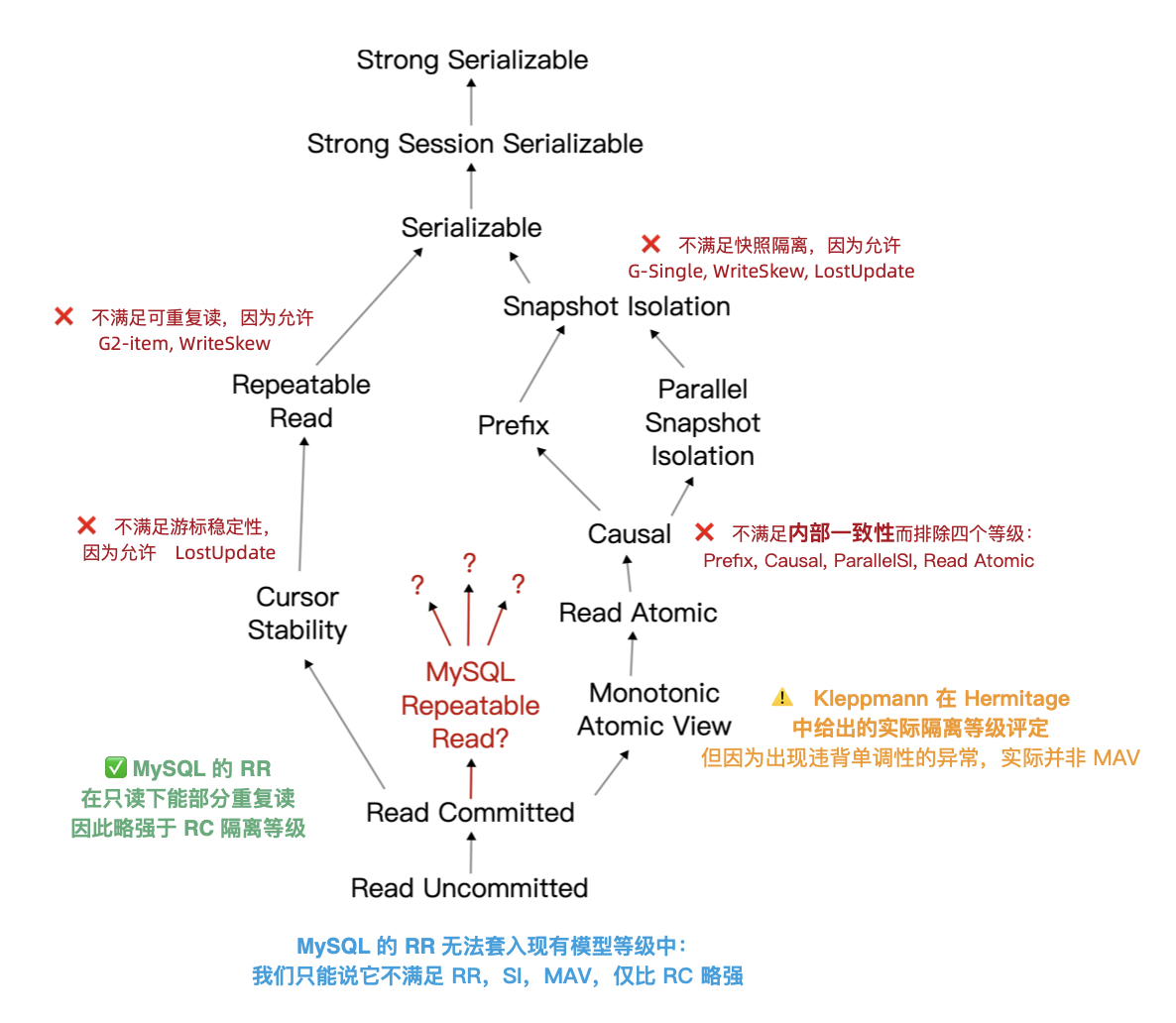

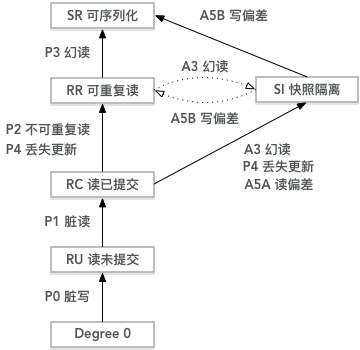

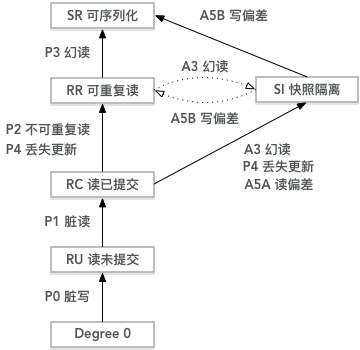

权威的分布式事务测试组织 JEPSEN 研究发现,MySQL 文档声称实现的 可重复读/RR 隔离等级,实际提供的正确性保证要弱得多 —— MySQL 8.0.34 默认使用的 RR 隔离等级实际上并不可重复读,甚至既不原子也不单调,连 单调原子视图/MAV 的基本水平都不满足。这意味着 MySQL 的 RR 隔离等级实际上还不如绝大多数 DBMS 的 RC 隔离等级(实际 MAV)。

MySQL 的 ACID 存在缺陷,且与文档承诺不符 —— 而轻信这一虚假承诺可能会导致严重的正确性问题,例如数据错漏与对账不平。对于一些数据完整性很关键的场景 —— 例如金融,这一点是无法容忍的。

此外,能“避免”这些异常的 MySQL 可串行化/SR 隔离等级难以生产实用,也非官方文档与社区认可的最佳实践;尽管专家开发者可以通过在查询中显式加锁来规避此类问题,但这样的行为极其影响性能,而且容易出现死锁。

与此同时,PostgreSQL 在 9.1 引入的 可串行化快照隔离(SSI) 算法可以用极小的性能代价提供完整可串行化隔离等级 —— 而且 PostgreSQL 的 SR 在正确性实现上毫无瑕疵 —— 这一点即使是 Oracle 也难以企及。

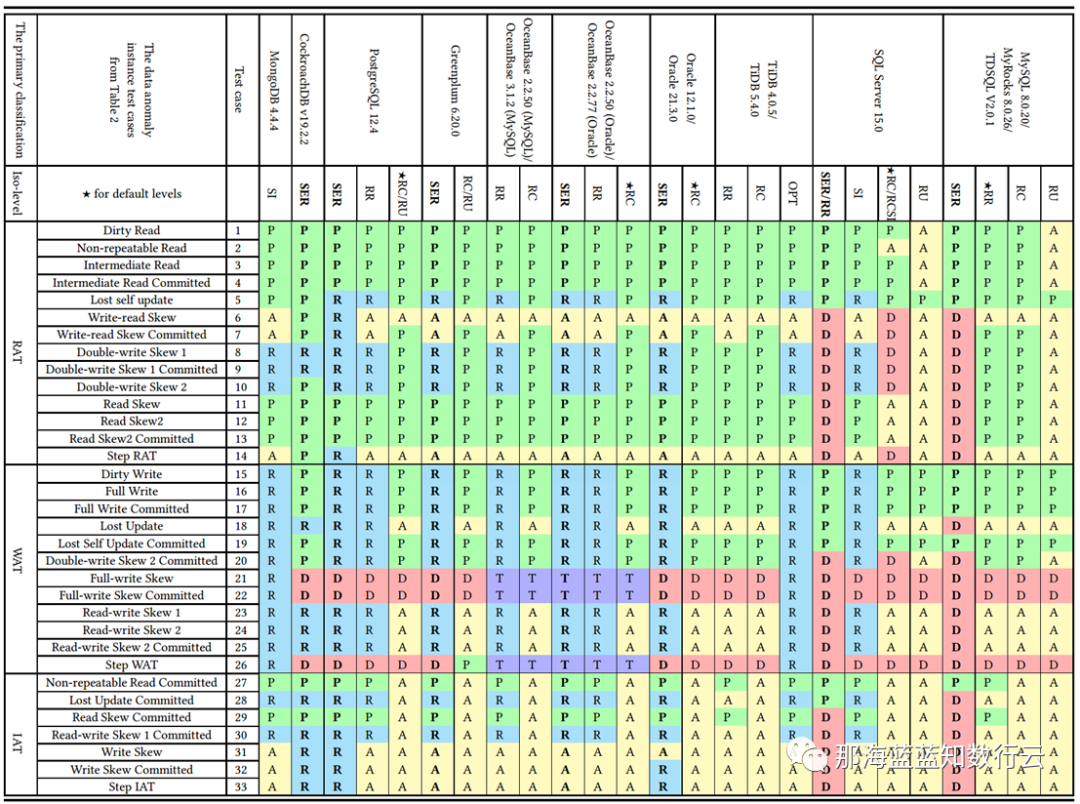

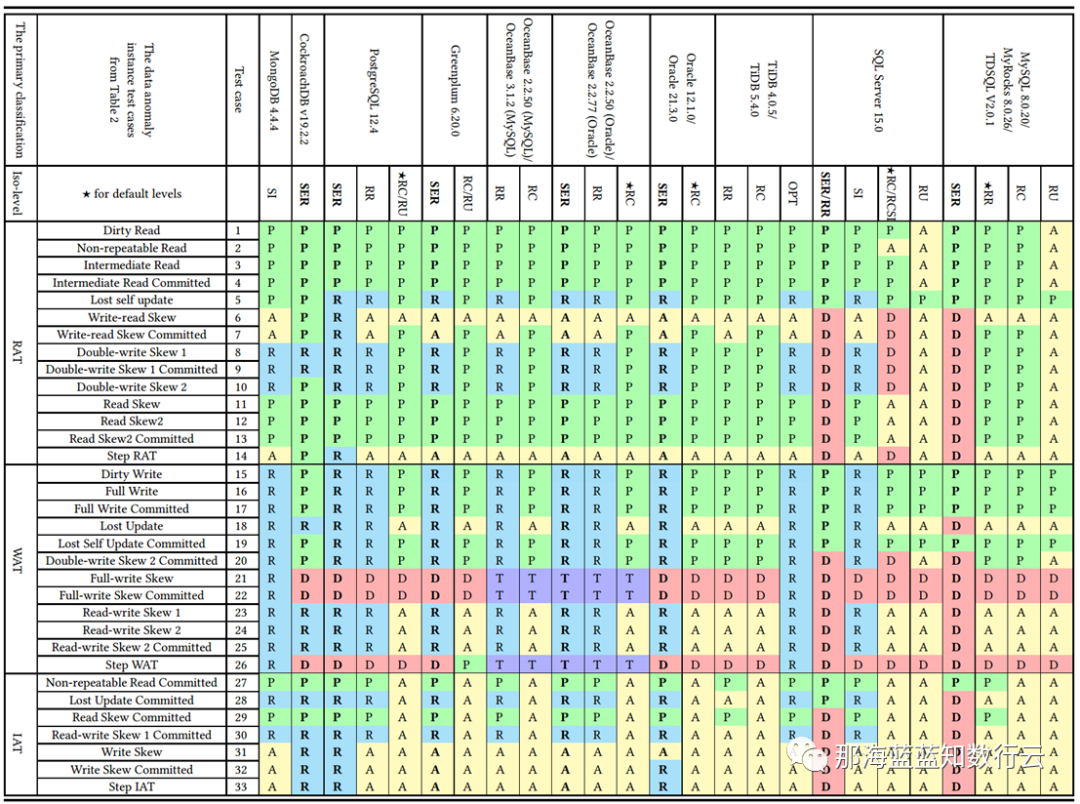

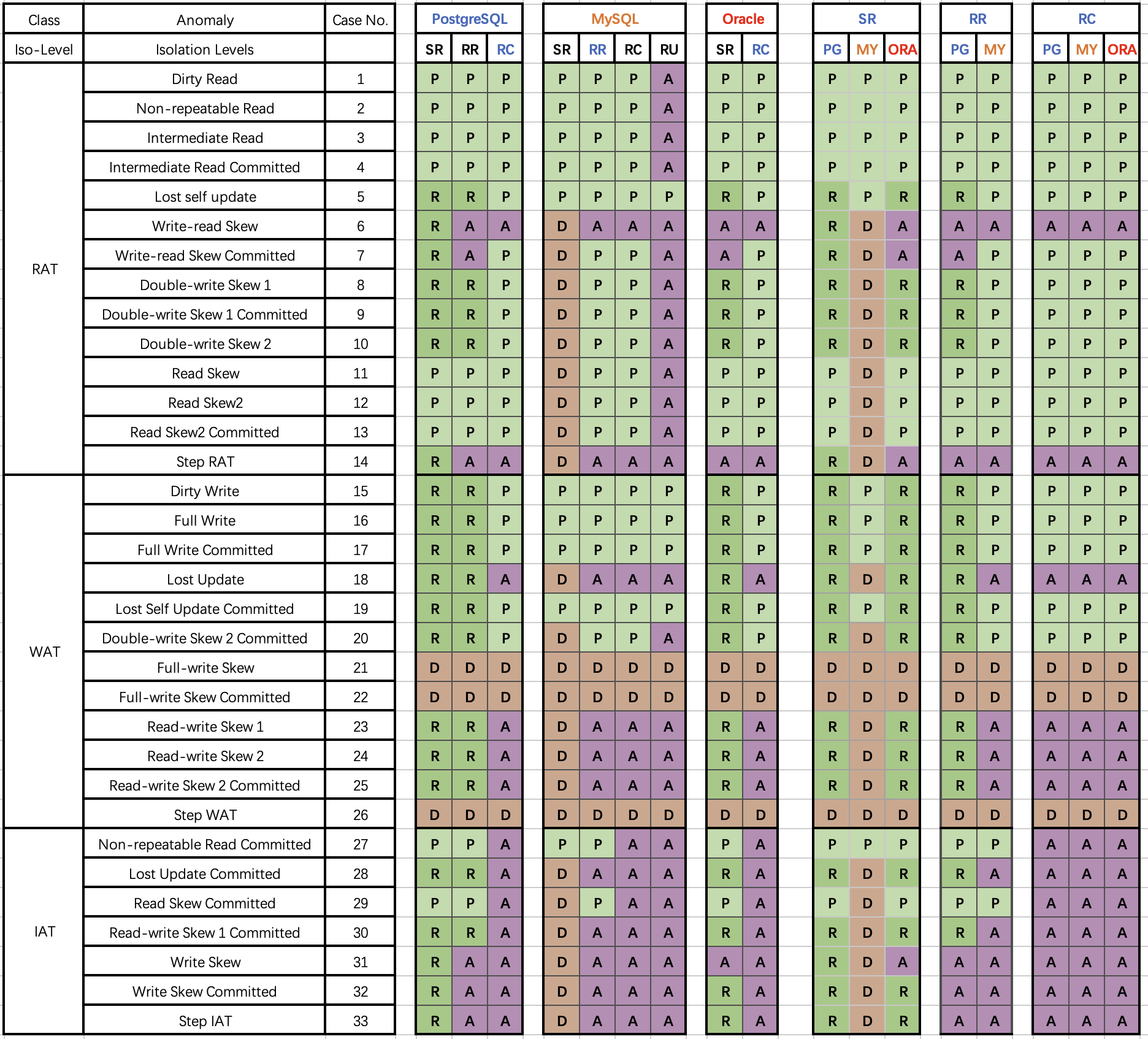

李海翔教授在《一致性八仙图》论文中,系统性地评估了主流 DBMS 隔离等级的正确性,图中蓝/绿色代表正确用规则/回滚避免异常;黄A代表异常,越多则正确性问题就越多;红“D”指使用了影响性能的死锁检测来处理异常,红D越多性能问题就越严重;

不难看出,这里正确性最好(无黄A)的实现是 PostgreSQL SR,与基于PG的 CockroachDB SR,其次是略有缺陷 Oracle SR;主要都是通过机制与规则避免并发异常;而 MySQL 出现了大面积的黄A与红D,正确性水平与实现手法糙地不忍直视。

做正确的事很重要,而正确性是不应该拿来做利弊权衡的。在这一点上,开源关系型数据库两巨头 MySQL 和 PostgreSQL 在早期实现上就选择了两条截然相反的道路: MySQL 追求性能而牺牲正确性;而学院派的 PostgreSQL 追求正确性而牺牲了性能。

在互联网风口上半场中,MySQL 因为性能优势占据先机乘风而起。但当性能不再是核心考量时,正确性就成为了 MySQL 的致命出血点。 更为可悲的是,MySQL 连牺牲正确性换来的性能,都已经不再占优了,这着实让人唏嘘不已。

完备性

SQL 特性与标准支持:PostgreSQL 一直以高度符合 SQL 标准著称,支持复杂查询、窗口函数、公共表表达式(CTE)、递归查询、完整的外键约束等功能,并且实现了丰富的 SQL/JSON 标准和自定义函数。 MySQL 过去在标准支持上相对落后,但自 8.0 版本起补齐了一些短板:如支持窗口函数和 CTE(包括递归 CTE)等,使其在查询特性上拉近了距离。 但是魔鬼在细节中,许多看上去 “你有我也有” 的功能,内在的实现水准是完全不一样的。

以 Ecoding 字符编码与 Collation 排序规则为例,这是很典型的企业级应用需要的多语言关键特性。PostgreSQL 在 ICU 支持下提供了 42 种字符集编码与 815 种排序规则支持,覆盖了几乎你能想象到的一切排序方法。 而 MySQL 在基本上就只有 五种字符集和几十个基于此的排序规则。这是一个很好的微观细节样本,体现出 PostgreSQL 与 MySQL 在细节上的用心程度与差异。

生态

对一项技术而言,用户的规模直接决定了生态的繁荣程度。瘦死的骆驼比马大,烂船也有三斤钉。 MySQL 曾经搭乘互联网东风扶摇而起,攒下了丰厚的家底,它的 Slogan 就很能说明问题 —— “世界上最流行的开源关系型数据库”。

开发者

MySQL 的 Slogan 是 “世界上最流行的开源关系型数据库”,但似乎现在并没有多少权威数据能支持这个说法。

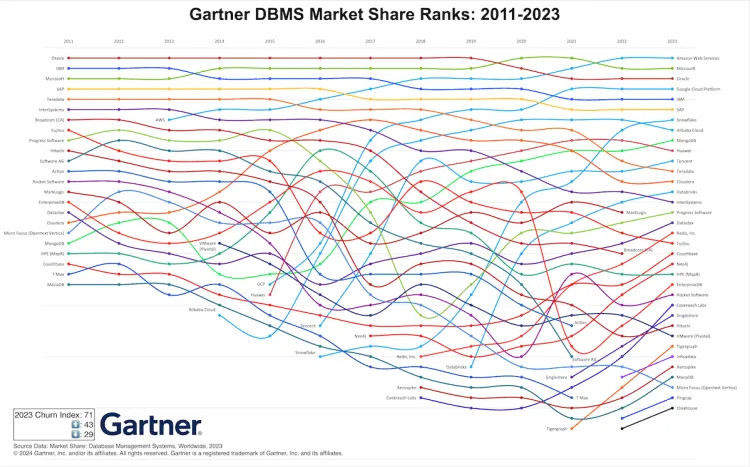

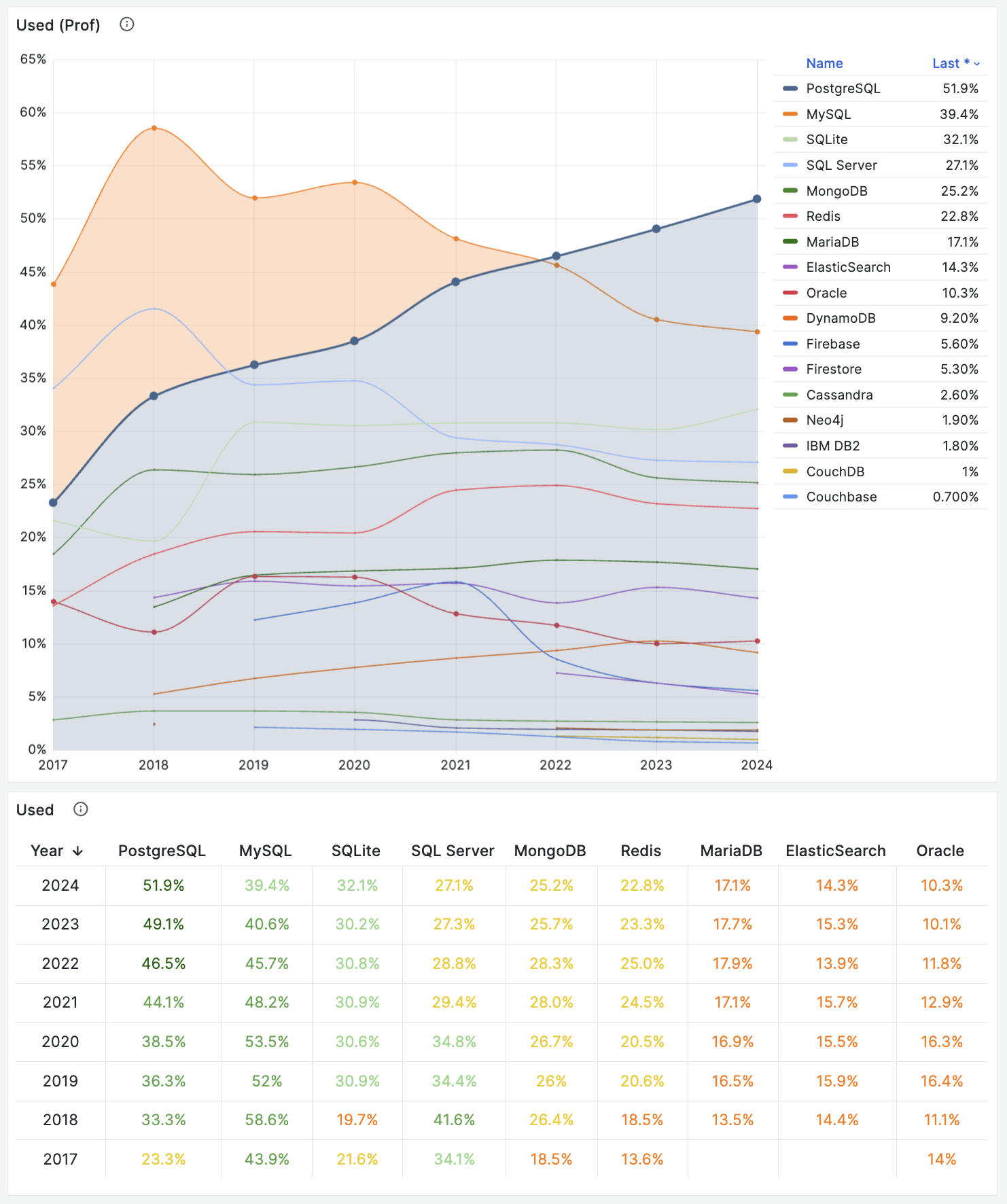

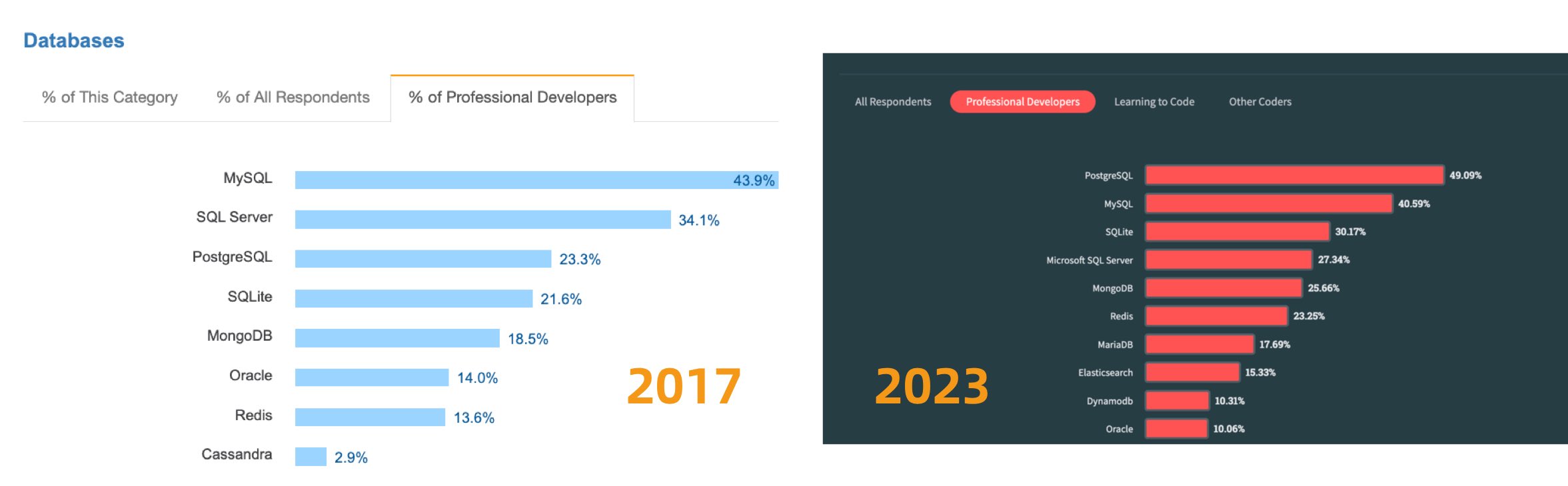

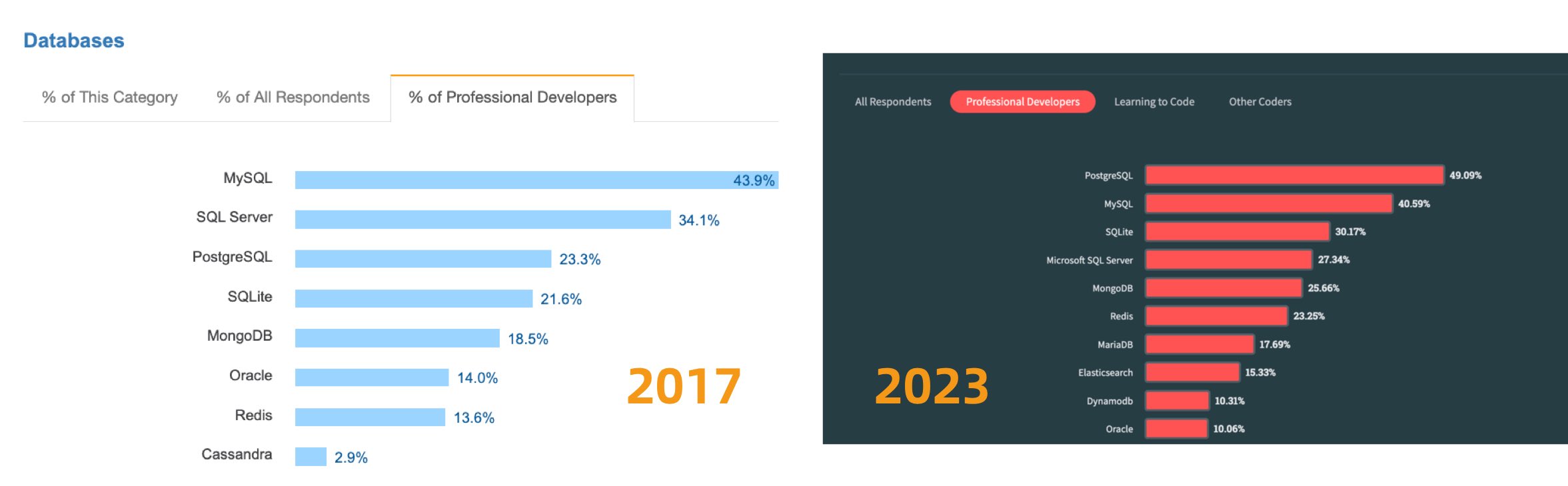

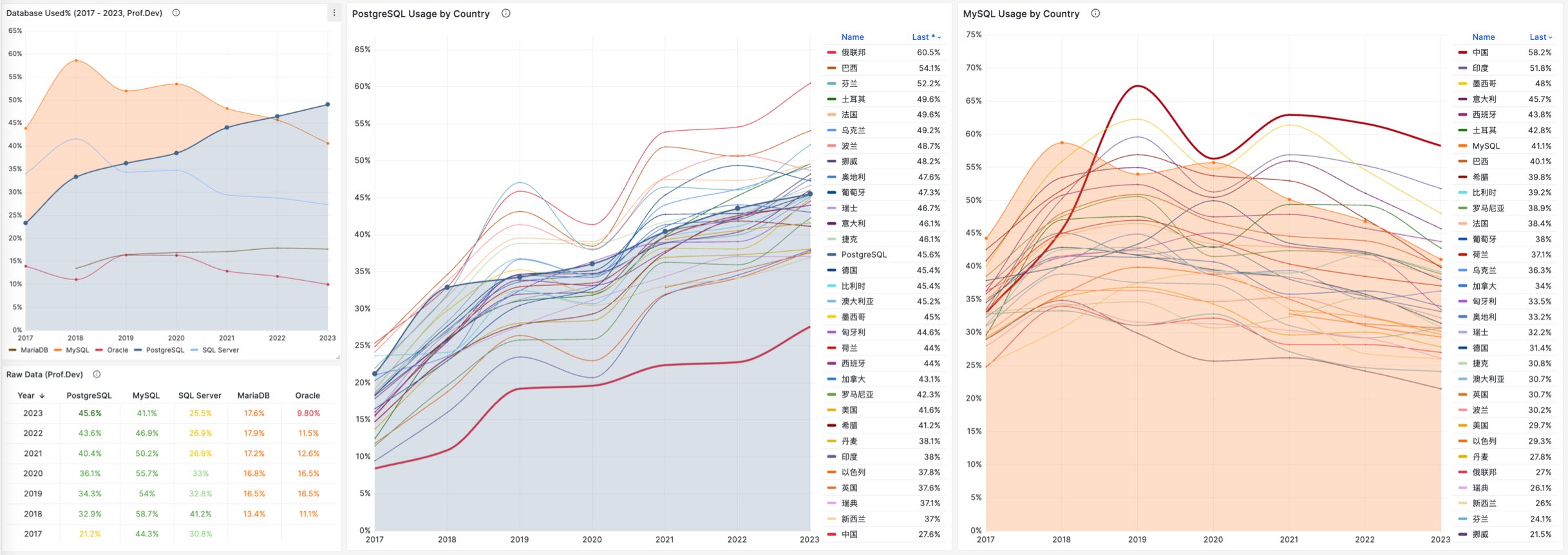

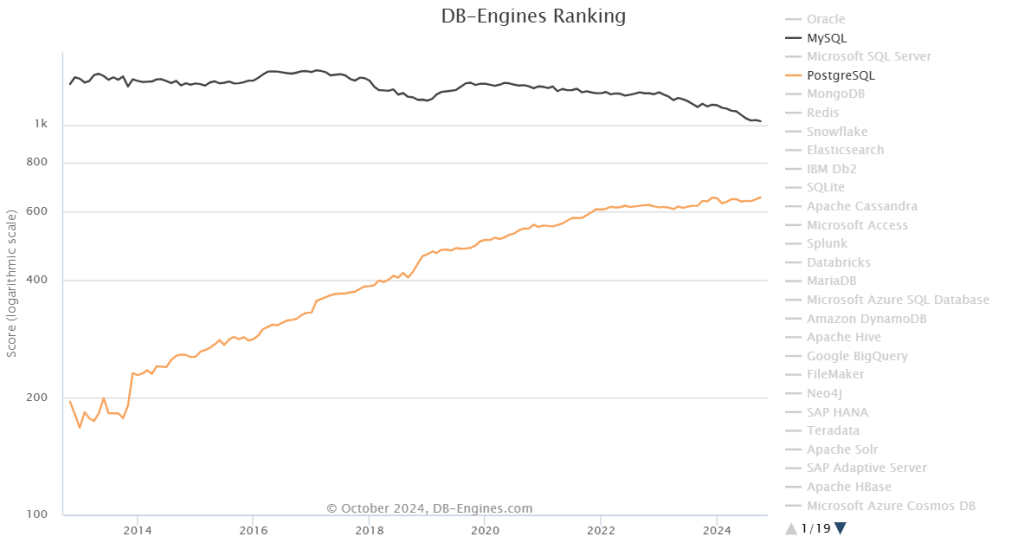

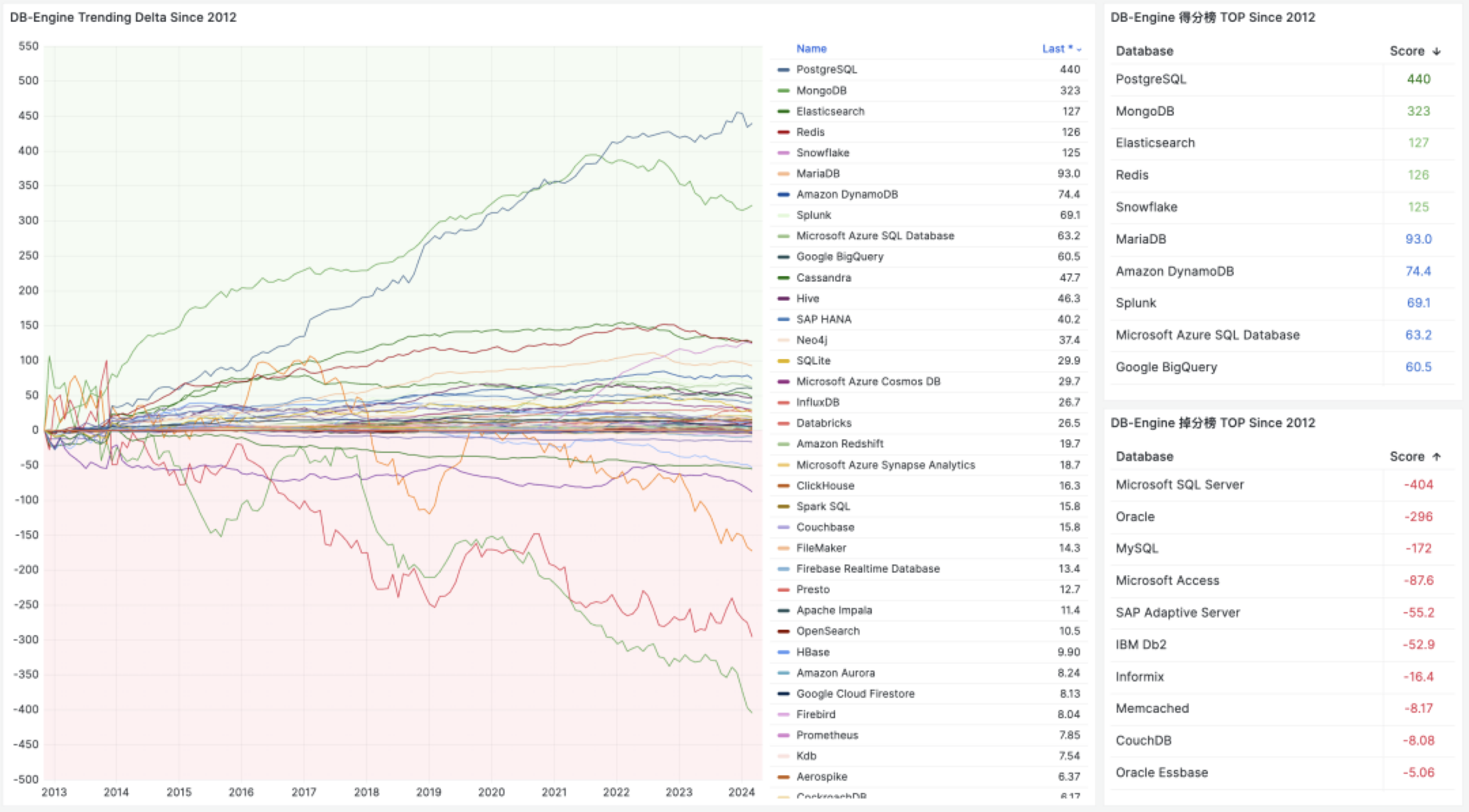

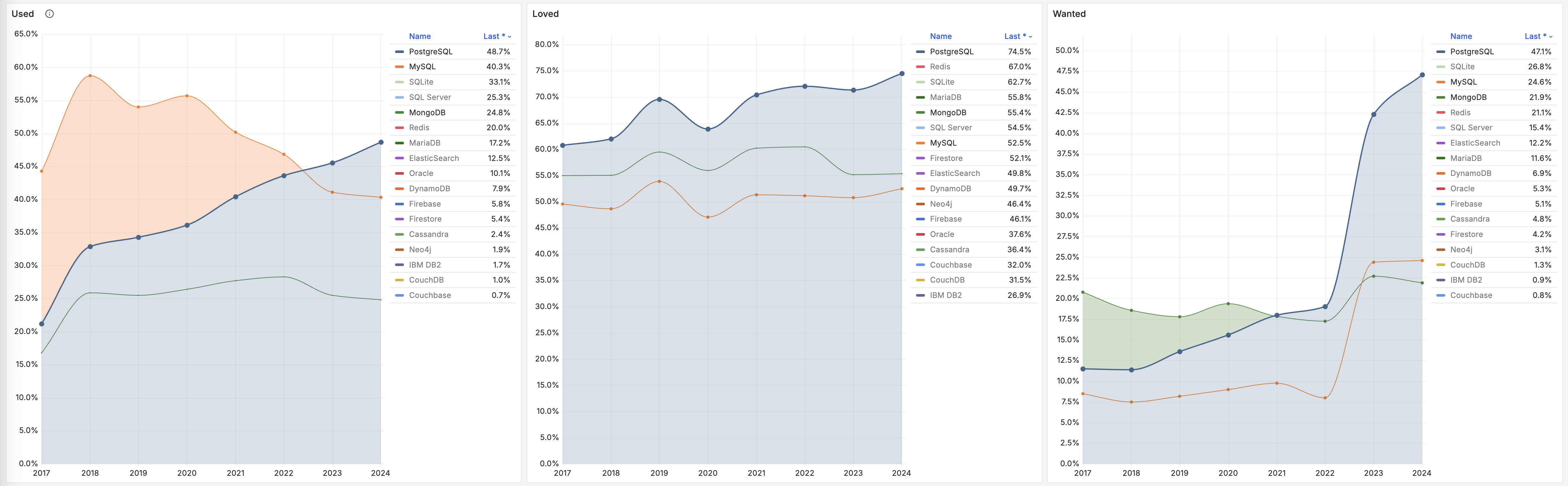

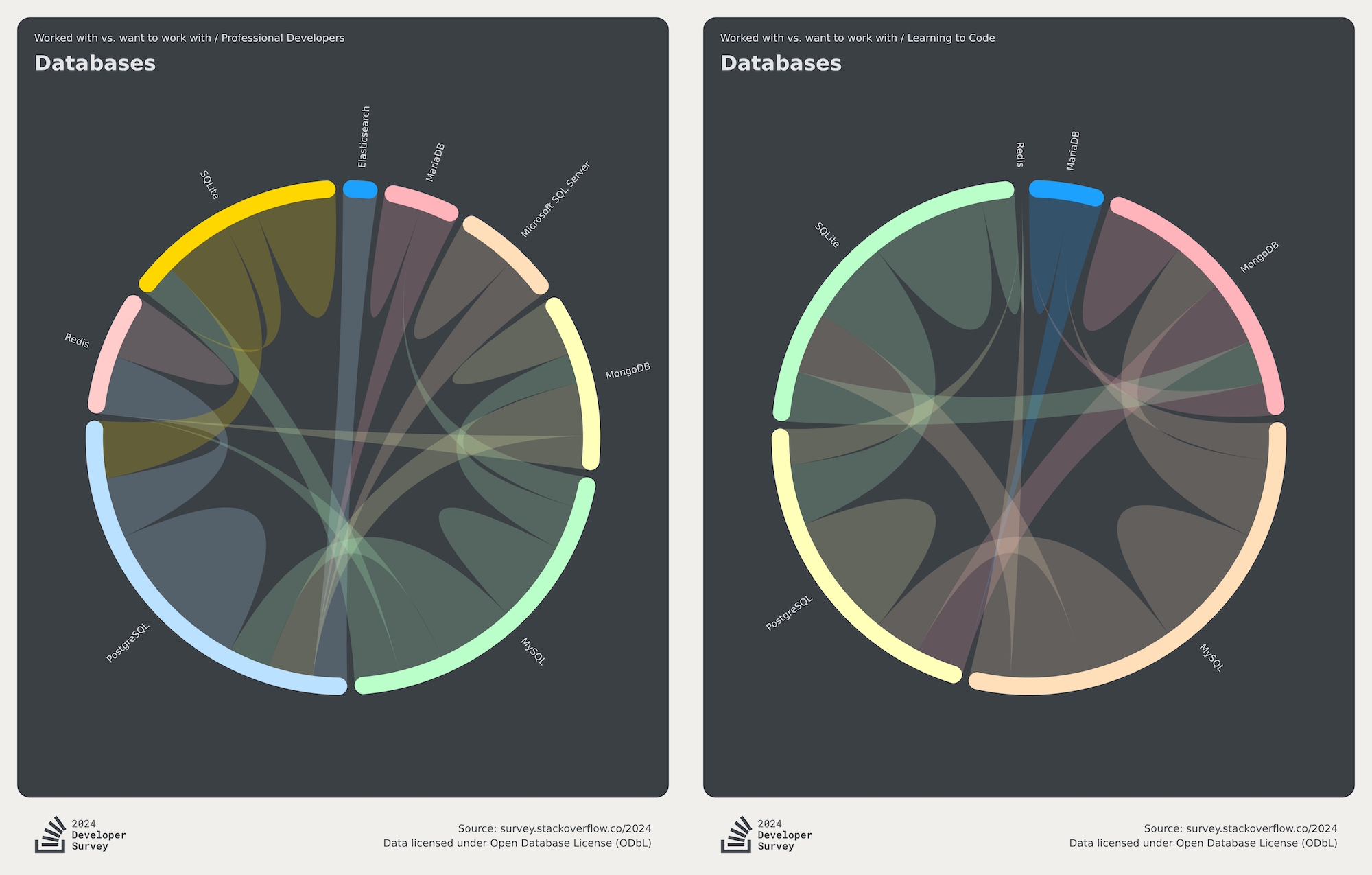

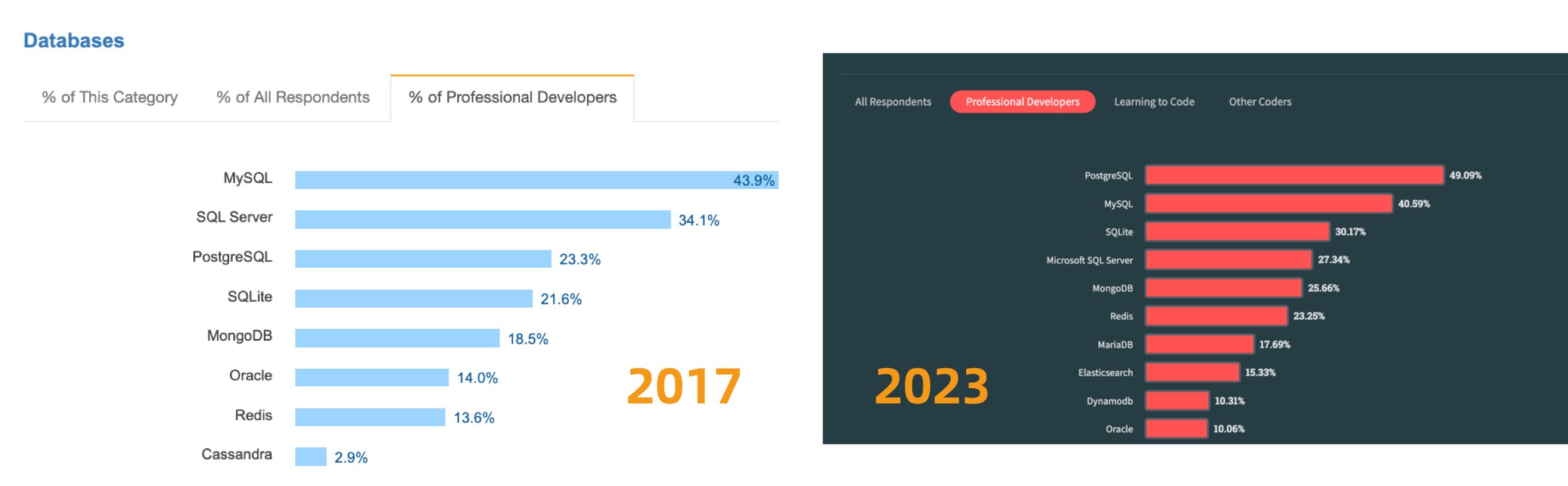

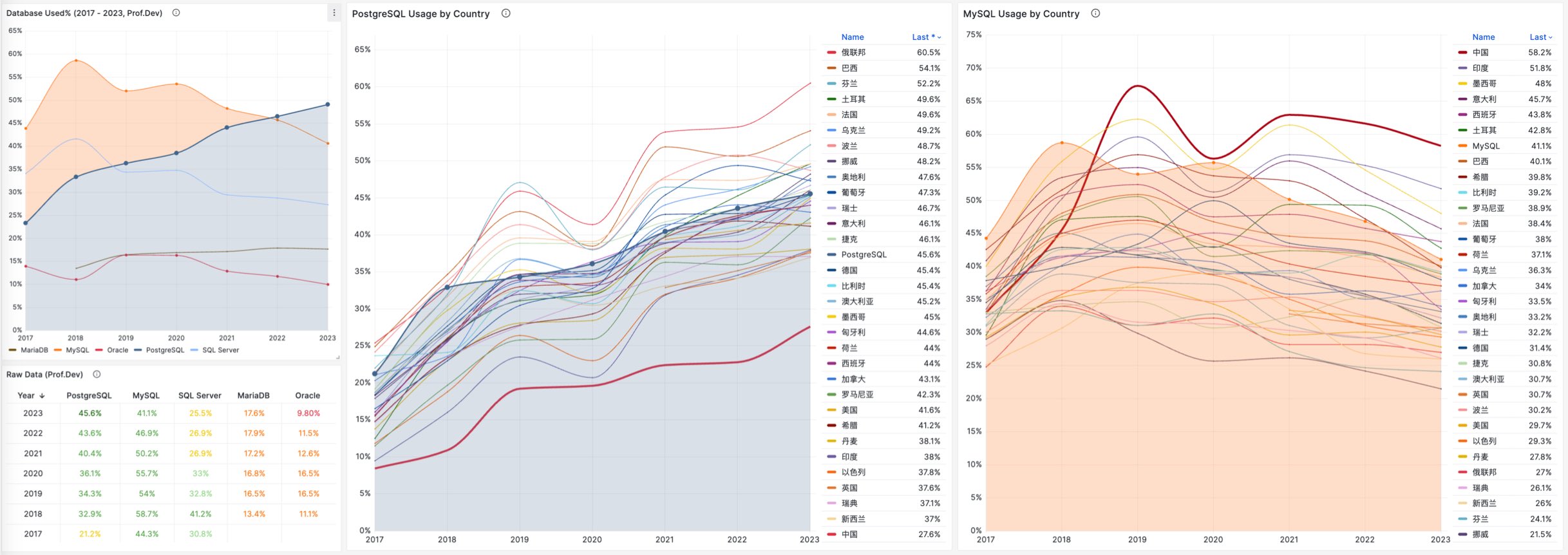

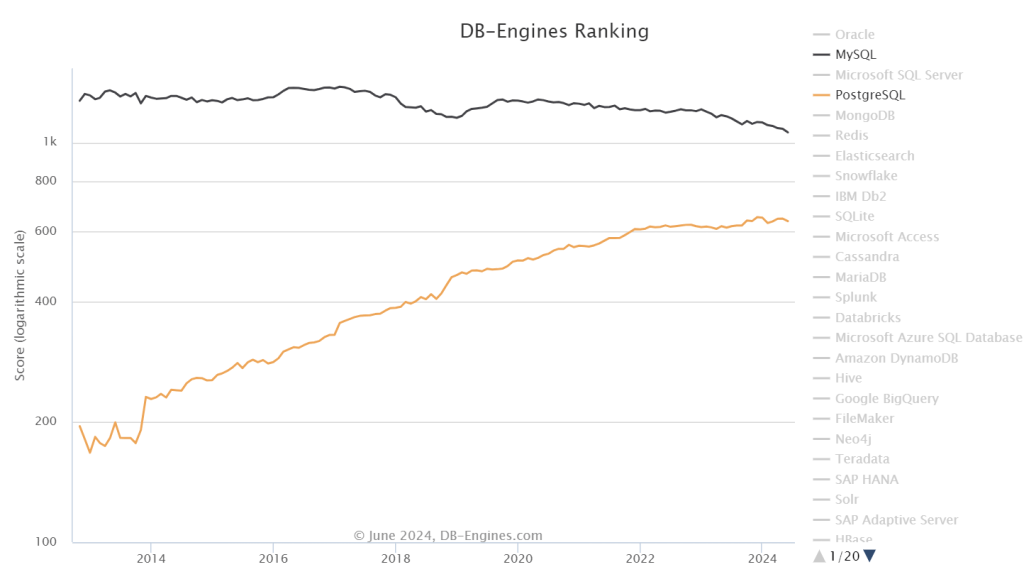

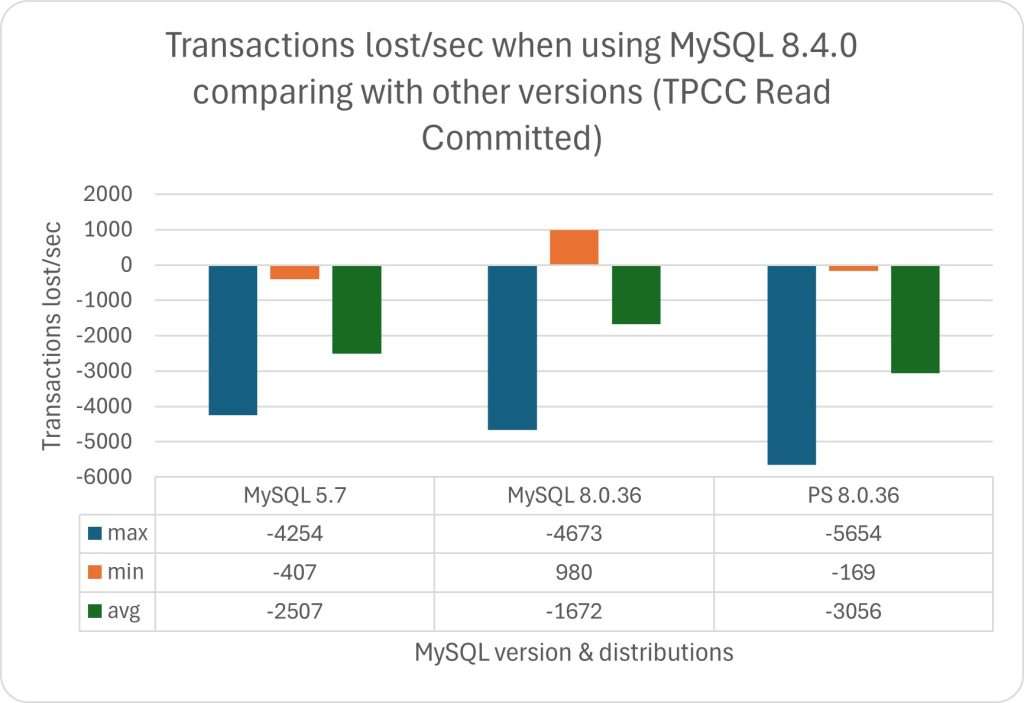

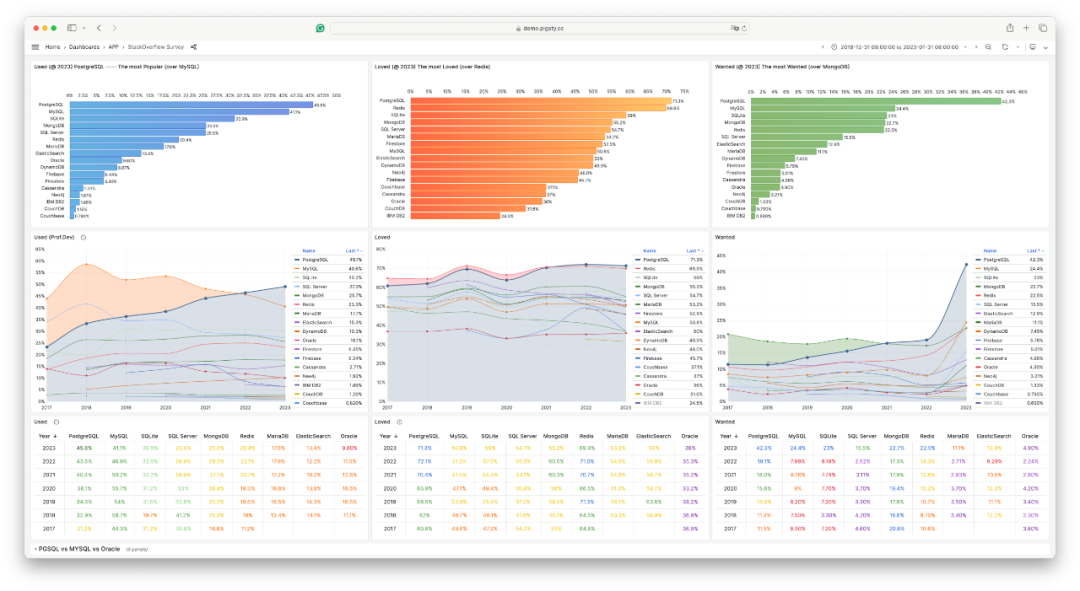

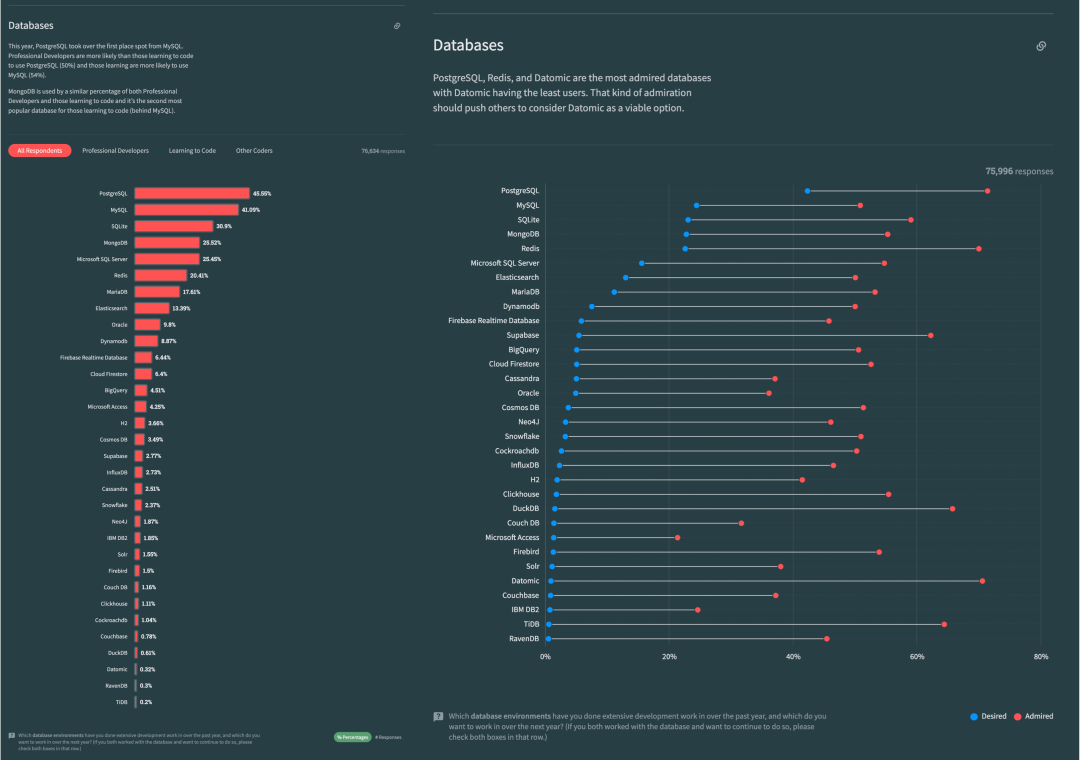

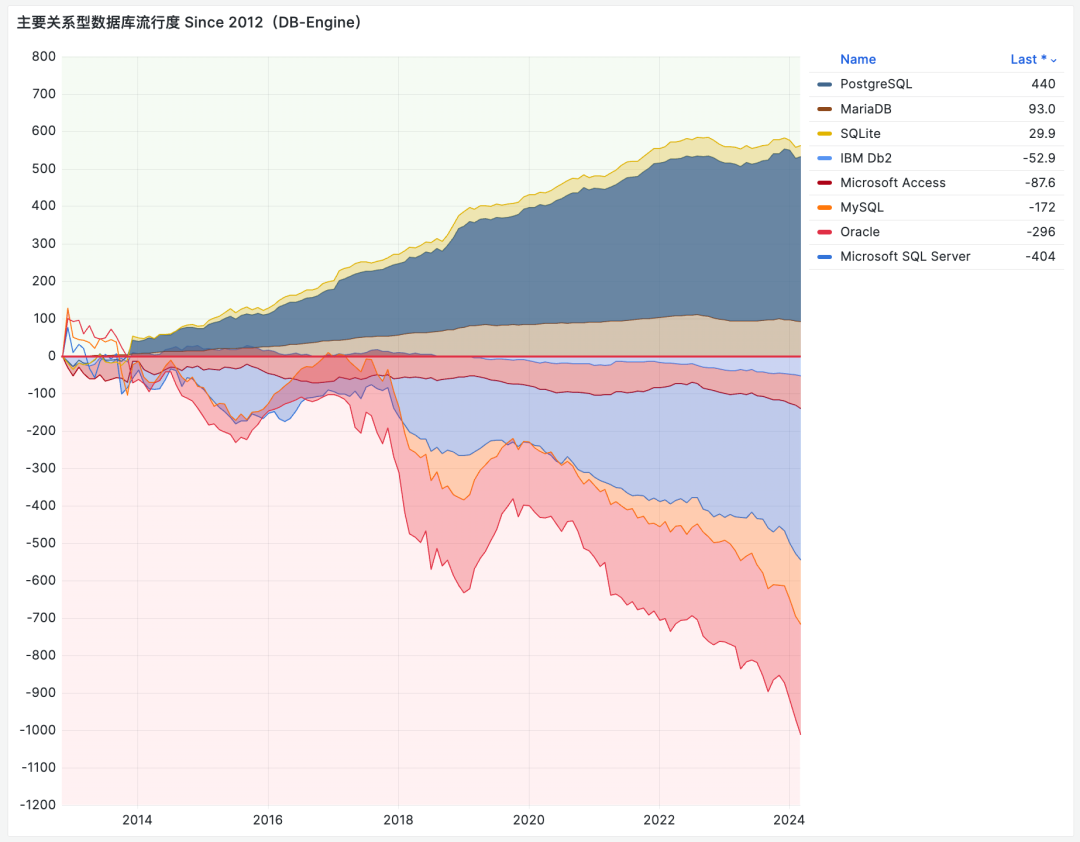

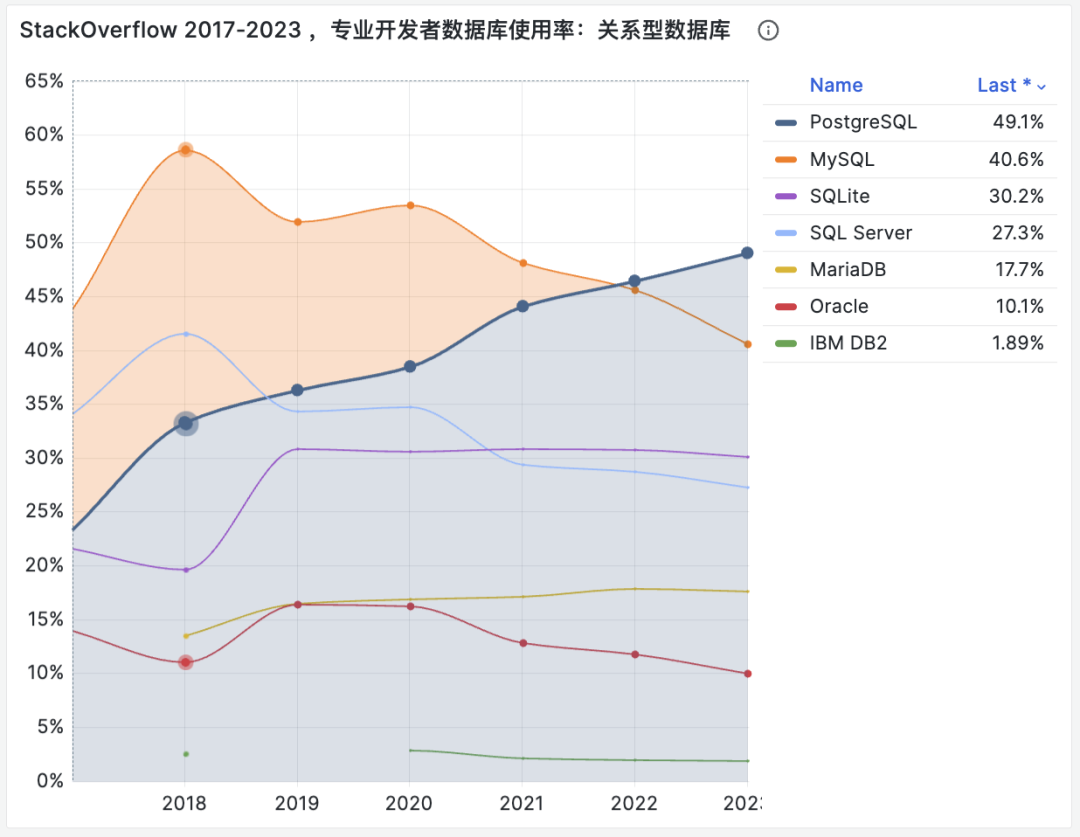

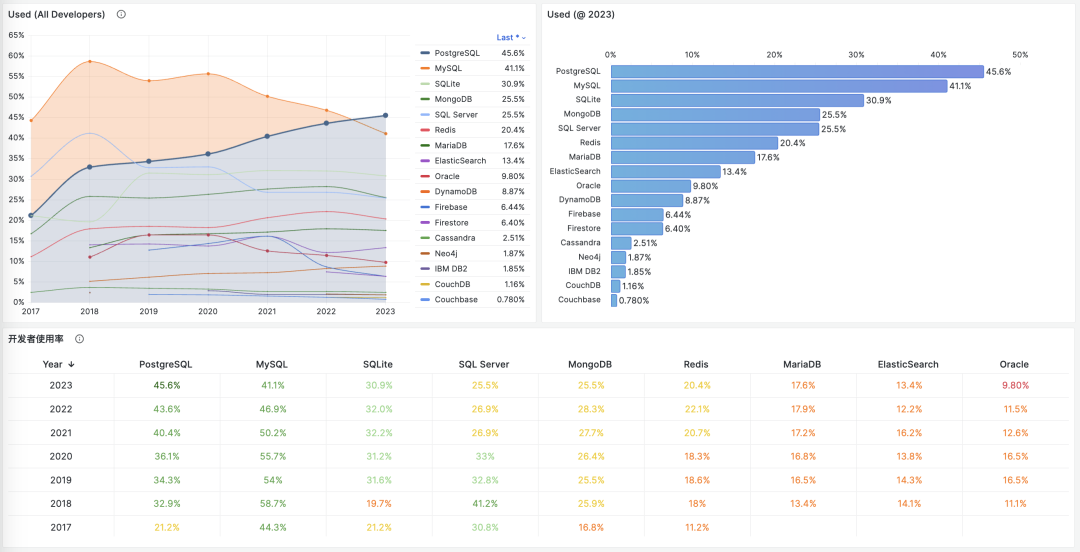

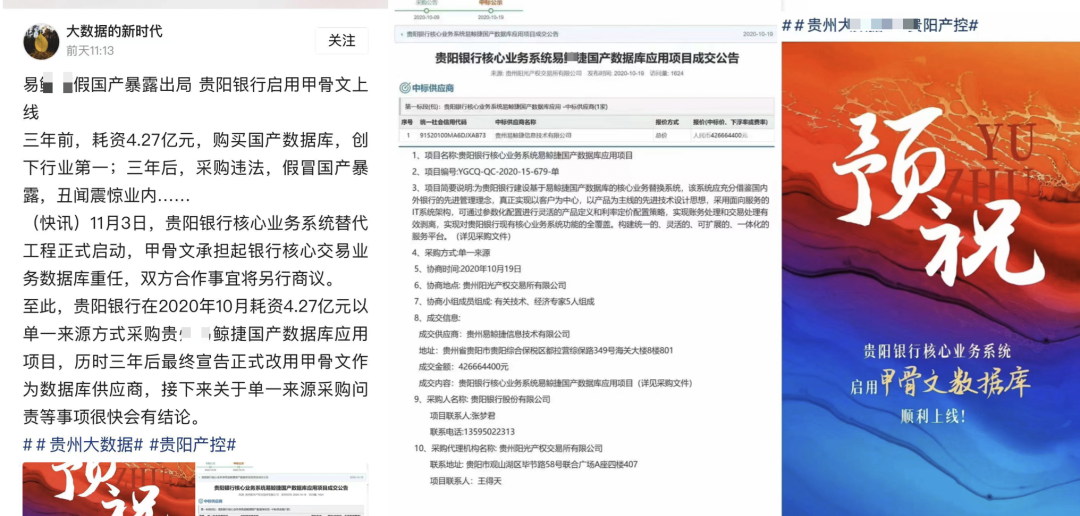

相反的是,在 StackOverflow 过去八年的全球开发者调研中,我们可以观察到 PostgreSQL 在开发者中的使用率节节攀升,并于 2023 年第一次超过 MySQL ,成为最流行的数据库。

从各个角度上来看,MySQL “最流行” 的称号已经名不副实了。而 PostgreSQL 已经成为这几年最流行的数据库,并且不需要不需要开源/关系型等定语修饰。

在最为活跃的前端开发者生态中,PostgreSQL 已经凭借丰富的功能特性,以压倒性优势成为最受欢迎的的数据库。

在 Vercel 支持的 7 款存储服务上,四个是 Postgres 衍生(Neon,Supabase,Nile,Gel),两个 Redis 衍生,一个 DuckDB ,完全不见 MySQL 的踪影。

而根据 DBDB.io 的统计数据,派生自 PostgreSQL 的数据库项目也显著超过了 MySQL。

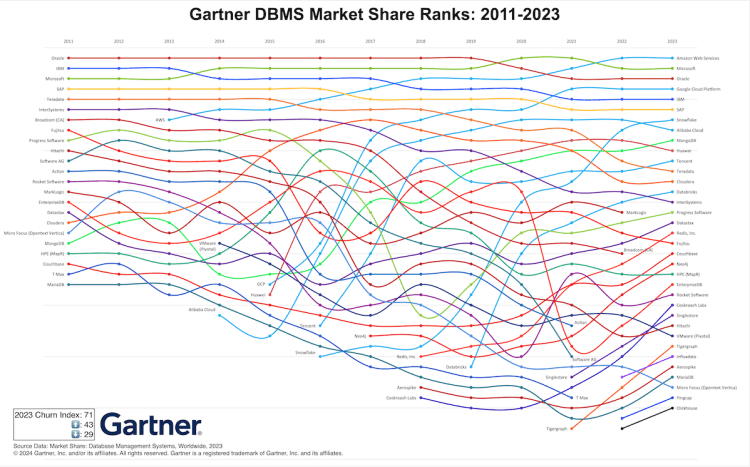

厂商

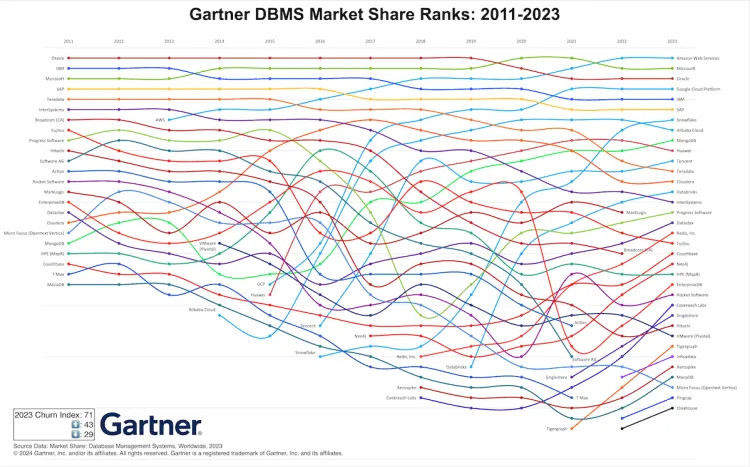

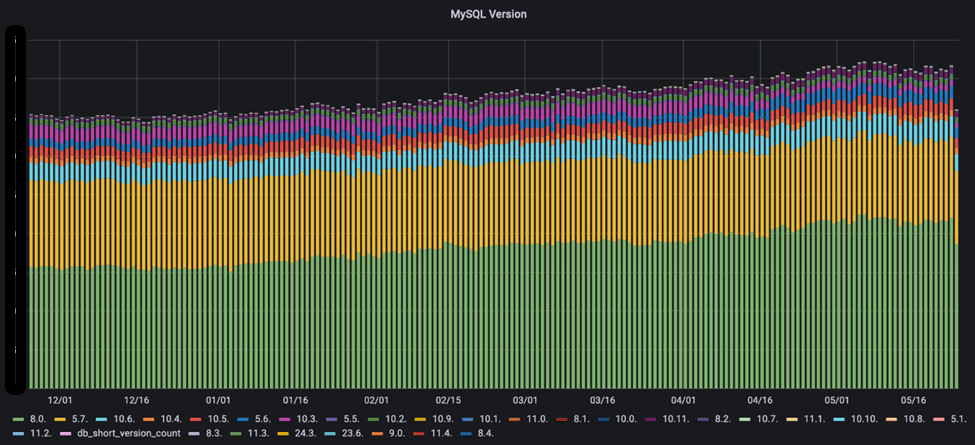

最直观的数据: AWS RDS 上 PostgreSQL 实例的数量与 MySQL 实例的数量已经达到了 6:4 ,也就是 PG 实例的数量已经比 MySQL 要多 50% 了。 详情参考:《PostgreSQL取得对MYSQL的压倒性优势》

即使是在 MYSQL 曾经占据压倒性优势的中国大陆,来自阿里云 RDS 实例数的样本也说明 MYSQL:PG 从前几年的 10:1 快速缩小到 5:1,并且增量上 PG 也已经超过 MYSQL 了。

从商业角度看,云厂商已经将重注下在了 PostgreSQL,而非 MySQL 上。 例如 AWS RDS (MySQL+PG)产品经理是 PostgreSQL 社区核心组成员 Jonathan Katz,也是最近 pg/pgvector 在向量数据库领域崛起关键推手之一。

最近的 Aurora 新品分布式 DSQL 只有 PostgreSQL 兼容,没搞 MySQL 的,而以前这种事从来都是 MySQL 优先,这次似乎直接放弃 MYSQL 支持了。 Google 的 OLTP 数据库 AlloyDB 也选择完全兼容 PostgreSQL ,并且也在 Spanner 中提供 PostgreSQL 了。 国内云厂商例如阿里云也选择押宝 PostgreSQL 分支路线,例如获得信创资质认证的 PolarDB 2.0 (Oracle)兼容其实就是基于 PolarDB PG 二次分枝的版本。

资本市场

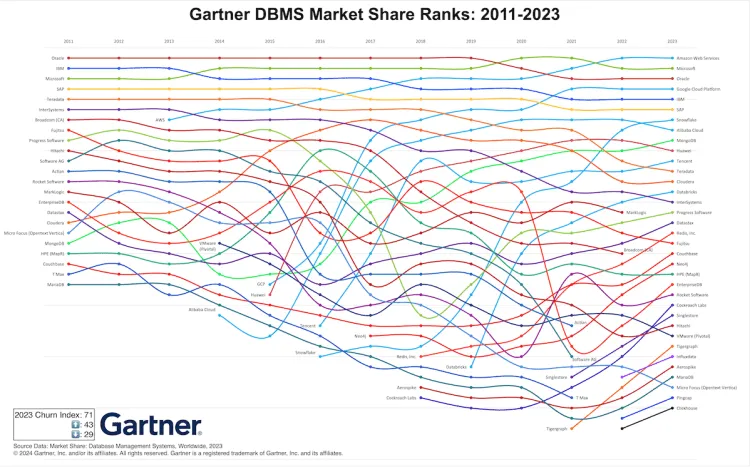

最近的 大额融资纪录,也基本发生在 PostgreSQL 生态中。

而 MySQL 生态屈指可数,基本只有 SingleStore,TiDB ,而原本生态中全村的希望 MariaDB 则一路跌的干脆直接要退市私有化了。

大型用例

对于制造业,金融,非互联网场景,PostgreSQL 凭借其强大的功能特性与正确性,已经成为了许多大型企业的首选数据库。

例如在我任职 Apple 期间,我们部门使用 PostgreSQL 存储所有工厂的工业互联网数据并进行数据分析。包括我们部门在内的许多项目都在使用 PostgreSQL,甚至有一个内部的社区与兴趣小组。

大型互联网公司受制于历史路径依赖于惯性仍然保留有大量 MySQL,但在新兴创业公司中,PostgreSQL 已经取得显著优势。 例如,Cursor、 Dify、Notion 这样的 AI 新宠都默认使用 PostgreSQL 作为元数据存储。支付明星企业 Strip 也在一些系统中使用 PostgreSQL 进行分析。

Cloudflare 与 Vercel 的内部系统大量使用了 PostgreSQL, Node.js 社区项目也明显对 PostgreSQL 有偏好(例如 Prisma ORM 对PG 支持更完善)

MYSQL 到底怎么了?

究竟是谁杀死了 MySQL,难道是 PostgreSQL 吗?Peter Zaitsev 在《Oracle最终还是杀死了MySQL》一文中控诉 —— Oracle 的不作为与瞎指挥最终害死了 MySQL;并在后续《Oracle还能挽救MySQL吗》一文中指出了真正的根因:

MySQL 的知识产权被 Oracle 所拥有,它不是像 PostgreSQL 那种 “由社区拥有和管理” 的数据库,也没有 PostgreSQL 那样广泛的独立公司贡献者。不论是 MySQL 还是其分叉 MariaDB,它们都不是真正意义上像 Linux,PostgreSQL,Kubernetes 这样由社区驱动的的原教旨纯血开源项目,而是由单一商业公司主导。

比起向一个商业竞争对手贡献代码,白嫖竞争对手的代码也许是更为明智的选择 —— AWS 和其他云厂商利用 MySQL 内核参与数据库领域的竞争,却不回馈任何贡献。于是作为竞争对手的 Oracle 也不愿意再去管理好 MySQL,而干脆自己也参与进来搞云 —— 仅仅只关注它自己的 MySQL heatwave 云版本,就像 AWS 仅仅专注于其 RDS 管控和 Aurora 服务一样。在 MySQL 社区凋零的问题上,云厂商也难辞其咎。

总结

尽管我是 PostgreSQL 的坚定支持者,但我也赞同 Peter Zaitsev 的观点:“如果 MySQL 彻底死掉了,开源关系型数据库实际上就被 PostgreSQL 一家垄断了,而垄断并不是一件好事,因为它会导致发展停滞与创新减缓。PostgreSQL 要想进入全盛状态,有一个 MySQL 作为竞争对手并不是坏事”

至少,MySQL 可以作为一个鞭策激励,让 PostgreSQL 社区保持凝聚力与危机感,不断提高自身的技术水平,并继续保持开放、透明、公正的社区治理模式,从而持续推动数据库技术的发展。

MySQL 曾经也辉煌过,也曾经是“开源软件”的一杆标杆,但再精彩的演出也会落幕。MySQL 正在死去 —— 更新疲软,功能落后,性能劣化,质量出血,生态萎缩,此乃天命,实非人力所能改变。而 PostgreSQL ,将带着开源软件的初心与愿景继续坚定前进 —— 它将继续走 MySQL 未走完的长路,写 MySQL 未写完的诗篇。

MySQL 的创新版正在逐渐失去它的意义,德哥看后写了 MySQL将保持平庸。 对于 MySQL 的 “创新版本”,Percona 的老板 Peter Zaitsev 也发三篇《MySQL将何去何从》,《Oracle最终还是杀死了MySQL》,《Oracle还能挽救MySQL吗》,公开表达了对 MySQL 的失望与沮丧。沮丧;

与此同时,MySQL 的生态正在不断萎缩,由于 MYSQL 属于 Oracle,其他生态参与者越来越没有兴趣为 Oracle 做贡献,Oracle 也将心思放在 了 MySQL 企业版上,导致 MySQL 的开源社区越来越小,越来越没有活力。 例如,最近的 MySQL 9.x “创新版本” 被社区评价为毫无诚意的平庸之作。

例如 MySQL 开源生态的关键参与者 Percona 老板 Peter Zaitsev 也Percona 的老板 Peter Zaitsev 也发三篇《MySQL将何去何从》,《Oracle最终还是杀死了MySQL》,《Oracle还能挽救MySQL吗》,公开表达了对 MySQL 的失望与沮丧。沮丧;

其实从 AWS 的产品发布与技术投入路线来看,不难看出全球云计算一哥已经把重注都下在了 PostgreSQL 上,首先整个 RDS (MySQL + PGSQL)的产品经理就是 PostgreSQL 社区核心组成员 Jonathan Katz ,近两年 PG/PGVECTOR 在向量数据库领域嘎嘎乱杀,背后的主要推手和贡献者就是 AWS。

对一项技术而言,用户的规模直接决定了生态的繁荣程度。瘦死的骆驼比马大,烂船也有三斤钉。 MySQL 曾经搭乘互联网东风扶摇而起,攒下了丰厚的家底,它的 Slogan 就很能说明问题 —— “世界上最流行的开源关系型数据库”。

不幸地是在 2023 年,至少根据全世界最权威的开发者调研之一的 StackOverflow Annual Developer Survey 结果来看,MySQL 的使用率已经被 PostgreSQL 反超了 —— 最流行数据库的桂冠已经被 PostgreSQL 摘取。

特别是,如果将过去七年的调研数据放在一起,就可以得到这幅 PostgreSQL / MySQL 在专业开发者中使用率的变化趋势图(左上) —— 在横向可比的同一标准下,PostgreSQL 流行与 MySQL 过气的趋势显得一目了然。

对于中国来说,此消彼长的变化趋势也同样成立。但如果对中国开发者说 PostgreSQL 比 MySQL 更流行,那确实是违反直觉与事实的。

将 StackOverflow 专业开发者按照国家细分,不难看出在主要国家中(样本数 > 600 的 31 个国家),中国的 MySQL 使用率是最高的 —— 58.2% ,而 PG 的使用率则是最低的 —— 仅为 27.6%,MySQL 用户几乎是 PG 用户的一倍。

与之恰好反过来的另一个极端是真正遭受国际制裁的俄联邦:由开源社区运营,不受单一主体公司控制的 PostgreSQL 成为了俄罗斯的数据库大救星 —— 其 PG 使用率以 60.5% 高居榜首,是其 MySQL 使用率 27% 的两倍。

中国因为同样的自主可控信创逻辑,最近几年 PostgreSQL 的使用率也出现了显著跃升 —— PG 的使用率翻了三倍,而 PG 与 MySQL 用户比例已经从六七年前的 5:1 ,到三年前的3:1,再迅速发展到现在的 2:1,相信会在未来几年内会很快追平并反超世界平均水平。 毕竟,有这么多的国产数据库,都是基于 PostgreSQL 打造而成 —— 如果你做政企信创生意,那么大概率已经在用 PostgreSQL 了。

抛开政治因素,用户选择使用一款数据库与否,核心考量还是质量、安全、效率、成本等各个方面是否“先进”。先进的因会反映为流行的果,流行的东西因为落后而过气,而先进的东西会因为先进变得流行,没有“先进”打底,再“流行”也难以长久。

如果你还在使用 MYSQL 准备做一些与数据库有关的新业务,是时候更新一下认知

都已经被 PostgreSQL 拉开了差距,而且这个差距还在进一步扩大中。

昨天,MySQL 发布了 “创新版本” 9.3 但是看上去和先前的 9.x 一样,都是些修修补补,看不到什么创新的东西。

MySQL 老司机丁奇看完 ReleaseNote 之后表示,MySQL 的创新版正在逐渐失去它的意义,德哥看后写了 MySQL将保持平庸。 对于 MySQL 的 “创新版本”,Percona 的老板 Peter Zaitsev 也发三篇《MySQL将何去何从》,《Oracle最终还是杀死了MySQL》,《Oracle还能挽救MySQL吗》,公开表达了对 MySQL 的失望与沮丧。沮丧;

然而和先前的几个版本一样,依然

PostgreSQL 正在高歌猛进,而 MySQL 却日薄西山,作为 MySQL 生态主要扛旗者的 Percona 也不得不悲痛地承认这一现实,连发三篇《MySQL将何去何从》,《Oracle最终还是杀死了MySQL》,《Oracle还能挽救MySQL吗》,公开表达了对 MySQL 的失望与沮丧;

Percona 的 CEO Peter Zaitsev 也表示:

有了 PostgreSQL,谁还需要 MySQL 呢? —— 但如果 MySQL 死了,PostgreSQL 就真的垄断数据库世界了,所以 MySQL 至少还可以作为 PostgreSQL 的磨刀石,让 PG 进入全盛状态。

有的数据库正在吞噬数据库世界,而有的数据库正在黯然地凋零死去。

MySQL is dead,Long live PostgreSQL!

空洞无物的创新版本

MySQL 官网发布的 “What’s New in MySQL 9.0” 介绍了 9.0 版本引入的几个新特性,而 MySQL 9.0 新功能概览 一文对此做了扼要的总结:

然后呢?就这些吗?这就没了!?

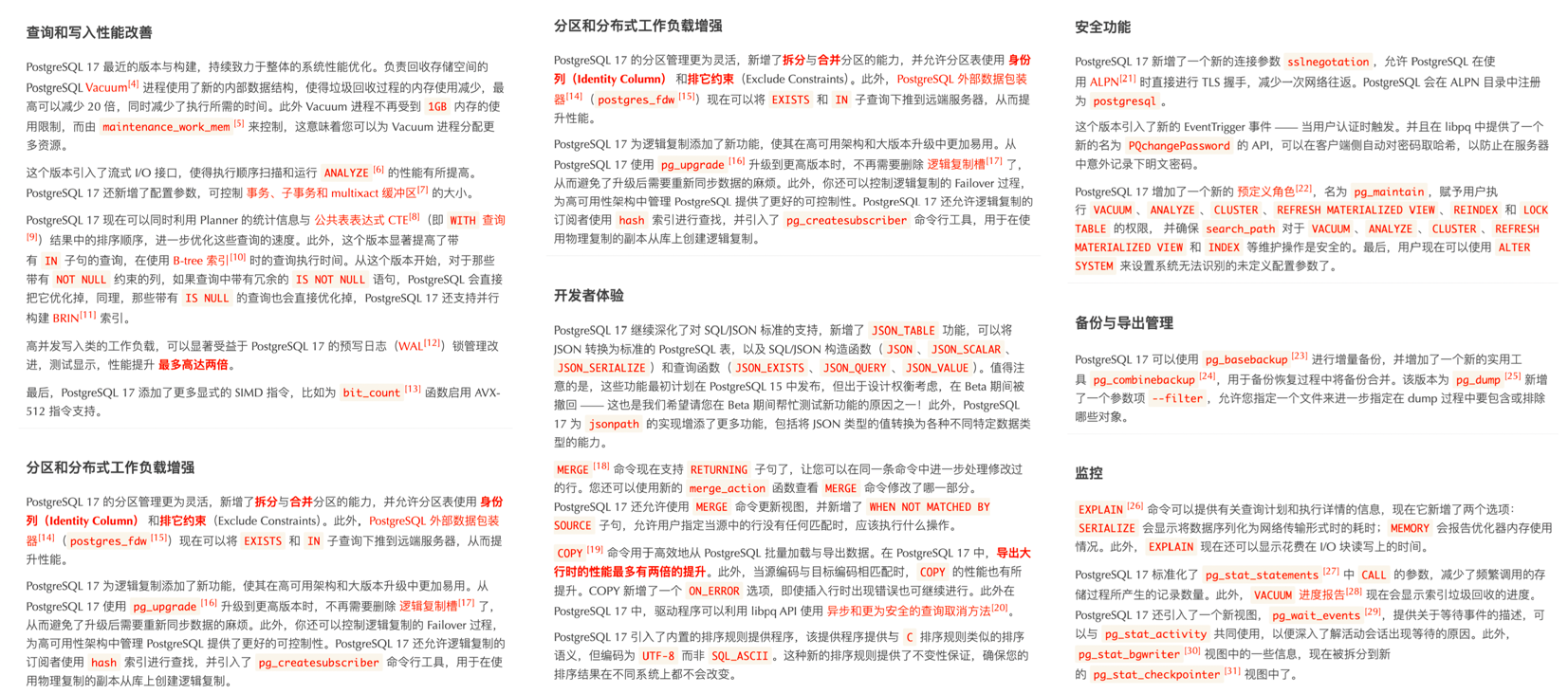

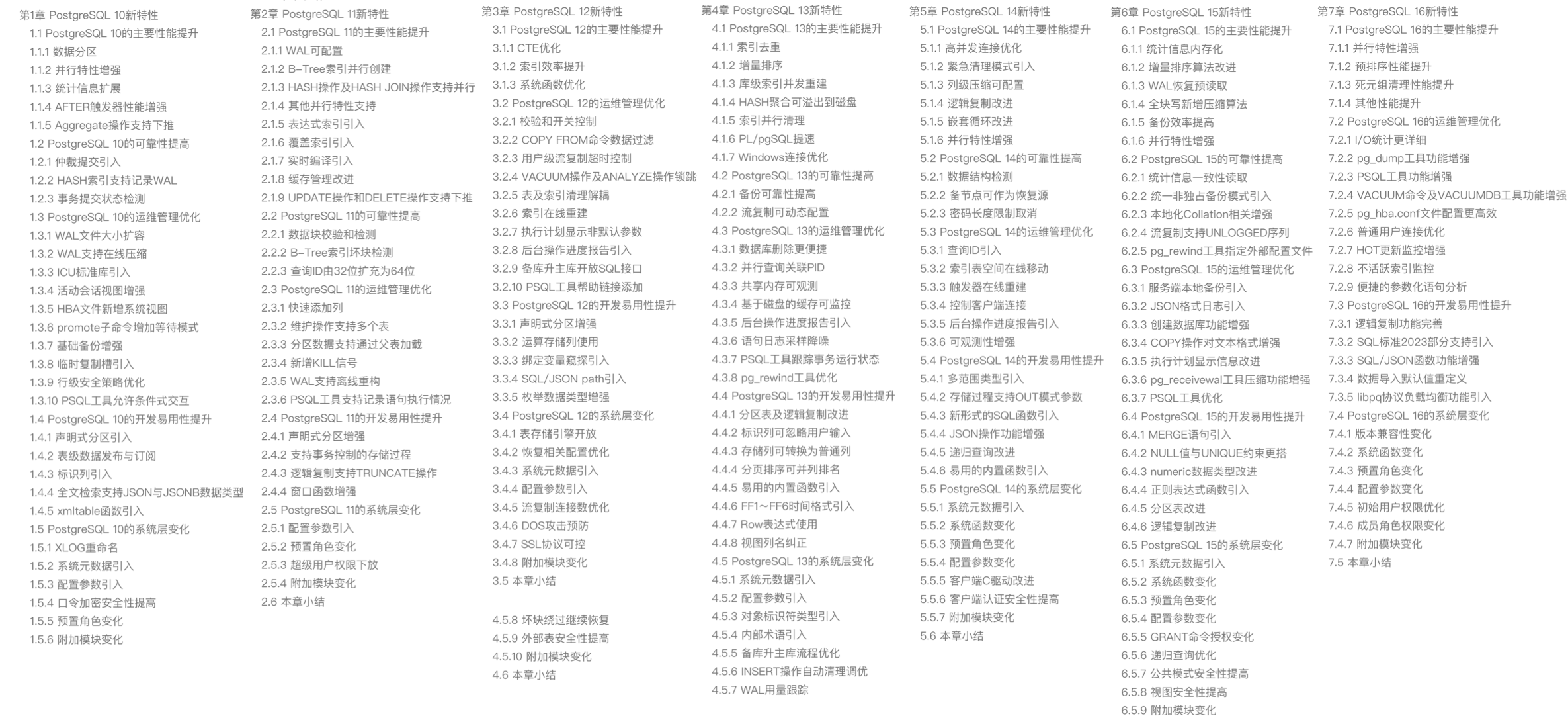

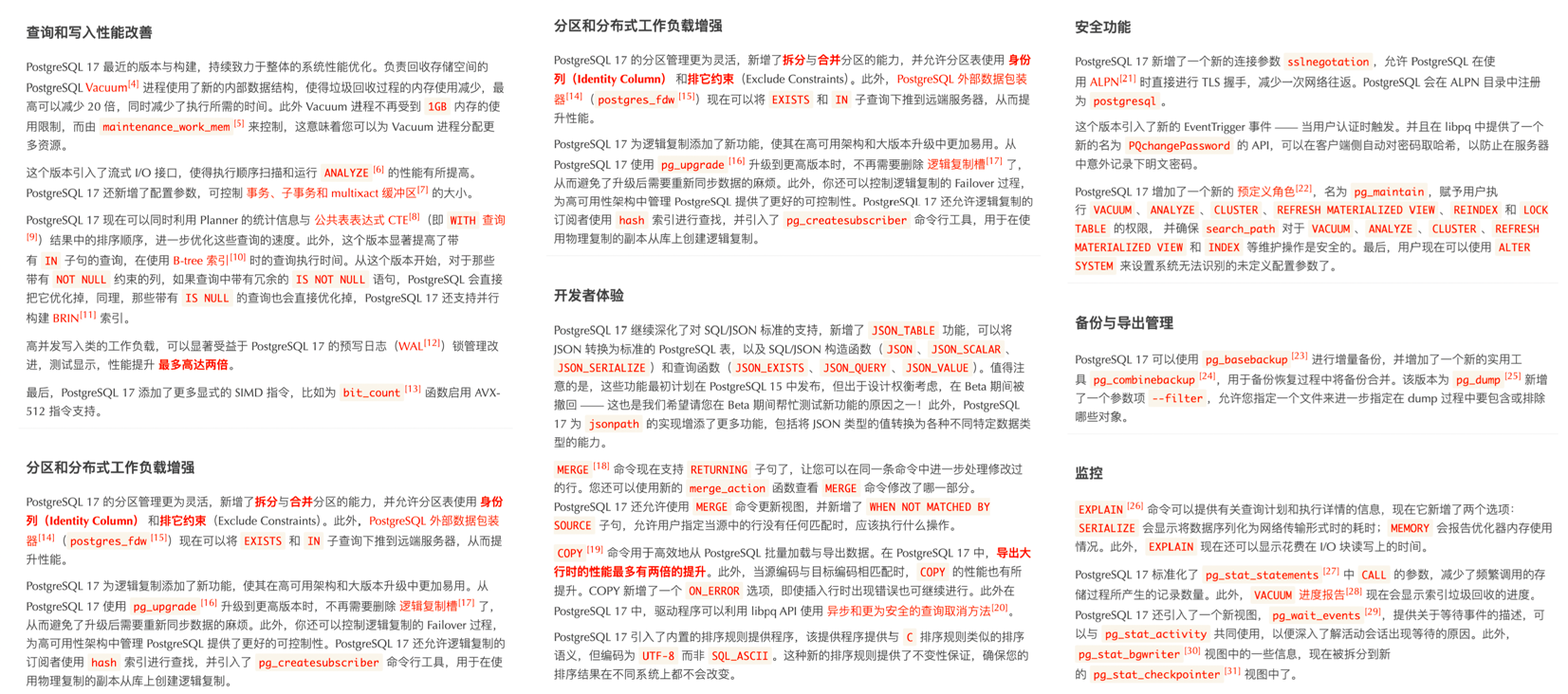

这确实是让人惊诧不已,因为 PostgreSQL 每年的大版本发布都有无数的新功能特性,例如计划今秋发布的 PostgreSQL 17 还只是 beta1,就已然有着蔚为壮观的新增特性列表:

而最近几年的 PostgreSQL 新增特性甚至足够专门编成一本书了。比如《快速掌握PostgreSQL版本新特性》便收录了 PostgreSQL 最近七年的重要新特性 —— 将目录塞的满满当当:

回头再来看看 MySQL 9 更新的六个特性,后四个都属于无关痛痒,一笔带过的小修补,拿出来讲都嫌丢人。而前两个 向量数据类型 和 JS存储过程 才算是重磅亮点。

BUT ——

MySQL 9.0 的向量数据类型只是 BLOB 类型换皮 —— 只加了个数组长度函数,这种程度的功能,28年前 PostgreSQL 诞生的时候就支持了。

而 MySQL Javascript 存储过程支持,竟然还是一个 企业版独占特性,开源版不提供 —— 而同样的功能,13年前 的 PostgreSQL 9.1 就已经有了。

时隔八年的 “创新大版本” 更新就带来了俩 “老特性”,其中一个还是企业版特供。“创新”这俩字,在这里显得如此辣眼与讽刺。

枯萎收缩的生态规模

对一项技术而言,用户的规模直接决定了生态的繁荣程度。瘦死的骆驼比马大,烂船也有三斤钉。 MySQL 曾经搭乘互联网东风扶摇而起,攒下了丰厚的家底,它的 Slogan 就很能说明问题 —— “世界上最流行的开源关系型数据库”。

不幸地是在 2023 年,至少根据全世界最权威的开发者调研之一的 StackOverflow Annual Developer Survey 结果来看,MySQL 的使用率已经被 PostgreSQL 反超了 —— 最流行数据库的桂冠已经被 PostgreSQL 摘取。

特别是,如果将过去七年的调研数据放在一起,就可以得到这幅 PostgreSQL / MySQL 在专业开发者中使用率的变化趋势图(左上) —— 在横向可比的同一标准下,PostgreSQL 流行与 MySQL 过气的趋势显得一目了然。

对于中国来说,此消彼长的变化趋势也同样成立。但如果对中国开发者说 PostgreSQL 比 MySQL 更流行,那确实是违反直觉与事实的。

将 StackOverflow 专业开发者按照国家细分,不难看出在主要国家中(样本数 > 600 的 31 个国家),中国的 MySQL 使用率是最高的 —— 58.2% ,而 PG 的使用率则是最低的 —— 仅为 27.6%,MySQL 用户几乎是 PG 用户的一倍。

与之恰好反过来的另一个极端是真正遭受国际制裁的俄联邦:由开源社区运营,不受单一主体公司控制的 PostgreSQL 成为了俄罗斯的数据库大救星 —— 其 PG 使用率以 60.5% 高居榜首,是其 MySQL 使用率 27% 的两倍。

中国因为同样的自主可控信创逻辑,最近几年 PostgreSQL 的使用率也出现了显著跃升 —— PG 的使用率翻了三倍,而 PG 与 MySQL 用户比例已经从六七年前的 5:1 ,到三年前的3:1,再迅速发展到现在的 2:1,相信会在未来几年内会很快追平并反超世界平均水平。 毕竟,有这么多的国产数据库,都是基于 PostgreSQL 打造而成 —— 如果你做政企信创生意,那么大概率已经在用 PostgreSQL 了。

抛开政治因素,用户选择使用一款数据库与否,核心考量还是质量、安全、效率、成本等各个方面是否“先进”。先进的因会反映为流行的果,流行的东西因为落后而过气,而先进的东西会因为先进变得流行,没有“先进”打底,再“流行”也难以长久。

究竟是谁杀死了MySQL?

究竟是谁杀死了 MySQL,难道是 PostgreSQL 吗?Peter Zaitsev 在《Oracle最终还是杀死了MySQL》一文中控诉 —— Oracle 的不作为与瞎指挥最终害死了 MySQL;并在后续《Oracle还能挽救MySQL吗》一文中指出了真正的根因:

MySQL 的知识产权被 Oracle 所拥有,它不是像 PostgreSQL 那种 “由社区拥有和管理” 的数据库,也没有 PostgreSQL 那样广泛的独立公司贡献者。不论是 MySQL 还是其分叉 MariaDB,它们都不是真正意义上像 Linux,PostgreSQL,Kubernetes 这样由社区驱动的的原教旨纯血开源项目,而是由单一商业公司主导。

比起向一个商业竞争对手贡献代码,白嫖竞争对手的代码也许是更为明智的选择 —— AWS 和其他云厂商利用 MySQL 内核参与数据库领域的竞争,却不回馈任何贡献。于是作为竞争对手的 Oracle 也不愿意再去管理好 MySQL,而干脆自己也参与进来搞云 —— 仅仅只关注它自己的 MySQL heatwave 云版本,就像 AWS 仅仅专注于其 RDS 管控和 Aurora 服务一样。在 MySQL 社区凋零的问题上,云厂商也难辞其咎。

逝者不可追,来者犹可待。PostgreSQL 应该从 MySQL 的衰亡中吸取教训 —— 尽管 PostgreSQL 社区非常小心地避免出现一家独大的情况出现,但生态确实在朝着一家/几家巨头云厂商独大的不利方向在发展。云正在吞噬开源 —— 云厂商编写了开源软件的管控软件,组建了专家池,通过提供维护攫取了软件生命周期中的绝大部分价值,但却通过搭便车的行为将最大的成本 —— 产研交由整个开源社区承担。而 真正有价值的管控/监控代码却从来不回馈开源社区 —— 在数据库领域,我们已经在 MongoDB,ElasticSearch,Redis,以及 MySQL 上看到了这一现象,而 PostgreSQL 社区确实应当引以为鉴。

好在 PG 生态总是不缺足够头铁的人和公司,愿意站出来维护生态的平衡,反抗公有云厂商的霸权。例如,我自己开发的 PostgreSQL 发行版 Pigsty,旨在提供一个开箱即用、本地优先的开源云数据库 RDS 替代,将社区自建 PostgreSQL 数据库服务的底线,拔高到云厂商 RDS PG 的水平线。而我的《云计算泥石流》系列专栏则旨在扒开云服务背后的信息不对称,从而帮助公有云厂商更加体面,亦称得上是成效斐然。

尽管我是 PostgreSQL 的坚定支持者,但我也赞同 Peter Zaitsev 的观点:“如果 MySQL 彻底死掉了,开源关系型数据库实际上就被 PostgreSQL 一家垄断了,而垄断并不是一件好事,因为它会导致发展停滞与创新减缓。PostgreSQL 要想进入全盛状态,有一个 MySQL 作为竞争对手并不是坏事”

至少,MySQL 可以作为一个鞭策激励,让 PostgreSQL 社区保持凝聚力与危机感,不断提高自身的技术水平,并继续保持开放、透明、公正的社区治理模式,从而持续推动数据库技术的发展。

MySQL 曾经也辉煌过,也曾经是“开源软件”的一杆标杆,但再精彩的演出也会落幕。MySQL 正在死去 —— 更新疲软,功能落后,性能劣化,质量出血,生态萎缩,此乃天命,实非人力所能改变。 而 PostgreSQL ,将带着开源软件的初心与愿景继续坚定前进 —— 它将继续走 MySQL 未走完的长路,写 MySQL 未写完的诗篇。

数据库火星撞地球:当PG爱上DuckDB

蹭热点引出的好话题

昨晚在直播间,我与几位国内 DuckDB 先锋进行了一场对谈。 话题跨度很大,从 DeepSeek 团队在开源周推出的分布式 DuckDB 分析框架 “Smallpond”,聊到 PostgreSQL 与 DuckDB 的深度融合,相当热闹。

DeepSeek 的开源的 “小池塘”用把 DuckDB 改为分布式的用法,从营销上给 DuckDB 打了很好的广告。 但从实用角度和影响力来说,我个人对分布式 DuckDB 的价值保持保留态度(那个3FS实际上更有用)。 因为这与 DuckDB 本身的核心价值主张(大数据已死)完全背道而驰。

那么如果不去折腾 “分布式”,DuckDB 未来更有前景的方向是什么? 相比之下,我更加看好 “ DuckDB + PostgreSQL深度融合” 这路径。 我甚至认为,它可能会引爆数据库世界下一场“火星撞地球”式的变革。

DuckDB:OLAP挑战者

DuckDB 由 Mark Raasveldt 和 Hannes Mühleisen 在荷兰的 CWI (国家数学与计算机科学研究所)开发 —— 而 CWI 不仅仅是一个研究机构,可以说是分析型数据库领域发展背后的幕后推手与功臣,是列式存储引擎与向量化查询执行的先驱。

现在你能看到的各种分析数据库产品 ClickHouse,Snowflake,Databricks 背后都有它的影子。 而现在这些分析领域的先锋们自己亲自下场来做分析数据库,他们选择了一个非常好的时机与生态位切入,搞出了一个嵌入式的 OLAP 分析数据库 —— DuckDB 。

DuckDB 的起源来自作者们对数据库用户痛点的观察:数据科学家主要使用像 Python 与 Pandas 这样的工具,不怎么熟悉经典的数据库。 经常被如何连接,身份认证,数据导入导出这些工作搞的一头雾水。那么有没有办法做一个简单易用的嵌入式分析数据库给他们用呢?—— 就像 SQLite 一样。

DuckDB 整个数据库软件源代码就是一个头文件一个c++文件,编译出来就是一个独立二进制,数据库本身也就一个简单的文件。 使用兼容 PostgreSQL 的解析器与语法,简单到几乎没有任何上手门槛。尽管 DuckDB 看上去非常简单,但它最了不起的一点在于 —— 简约而不简单,分析性能也是绝冠群雄。例如,在 ClickHouse 自己的主场 ClickBench 上,有着能够吊打东道主 ClickHouse 的表现。

同时,DuckDB 使用极为友善的 MIT 许可证开源:一个有着顶尖性能表现,而使用门槛低到地板,还开源免费,允许随意包装套壳的数据库,想不火都难。

取长补短的黄金组合

尽管 DuckDB 有着顶级的分析性能,但它也有自己的短处 —— 薄弱的数据管理能力, 也就是数据科学家们不喜欢的那些东西 —— 认证/权限,访问控制,高并发,备份恢复,高可用,导入导出,等等等, 而这恰好是经典数据库的长处,也是企业级分析系统的核心痛点。

从这个角度来说,duckdb 更像是 RocksDB 这样的底层 “存储引擎”,一个 OLAP 算子。 本身距离一个真正的 “数据库” / “大数据分析平台” 还有很多工作要做。

PostgreSQL 则在数据管理领域深耕多年,拥有完善的事务机制、权限控制、备份恢复和扩展机制。 传统的 OLTP 场景下 PostgreSQL 更是 “老牌猛将” 。 但 PostgreSQL 的一个主要遗憾就是:尽管PostgreSQL 本身提供了很强大的分析功能集,应付常规的分析任务绰绰有余。 但在较大数据量下全量分析的性能,相比专用的实时数仓仍然有些不够看。

那么人们自然而然会想到,如果我们可以结合两者的能力,PostgreSQL 提供全面的管理功能与生态支持,以及顶级的 OLTP 性能。 DuckDB 提供顶尖的分析算子和 OLAP 性能;二者深度融合,就能把各自优势叠加,取长补短,在数据库领域中产生一个“新物种”。

DuckDB 能很好的解决 PostgreSQL 的分析短板,甚至还可以通过读写远程对象存储上的 Parquet 等列存文件格式,实现无限存储的数据湖仓的效果;而 DuckDB 孱弱的管理能力也通过融合成熟的 PostgreSQL 生态得到完美解决。 比起给 DuckDB 套壳,搞一套什么新的 “大数据平台/数据管理系统”,或者给 PostgreSQL 发明一个新的分析引擎,两者融合起来,取长补短,是一条阻力最小,而价值最大的道路。

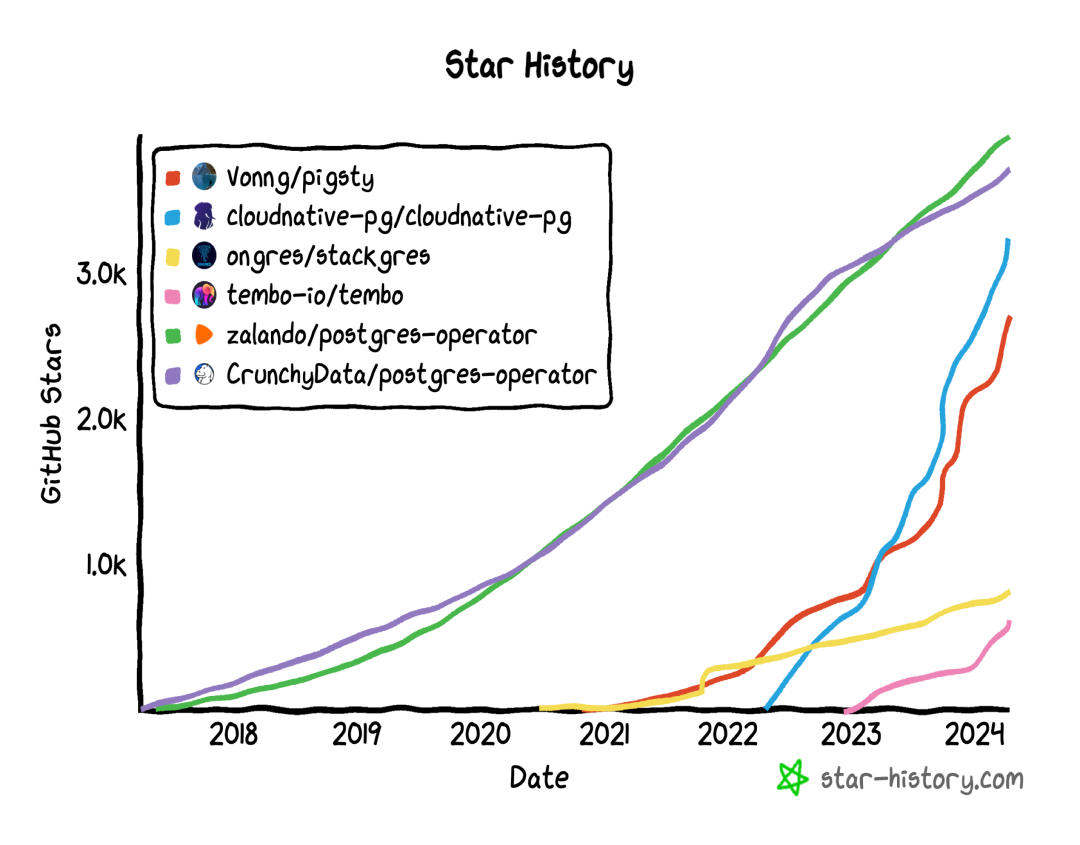

实际上,这正是数据库世界中正在发生的事情,许多团队和厂商已经投入到 DuckDB + PostgreSQL 的缝合当中,试图率先抢得这个潜力巨大的新市场。

群雄逐鹿的缝合赛道

当我们把目光投向业界,不难发现 已经有诸多玩家入局了:

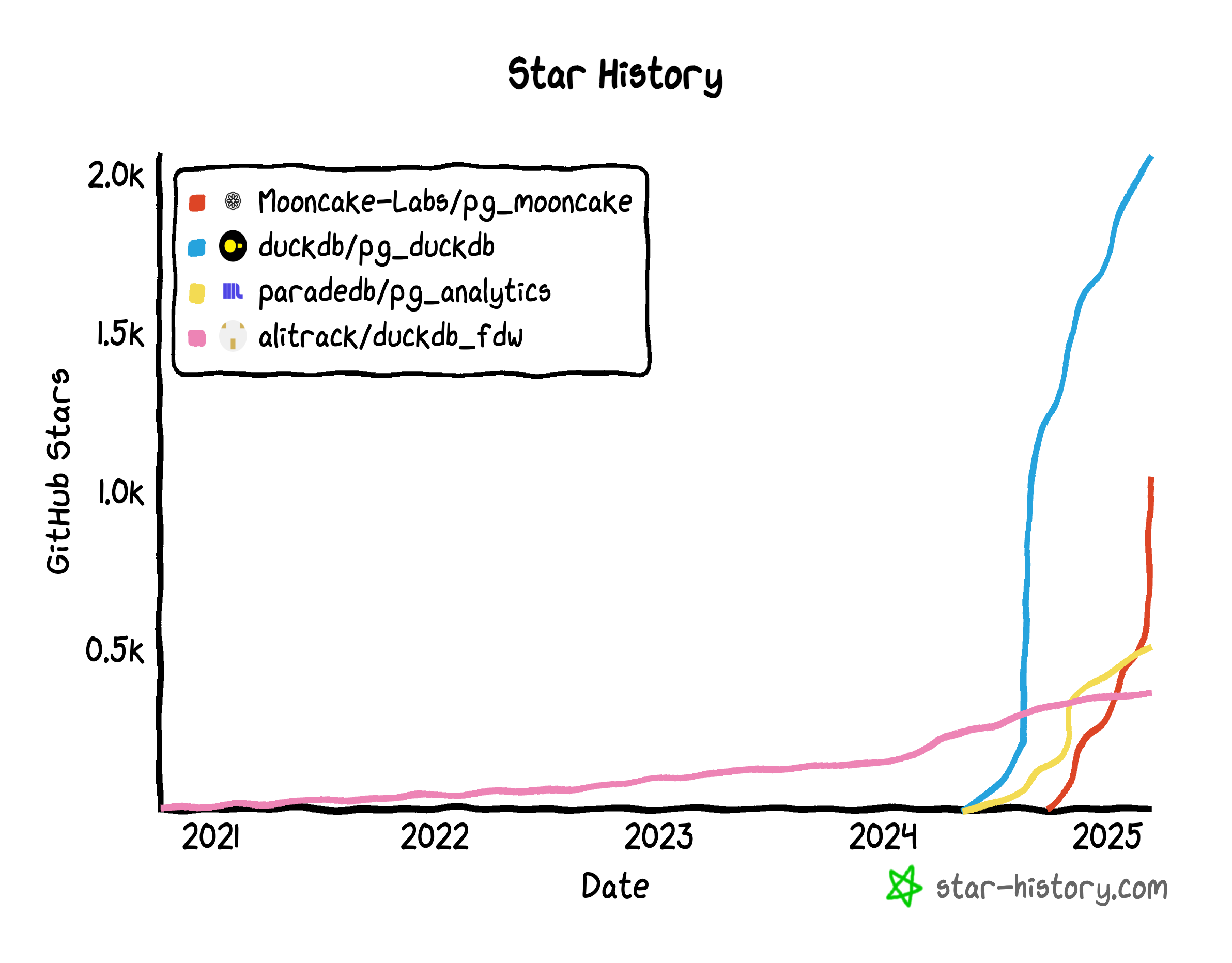

最早进入这条赛道的是国内个人开发者李红艳开发的 duckdb_fdw,一直算是不温不火的状态。

然而在 《PostgreSQL正在吞噬数据库世界》以向量数据库的例子预言了 OLAP 赛道的机会之后,

PG 社区对征服 OLAP 缝合 DuckDB 的热情被彻底点燃。

就在 2024 年 3 月的时间点上,一切骤然加速。ParadeDB 的 pg_analytics 插件立即切换了技术路线,改为缝合 DuckDB。

PG 生态发起 pg_quack 项目的 HYDRA 与 DuckDB 母公司 MotherDuck 开始合作,发起了 pg_duckdb。

官方开始下场, “不误正业” 地不去折腾 DuckDB,反而搞起了 PostgreSQL 插件。

接下来,在数据库热点上一向嗅觉敏锐的 Neon 赞助了 pg_mooncake 项目,这个新玩家选择站在 pg_duckdb 的肩膀上,

不仅要把 DuckDB 的计算能力给缝合入 PG,还要将 DuckDB / Parquet 开放分析存储格式原生融合到 PG 的表访问接口中,把存储和计算能力一起缝合到 PG 中。

一些头部云厂商,比如 阿里云rds 也在尝试缝合包装 DuckDB,标志着已经有大玩家开始忍不住准备下场了。

这种场面很容易让人联想到早两年的“向量数据库热”。当 AI 检索和语义搜索成为热点,不少厂商都“闻风而动”,基于 PostgreSQL 开发向量数据库插件,

AI爆火之后,PG 生态里就涌现出了至少六款向量数据库扩展( pgvector,pgvector.rs,pg_embedding,latern,pase,pgvectorscale),

并在你追我赶的赛马中卷出了新高度。

最后 pgvector 在以 AWS 为代表的厂商大力投入加注之下,在其他数据库比如 Oracle / MySQL / MariaDB 的糊弄版本姗姗来迟之前,

就已经把整个专用向量数据库细分领域给荡平了,吃下了 RAG / 向量数据库带来巨大增量里的最大蛋糕。而现在,似乎是这种赛事在 OLAP 领域的又一次预演。

为什么是DuckDB+PG?

比较有趣的一点是,这样的奇景同样只出现在 PostgreSQL 生态中,而在其他数据库社区中依然一片寂静。 甚至 DuckDB 官方也在参加 PostgreSQL 缝合大赛,而不是其他什么 DB 的缝合大赛。

所以有人会问:既然要跟 DuckDB 融合,为什么不选 MySQL、Oracle、SQL Server 甚至 MongoDB? 难道这些数据库就没有管理能力,不需要取长补短,不能跟 DuckDB 融合,获取顶级 OLAP 能力吗?

PostgreSQL 与 DuckDB 是一对完美的组合,体现在三点上:功能互补,语法兼容,可扩展性:

首先,DuckDB 使用的是 PostgreSQL 语法,甚至语法解析器都是直接照搬 PG 的, 这意味着两者关键接口的差异性非常小,天然具有亲和力,也就是不怎么需要折腾。

第二,PostgreSQL 和 DuckDB 这两个数据库均是公认的“可扩展性怪物”。无论是 FDW、插件,还是新存储引擎、新类型,都能以扩展的形式接入。 比起魔改 PG + DuckDB 的内核源码,写一个粘合两边现有接口的扩展插件显然要简单太多了,

这种天生的技术血缘亲和力,让 “PG + DuckDB” 的融合成本显著低于所有其他组合,低到李老师这样的独立个人开发者都可以参赛(顺势而为是好事,无任何贬义)。

与此同时 PostgreSQL 是世界上最流行的数据库,也是主要数据库中唯一有增长而且是高速增长的玩家,缝合 PostgreSQL 带来的收益也要比其他数据库大得多。

这意味着,“PG + DuckDB” 的融合,是一条“阻力最小、价值最大”的康庄大道,大自然厌恶真空,因此自然会有许多玩家下场来填补这里的空白生态位。

统一 OLTP 与 OLAP 的梦想

在数据库领域,OLTP 与 OLAP 的分裂由来已久。所有的“数据仓库 + 关系型数据库”架构、ETL 和 CDC 流程,都是在修修补补这道裂痕。 如果 PostgreSQL 在保留其 OLTP 优势的同时,能嫁接上 DuckDB 的 OLAP 性能,企业还有必要再维护一套专门的分析数据库吗?

这不仅意味着**“降本增效”**,更可能带来工程层面的简化:无需再为数据迁移和多数据库同步烦恼,也无需支付昂贵的双套维护成本。 一旦有人把这件事做得足够好,就会像“一颗深水炸弹”般冲击现在大数据分析的市场格局。

PostgreSQL 被视为“数据库界的 Linux 内核” —— 它的开源精神和极强的可扩展性允许无限可能。 而我们目睹着 PostgreSQL 使用这种方式,依次占领了地理信息,时序数据,NoSQL文档,向量嵌入等领域。 而现在,它正准备向最后也是最大的生态位 —— OLAP 分析领域发起冲击。

只要一个优秀的集成方案出现,能让 DuckDB 提供的高性能分析与 PostgreSQL 的生态完美融合,整个大数据分析领域或许会因此大变天。 那些专门的 OLAP 产品,能否顶住这场“核爆级”冲击?是否会像那些 “专用向量数据库” 一样凋零, 现在没人愿意给出答案,但我相信到时候大家都会有自己的判断。

为PG与DuckDB缝合铺好路

PostgreSQL OLAP 生态的现状,正如同两年前的向量数据库插件一样,还处于早期阶段。 但这已经足够令人兴奋:新技术的魅力就在于,你能预见它的潜力,就能率先拥抱它的爆发。

两年前 PGVECTOR 爆火前夜,Pigsty 是第一波将其整合的 PostgreSQL 发行版,也是我将它提入 PGDG 官方扩展仓库的。 而这场 DuckDB 缝合大赛,干脆就是我点的火。能点燃这样的赛事,我自然也会在这场新的赛事中,提前为 PG 与 DuckDB 的融合铺好路。

作为一名深耕数据库领域的从业者,我正在把当前各家与 DuckDB 融合的 PostgreSQL 插件 全部打包成可直接安装使用的 RPM 或 DEB 包,并在主流的十个 Linux 发行版上提供, 与 PGDG 官方内核完全兼容,开箱即用,让普通用户也能轻松体验“DuckDB + PG”融合的威力。 最重要的是,提供一个缝合大赛的“竞技舞台”,让所有玩家都平等参与进来。

诚然,现在不少插件仍处于早期阶段,稳定性和功能尚未达到“企业级”的标准。也有很多细节待完善,比如并发访问控制、数据类型兼容、算子优化等。 机会总是属于勇于拥抱新技术的人,而我相信,这场“PG + DuckDB”融合的大戏,将会是数据库领域的下一个风口。

真正的爆炸即将开始

比起当下 AI 大模型落地在企业应用中仍显“虚浮”的热潮,OLAP 大数据分析 是一块更为庞大、也更现实的市场蛋糕。 而 PostgreSQL 与 DuckDB 的融合 则有望成为冲击这个市场的板块运动,引发行业格局的深度变革,甚至彻底打破“大数据系统 + 关系型数据库”两套架构并行的局面。

或许再过几个月到一两年的时间,我们就能看到一个或多个“融合怪物”从这些实验性项目中脱颖而出,成为数据库的新主角。 谁能先解决好扩展的易用性、集成度和性能优化,谁就能在这场新竞争中夺得先机。

对于数据库行业而言,这将是一次“火星撞地球”般的深度震荡;对于广大企业用户而言,或许会迎来一场“降本增效”的巨大机遇。 让我们拭目以待这场新趋势如何加速成长,并为数据分析与管理带来新的可能。

对比Oracle与PostgreSQL事务系统

事务系统是关系型数据库的核心组成部分,在应用开发中,为确保 数据完整性 提供了重要支持。 SQL 标准规范了数据库事务的一些功能,但并未明确规定许多细节。因此,关系型数据库的事务系统可能存在显著差异。

近年来,许多人尝试从 Oracle 数据库迁移到 PostgreSQL。为了顺利将应用从 Oracle 迁移到 PostgreSQL,理解两者事务系统之间的差异至关重要。 否则,您可能会遇到一些令人头痛的意外情况,危及到性能和数据完整性。所以,我认为有必要编写一篇文章,对比 Oracle 和 PostgreSQL 事务系统的特性。

ACID:数据库事务提供的服务

这里的 ACID 不是什么化学或药品术语,而是以下四个词的首字母缩写:

- Atomicity(原子性):保证在单个数据库事务中,所有语句作为一个整体执行,要么全部成功,要么全部不生效。这应涵盖所有类型的问题,包括硬件故障。

- Consistency(一致性):保证任何数据库事务都不会违反数据库中定义的约束。

- Isolation(隔离性):保证并发运行的事务不会导致某些“异常”(即数据库中一些不可由串行执行的事务产生的可见状态)。

- Durability(持久性):保证一旦数据库事务提交(完成),即使发生系统崩溃或硬件故障,事务也无法被撤销。

接下来,我们将详细讨论这些类别。

Oracle 与 PostgreSQL 事务的相似之处

首先,描述一下 Oracle 和 PostgreSQL 在事务管理中相同的部分是有帮助的。幸运的是,许多重要的特性都属于这一类:

- 两个数据库系统都使用多版本并发控制(MVCC):读取和写入操作互不阻塞。读取操作会读取旧数据,而在更新或删除事务进行时,不会阻塞读取。

- 两个数据库系统都在事务结束前保持锁定。

- 两个数据库系统都将 行锁 保存在行本身,而不是在锁表中。因此,锁定一行可能会导致额外的磁盘写入,但不需要进行 锁升级。

- 两个数据库系统都支持

SELECT ... FOR UPDATE进行显式的并发控制。更多关于差异的讨论,后面会说。 - 两个数据库系统都使用

READ COMMITTED作为默认的事务隔离级别,这在两个系统中的行为非常相似。

原子性对比

在这两个数据库中,原子性有一些微妙的差异:

自动提交

在 Oracle 中,任何 DML 语句会隐式启动一个数据库事务,除非已经有一个事务处于开启状态。您必须显式地使用 COMMIT 或 ROLLBACK 来结束这些事务。没有特定的语句来启动一个事务。

而 PostgreSQL 则处于 自动提交模式:除非您显式启动一个多语句事务(通过 START TRANSACTION 或 BEGIN),每个语句都会在自己的事务中运行。在此类单语句事务结束时,PostgreSQL 会自动执行 COMMIT。

许多数据库 API 允许您关闭自动提交。由于 PostgreSQL 服务器不支持禁用自动提交,客户端通过适当的时候自动发送 BEGIN 来模拟这一点。使用这样的 API,您无需担心这种差异。

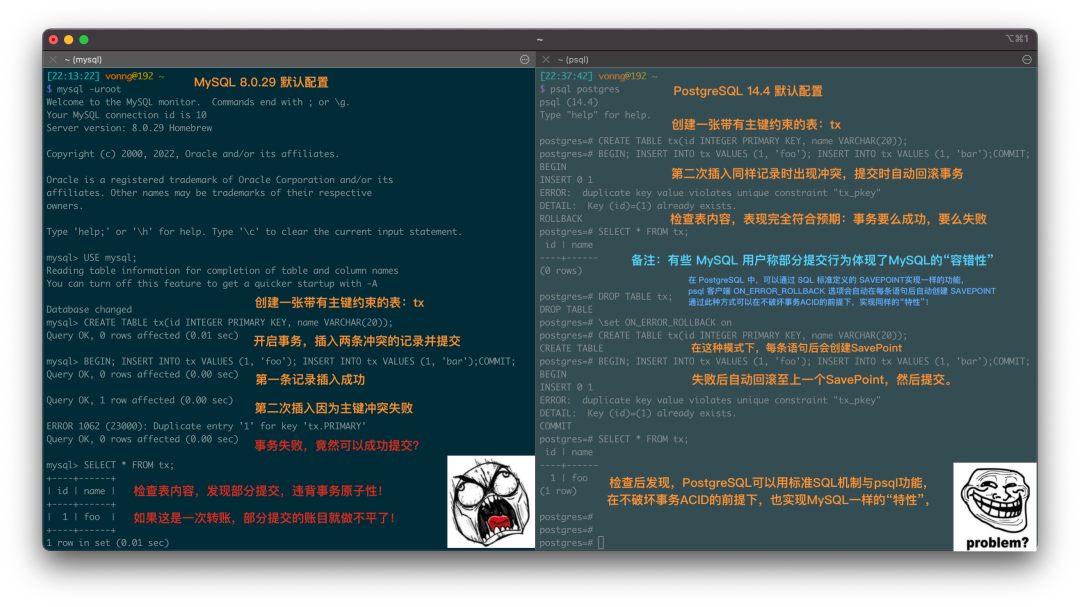

语句级回滚

在 Oracle 中,导致错误的 SQL 语句不会中止事务。相反,Oracle 会回滚失败语句的效果,事务仍然可以继续。要回滚整个事务,您需要处理错误并主动调用 ROLLBACK。

而在 PostgreSQL 中,如果事务中的 SQL 语句发生错误,整个事务会被中止。直到您使用 ROLLBACK 或 COMMIT(两者都会回滚事务)结束事务时,所有后续的语句都会被忽略。

大多数编写良好的应用程序不会遇到这个差异的问题,因为通常情况下,当发生错误时,您会希望回滚整个事务。 然而,PostgreSQL 的这种行为在某些特定情况下可能会令人烦恼:想象一个长时间运行的批处理任务,其中坏数据可能会导致错误。 您可能希望能够处理错误,而不是回滚已经完成的所有操作。在这种情况下,您应该在 PostgreSQL 中使用(符合 SQL 标准的)保存点。 请注意,您应谨慎使用保存点:它们是通过 子事务实现的,可能会严重影响性能。

事务性DDL

在 Oracle 数据库中,任何 DDL 语句会自动执行 COMMIT,因此 无法回滚 DDL 语句。

在 PostgreSQL 中则没有这种限制。除了少数例外(如 VACUUM、CREATE DATABASE、CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY等),您可以 回滚任何 SQL 语句。

一致性对比

在这一领域,Oracle 和 PostgreSQL 之间差异不大;两者都会确保事务不违反约束。

或许值得一提的是,Oracle 允许您使用 ALTER TABLE 启用或禁用约束。例如,您可以禁用约束,执行违反约束的数据修改操作,然后使用 ENABLE NOVALIDATE 启用约束(对于主键和唯一约束,只有在它们是 DEFERRABLE 时才有效)。

而在 PostgreSQL 中,只有超级用户才能禁用实现外键约束以及可推迟唯一和主键约束的触发器。设置 session_replication_role = replica 也是一个禁用此类触发器的方式,但同样需要超级用户权限。

主键和唯一约束在 Oracle 和 PostgreSQL 中的验证时机

以下 SQL 脚本在 Oracle 中不会报错:

CREATE TABLE tab (id NUMBER PRIMARY KEY);

INSERT INTO tab (id) VALUES (1);

INSERT INTO tab (id) VALUES (2);

COMMIT;

UPDATE tab SET id = id + 1;

COMMIT;

在 PostgreSQL 中,同样的脚本会报错:

CREATE TABLE tab (id numeric PRIMARY KEY);

INSERT INTO tab (id) VALUES (1);

INSERT INTO tab (id) VALUES (2);

UPDATE tab SET id = id + 1;

ERROR: duplicate key value violates unique constraint "tab_pkey"

DETAIL: Key (id)=(2) already exists.

原因在于,PostgreSQL 默认在每行变化时检查约束(不同于SQL标准),而 Oracle 在语句结束时检查约束。

不过这个问题可以通过将约束创建为 DEFERRABLE 来解决,这样 PostgreSQL 会在语句结束时检查约束,并与 Oracle 的行为保持一致。

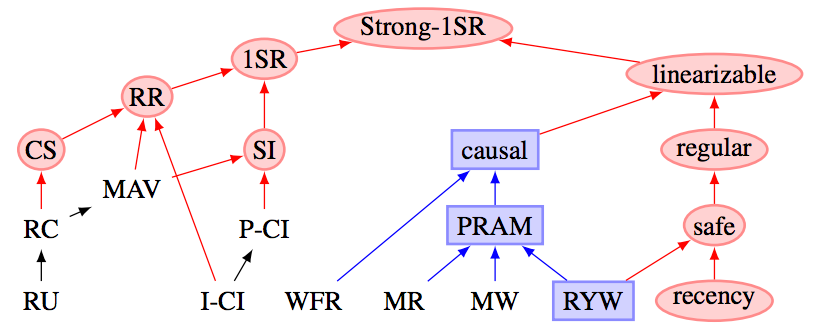

隔离性对比

这是 Oracle 和 PostgreSQL 差异最明显的领域。Oracle 对事务隔离的支持相对有限。

事务隔离级别的对比

SQL 标准定义了四个事务隔离级别:READ UNCOMMITTED、READ COMMITTED、REPEATABLE READ 和 SERIALIZABLE。

但与标准的详细程度相比,单独的级别定义得比较模糊。例如,标准提到,“脏读”(读取其他事务未提交的数据)在 READ UNCOMMITTED 隔离级别下是“可能”的,但并没有明确指出这是否为必需。

Oracle 只提供 READ COMMITTED 和 SERIALIZABLE 隔离级别。然而后者其实并不完全准确;Oracle 提供的是快照隔离。例如,以下并发事务均会成功(第二个会话如下所示):

CREATE TABLE tab (name VARCHAR2(50), is_highlander NUMBER(1) NOT NULL);

-- start a new serializable transaction

SET TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL SERIALIZABLE;

SELECT count(*) FROM tab WHERE is_highlander = 1;

COUNT(*)

----------

0

-- start a new serializable transaction

SET TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL SERIALIZABLE;

SELECT count(*) FROM tab WHERE is_highlander = 1;

COUNT(*)

----------

0

-- the count is zero, so let's proceed

INSERT INTO tab VALUES ('MacLeod', 1);

COMMIT;

-- the count is zero, so let's proceed

INSERT INTO tab VALUES ('Kurgan', 1);

COMMIT;

如果这些事务串行执行,第二个事务的结果应该是 count 为 1。

除了不准确,Oracle 的实现还存在许多问题。例如,如果您创建一个表时未指定 SEGMENT CREATION IMMEDIATE,然后在 SERIALIZABLE 事务中尝试插入第一行,就会遇到序列化错误。

虽然这在技术上是合法的,但如果在更高的隔离级别遇到问题时,Oracle 会经常抛出序列化错误。

PostgreSQL 支持所有四个隔离级别,但它会默默地将 READ UNCOMMITTED 升级为 READ COMMITTED(这在 SQL 标准中可能并不符合要求)。

而 SERIALIZABLE 事务则是真正的串行化事务。PostgreSQL 的 REPEATABLE READ 行为类似于 Oracle 的 SERIALIZABLE,但实际上 PostgreSQL 的实现更好。

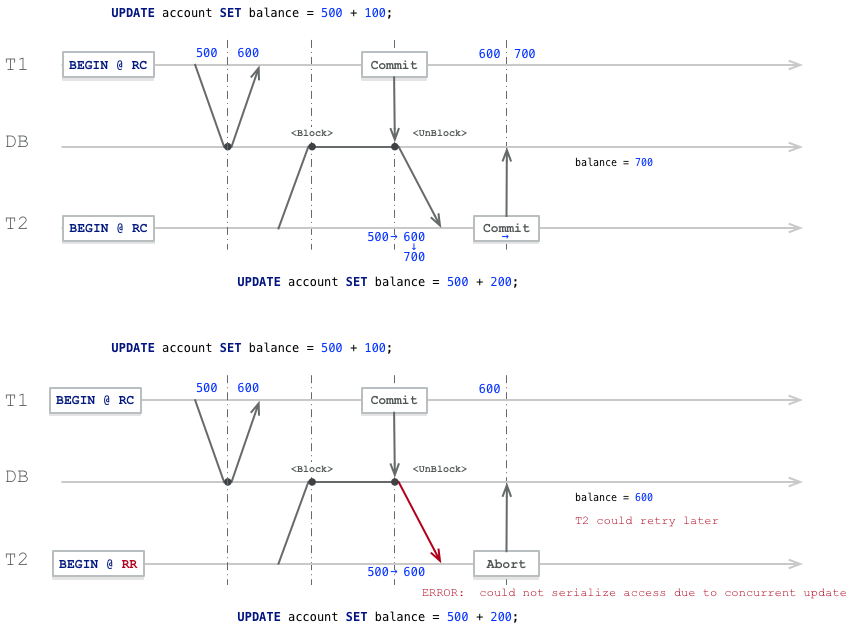

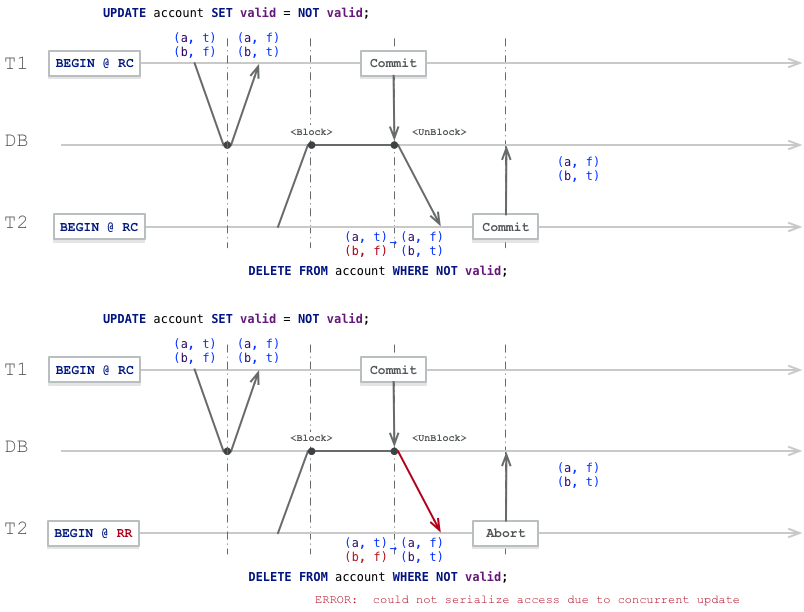

READ COMMITTED 级别下并发数据修改的对比

默认的事务隔离级别 READ COMMITTED 是一个低隔离级别,这意味着许多异常仍然可能发生。

我在之前的文章中描述了其中的一种异常:事务异常与 SELECT FOR UPDATE。简而言之,情况如下:

- 一个事务修改了表中的一行,但尚未提交

- 第二个事务执行了一个锁定行的语句(例如

SELECT ... FOR UPDATE),并且挂起 - 第一个事务提交

在这种情况下,两个数据库系统会有什么结果?在 Oracle 和 PostgreSQL 中,您都能看到最新提交的数据,但细节有所不同:

- PostgreSQL 只重新评估被锁定的行,操作较快,但可能会导致不一致的结果

- Oracle 会 重新执行完整查询,尽管速度较慢,但能够提供一致的结果

持久性对比

两个数据库系统都通过事务日志实现持久性(Oracle 中为“REDO 日志”,PostgreSQL 中为“WAL日志”)。在这一领域,Oracle 和 PostgreSQL 提供的保证是相同的。

其他事务差异

事务的大小和持续时间限制

这一领域的差异主要源于 Oracle 和 PostgreSQL 实现多版本并发控制(MVCC)的方式不同。Oracle 使用 UNDO 表空间 来存储已修改行的旧版本,而 PostgreSQL 将多个版本的行存储在表中。

由于这个原因,Oracle 事务中数据修改的数量受限于 UNDO 表空间的大小。对于大批量删除或更新,Oracle 通常会采用分批处理并在每批之间执行 COMMIT。

而在 PostgreSQL 中没有这种限制,但大规模更新会导致表膨胀,因此您也可能希望分批更新,并在更新间运行 VACUUM。然而在 PostgreSQL 中,并没有理由限制大批量删除的规模。

长时间运行的事务在任何关系型数据库中都是一个问题,因为它们会占用锁并增加阻塞其他会话的几率,长事务也更容易遭遇死锁。 在 PostgreSQL 中,长事务会比 Oracle 更加棘手一些,因为它们还会阻塞“自动清理”(autovacuum)任务的进程,从而导致表膨胀,治理起来要费些事。

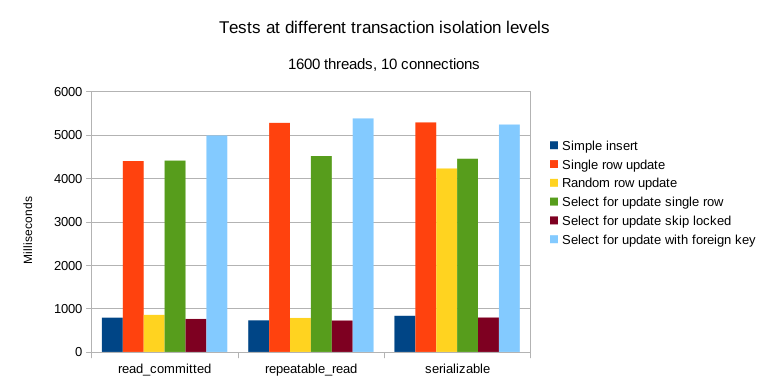

SELECT ... FOR UPDATE 的对比

两个数据库系统都知道这个命令,它用于同时读取并锁定一行。Oracle 和 PostgreSQL 都支持 NOWAIT 和 SKIP LOCKED 子句。

PostgreSQL 缺少 WAIT <integer> 子句,但是可以通过动态调整 lock_timeout 参数实现类似的功能。

这里最重要的区别在于,PostgreSQL 中如果你打算更新某一行,FOR UPDATE 并非 合适的语句 ——

除非你打算删除某行或修改主键或唯一键列,否则正确的锁定模式应为 FOR NO KEY UPDATE。

事务ID回卷

事务ID回卷 只在 PostgreSQL 中存在。 PostgreSQL 的多版本控制通过在每一行中存储 事务ID 来管理行版本的可见性。

这些编号来自一个 32 位整型计数器,最终会发生回卷。

所以 PostgreSQL 需要执行维护操作(FREEZE)来避免出现事务ID回卷。在高事务量(TPS)的系统中,这可能成为一个需要特别关注和调整的问题。

结论

在大多数方面,Oracle 和 PostgreSQL 的事务行为非常相似。但它们之间确实存在差异,如果您计划迁移到 PostgreSQL,了解这些差异是很重要的。本文中的对比有助于您在迁移过程中识别潜在的问题。

老冯评论

在 PostgreSQL 17 发布:摊牌了,我不装了! 中提到过,在最近一年,PostgreSQL 社区在心态与精神上有了显著的转变: 不再采用过去佛系与世无争的姿态,而是转变为一种积极进取的姿态,它已经做好了接管与征服整个数据库世界的心理建设与准备。喊出了干翻“顶级商业数据库”(Oracle)的口号。

现在看来,PostgreSQL 社区确实出息了,前有 EDB TPC-C 评测炮打 Oracle 性能,现在又有 Cybertec 点评 Oracle 事务正确性,开始炮轰 Oracle 了。

就比如这篇文章吧,看上去很中立的说了一堆事务系统的对比,也很客观的指出了 PG 和 Oracle 存在的问题。 但实际上在 ACID 的 ACD 上大家都是大同小异,真正的重点是在事务隔离等级上 —— Oracle 的缺陷实现。

是的,号称顶级商业数据库的 Oracle,Serializable 的隔离等级其实是虚标,实际上是 SI 快照隔离。 这个问题其实我在 MySQL的正确性为何如此拉垮? 中已经提到了。

在主流 DBMS 中,只有 PostgreSQL (以及基于PostgreSQL的CockroachDB)提供了真正的 Serializable 。

数据库即业务架构

数据库是业务架构的核心,是不言自明的共识。但如果我们更进一步,将数据库作为架构本身,又会发生什么? 未来会是一个数据库吞噬后端,前端,操作系统,甚至一切的世界吗?

数据库是架构的核心

“If you show me your software architecture, I learn nothing about your business. But if you show me your data model, I can guess exactly what your business is.”。 —— Michael Stonebraker

数据库祖师爷迈克·石破天有句名言:“如果你给我看软件架构,我对你的业务一无所知;但如果你给我看数据模型,我就能精准知道你的业务是干嘛的”

无独有偶,微软 CEO 纳德拉 也在最近公开表示:我们今天所称的软件,你喜欢的那些应用程序,不过是包装精美的数据库操作界面而已。

即使在 GenAI / LLM 爆火的当下,绝大多数信息系统依然是以数据库为核心设计。所谓的分库分表,几地几中心,异地多活这些架构花活,说到底也就是数据库的不同使用方式罢了。

数据库是业务架构的核心,早已是不言自明的共识。但如果我们更进一步,将数据库作为业务架构本身,又会如何?

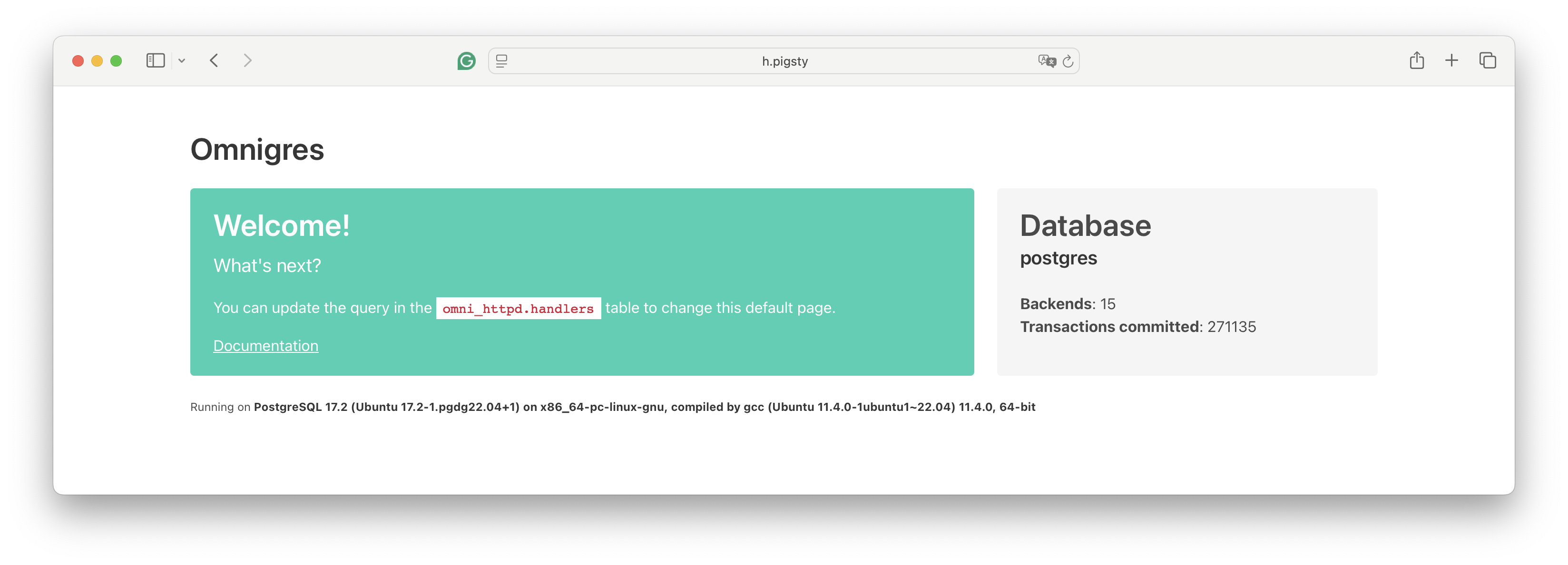

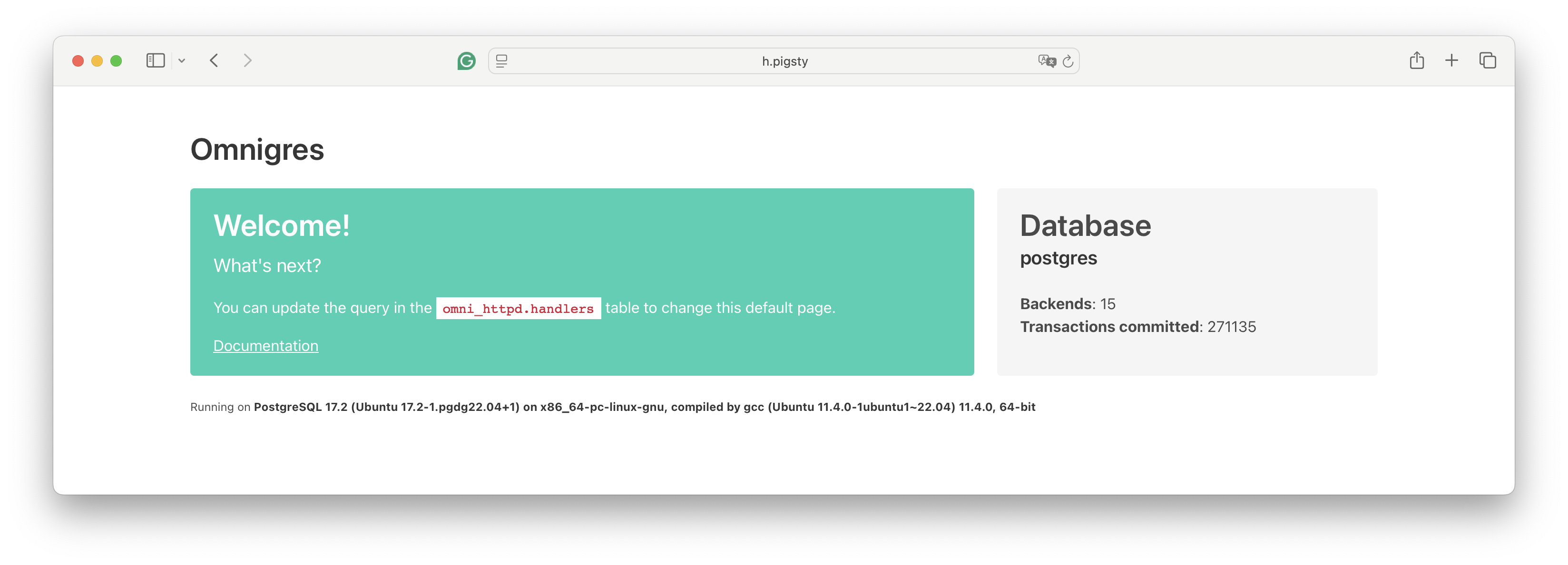

驱动未来的数据库

不久之前,我邀请 Omnigres 创始人 Yurii 到 第七届PG生态大会 上进行分享。 他在题为《数据库驱动未来》 的演讲中抛出了一个有趣的观点 —— 数据库就是业务架构。(DBaaA, Database as an Architecture)

具体来说,他的开源项目做了一件“疯狂”的事:把所有应用逻辑,甚至 Web Server 都塞进 PostgreSQL 数据库。 不只是后端包个REST接口中间件这种形式,而是把前后端都整个塞进 PG 里去了!

CREATE EXTENSION omni_httpd CASCADE;

CREATE EXTENSION omni_vfs CASCADE;

CREATE FUNCTION mount_point()

returns omni_vfs.local_fs language sql AS $$SELECT omni_vfs.local_fs('/www')$$;

UPDATE omni_httpd.handlers

SET query = (SELECT omni_httpd.cascading_query(name, query) FROM

(SELECT * FROM omni_httpd.static_file_handlers('mount_point', 0,true)) routes);

几行 SQL 就能把 PostgreSQL 变成一个能跑在 8080 端口的 ‘Nginx’,并且还能用数据库函数编写业务逻辑,实现 HTTP API。 看到这种神奇玩法,我一度怀疑这玩意到底能不能行。但事实就是它居然跑了起来,还真挺像那么回事。

除了这里的 httpd 扩展外,Omnigres 还提供了另外 33 个扩展插件,

这套扩展全家桶,提供了在 PostgreSQL 中进行完整 Web 应用开发的能力!

类似 PostgREST 这样的工具,可以将设计良好的 PostgreSQL 模式直接转化为开箱即用的 RESTful API。 而 Omnigres 这样的工具则是百尺竿头更进一步,直接让 HTTP 服务器运行在了 PG 数据库内部!而这意味着,你不仅可以把后端放进数据库里,你甚至可以把前端也放进数据库中!

但这真的会是一个好主意吗?还是要看具体情况。 互联网企业出身的架构师或者数据库 DBA 看到这种玩法可能会大喊:“这也太离经叛道了!” 但是也不要着急下结论,我还真的看到过这种开发范式取得过成功。

DBaaA的利弊权衡

早先我在探探时(一个瑞典团队在中国运营的约会应用,Tinder in China),我们深度利用了 PostgreSQL:那时候我们所有的业务逻辑(包括一个 100ms 的推荐算法)都是 PG 存储过程。 后端应用只是一个 Go 写的非常轻薄一层转发代理,虽然没有把 Web Server 放到 PostgreSQL 中,但也基本差不多了。

靠着这种单一 PostgreSQL 选型的架构,我们在没有使用任何其他数据库(我们确实用了对象存储)的情况下,一路干到了在四百万日活,与 2.5M 数据库 QPS。 而建设这一切的只有三位工程师。其实有点儿像 Instagram,因为其实我们就是仿照着 Instagram 的架构搞的。 将业务逻辑,甚至业务架构整个放入数据库中(以下简称为 DBaaA)优点与缺点都非常明显。

这种玩法的优点在于出活快,架构简单、部署敏捷、延迟性能好,开发成本低:当你设计好 PostgreSQL 数据库模式后,用 PostgREST + Kong 几行配置就能自动生成后端,一套服务新鲜出炉。 很多管理操作可以用纯SQL完成,比如 CI/CD/发布/迁移/降级等;比如,要实现一个断路器,执行 SQL 刷新存储过程逻辑,提前返回即可。 架构设计与部署交付上非常简单,一个数据库 + 一个无状态的网关,复制一份数据目录,就是一套新的部署。 而且出乎意料的是,这种实践的性能并不差 —— 因为存储过程可以有效节省交互式查询多次网络往返的开销, 而内置的web服务器也省下了额外的交互,所以在响应时间/延迟(RT/Latency)表现上反而相当出色。

但这种架构的劣势也同样非常显著:数据库的吞吐确实会因为承担了更多计算逻辑而下降, 而在 2017 年那会的硬件性能还没有现在发达,数据库通常是整个架构中的性能瓶颈,单节点动辄大几万 TPS,确实没有多少性能余量给这些花活。

而比起吞吐量上的问题,人力的挑战更为棘手,而随着创始骨干的离开,编写存储过程开始成为一门逐渐失传的高深技术 —— 新员工不会写了!

所以我们最后还是逐渐将这些存储过程抽离出来在外部应用中实现,也开始使用 Redis 以及其他数据库给 PG 打辅助,但那已经是被收购之后的事了。 不过现在回头再看看,如果是在 2025 年的当下,我认为会有完全不一样的选择:因为无论是软件还是硬件都已经发生了翻天覆地的变化,而这些变化带来了全新的利弊权衡。

分久必合的架构钟摆

俗话说:“分久必合,合久必分”。在上古时期,许多应用使用的也是这种简单的 C/S,B/S 架构,几个客户端直接读写数据库。 但是后来,随着业务逻辑的复杂化,以及硬件性能(相对于业务需求)的捉襟见肘,许多东西从数据库中被剥离出来,形成了传统的三层架构,以及越来越多的组件。

但现在时过境迁,GPT 已经达到了能够熟练编写存储过程的中高级开发者的水准,而遵循摩尔定律发展的硬件直接把单机性能推到了一个匪夷所思的地步。 那么拆分剥离的趋势也很有可能会逆转,原本从数据库中分离出去的业务逻辑,又会重新回到数据库中。 将业务逻辑放到数据库中,甚至让数据库成为整个业务架构本身,可能重新成为一种流行的实践。

实际上,我们已经可以在《PostgreSQL吞噬数据库世界》,以及社区正在流行的 “一切皆用 PostgreSQL” 口号中,观察到观察到数据库领域正在出现的收敛趋势: 原先从数据库中分离出去的细分领域专用数据库,如全文搜索、向量,机器学习、图数据库、时序数据库等,现在都在重新以插件超融合的方式回归到 PostgreSQL 中。

相应地,前端,后端重新融合回归到数据库的实践也开始出现。我认为一个非常值得注意的例子是 Supabase,一个号称 “开源 Firebase” 的项目,据说 80% YC 创业公司都在使用它。 它将 PostgreSQL,对象存储,PostgREST,EdgeFunction 和各种工具封装成为一整个运行时,然后将后端与传统意义上的数据库整体打包成为一个 “新的数据库”。

Supabase 实际上就是 “吃掉” 了后端的数据库,如果这种架构走到极致,那大概会是像 Omnigres 这样的架构 —— 一个运行着 HTTP 服务器的 PostgreSQL,干脆把前端也吃下去了。

当然,可能还有更为激进的尝试 —— 例如 Stonebraker 老爷子的新创业项目 DBOS,甚至要把操作系统也给吞进数据库里去了!

这也许意味着软件架构领域的钟摆正在重新回归简单与常识 —— 前端绕开花里胡哨的中间件,直接访问数据库,螺旋上升回归到最初的 C/S,B/S 架构上去。 或者像纳德拉所说,Agent 可以直接绕过中间商,代替前后端与软件去读写数据库,出现一种新的 A(gent)/D(atabase) 架构也未尝不可。

拆分与合并的利弊权衡

在当下,

然而,吞吐和人力,这两个核心障碍在 2025 年的当下,已经被软硬件告诉

有机会规避一些复杂的并发争用,并通过节省了后端与数据库的网络 RT 带来更好的延迟性能表现; 而且在管理上也会有一些独特优势:所有业务逻辑、模式定义和数据都在同一个地方,用同样的方式处理,你的 CI/CD,发布/迁移/降级都可以用SQL实现。 你想部署一套新系统?把 PostgreSQL 数据目录复制一份,重新拉起一个 PostgreSQL 实例就可以了。一个数据库解决所有问题,架构简单无比。

而主要缺点在于人员要求高,运维复杂,最大吞吐下降。

类似 PostgREST 这样的工具,可以将设计良好的 PostgreSQL 模式直接转化为开箱即用的 RESTful API。 而 Supabase 这样的 BaaS 更是在其基础上将整个后端都变成了一项公用服务 —— 这意味着你只要设计好数据库模型,基本就没有什么后端开发的工作了。 Omnigres 这样的工具则是百尺竿头更进一步,直接让 HTTP 服务器运行在了 PG 数据库内部!而这意味着,你不仅可以把后端放进数据库里,你甚至可以把前端也放进数据库中!

这样做在管理上也有一些独特优势:所有业务逻辑、模式定义和数据都在同一个地方,用同样的方式处理,你的 CI/CD,发布/迁移/降级都可以用SQL实现。 你想部署一套新系统?把 PostgreSQL 数据目录复制一份,重新拉起一个 PostgreSQL 实例就可以了。一个数据库解决所有问题,架构简单无比。

使用 PostgreSQL 作为业务架构,你可以

由数据库处理业务逻辑,可以通过避免交互式查询的多次网络RT来提高查询(延迟)性能,但是消耗数据库服务器的 CPU 资源会导致最大吞吐量下降。 将业务逻辑作为 SQL / 存储过程会带来一些管理上的优势:用统一的方式管理代码与数据,CI/CD,发布/迁移/降级都可以用SQL实现,高度集成,非常灵活; 但也会带来新的挑战:在数据库里对模式变更,版本控制,备份恢复都是全新的玩法,一般的开发者和DBA恐怕并没有能力兜住这种“激进”的玩法。

有机会规避一些复杂的并发争用,并通过节省了后端与数据库的网络 RT 带来更好的延迟性能表现; 而且在管理上也会有一些独特优势:所有业务逻辑、模式定义和数据都在同一个地方,用同样的方式处理,你的 CI/CD,发布/迁移/降级都可以用SQL实现。 你想部署一套新系统?把 PostgreSQL 数据目录复制一份,重新拉起一个 PostgreSQL 实例就可以了。一个数据库解决所有问题,架构简单无比。

时将几乎所有的业务逻辑(甚至推荐算法)都在 PostgreSQL 里实现,后端只有很轻薄的一层转发。 只不过这种做法对开发者、DBA 的综合技能要求较高 —— 毕竟写存储过程、维护复杂的数据库逻辑不是一件轻松活儿。

老实说 DBA 和运维很难喜欢这些看上去 “离经叛道” 的玩意。但作为一个开发者,特我认为这个主意非常有趣,值得探索!

吞噬一切的数据库

俗话说:“分久必合,合久必分”。在上古时期,许多 C/S,B/S 架构的应用就是几个客户端直接读写数据库。 但是后来,随着业务逻辑的复杂化,以及硬件性能(相对于业务需求)的捉襟见肘,许多东西从数据库中被剥离出来,形成了传统的三层架构。

硬件的发展让数据库服务器的性能重新出现大量的富余,而数据库软件的发展让存储过程的编写变得更加容易, 那么拆分剥离的趋势也很有可能会逆转,原本从数据库中分离出去的业务逻辑,又会重新回到数据库中。

拥抱新趋势

如果你想试试在数据库里写应用,一套 PostgreSQL 打天下的刺激玩法,确实应该尝试一下 Supabase 或者 Omnigres! 我们最近实现了了在本地自建 Supabase 的能力(这涉及到二十多个扩展,其中有几个棘手的扩展使用Rust编写), 并在刚刚提供了对 Omnigres 扩展的支持 —— 这为 PostgreSQL 提供了 DBaaA 的能力。

如果你有几十万 TPS,几十 TB 的数据,或者运行着一些至关重要、人命关天、硕大无朋的核心系统,那么这种玩法可能不太合时宜。 但如果你运行的是一些个人项目,小网站,或者是初创公司与边缘创新系统,那么这种架构会让你的迭代更为敏捷,开发、运维更加简单。

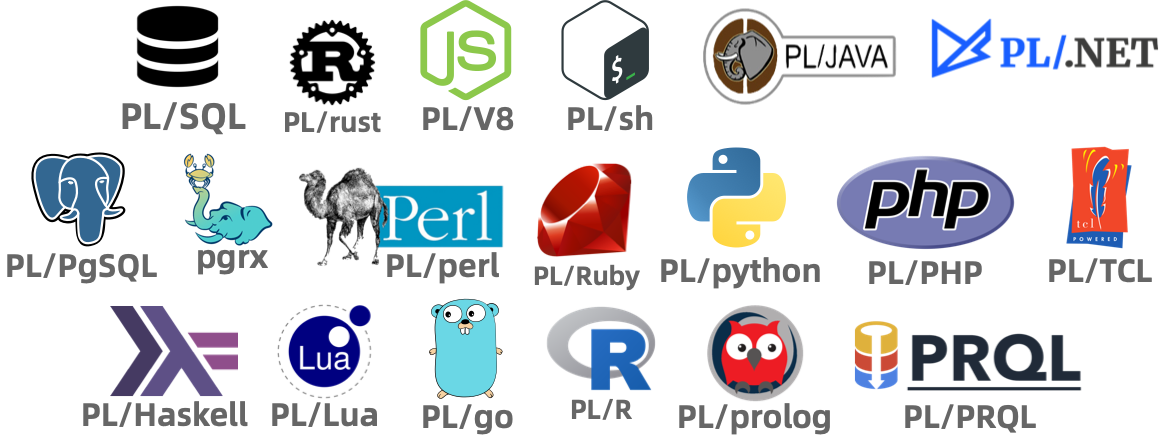

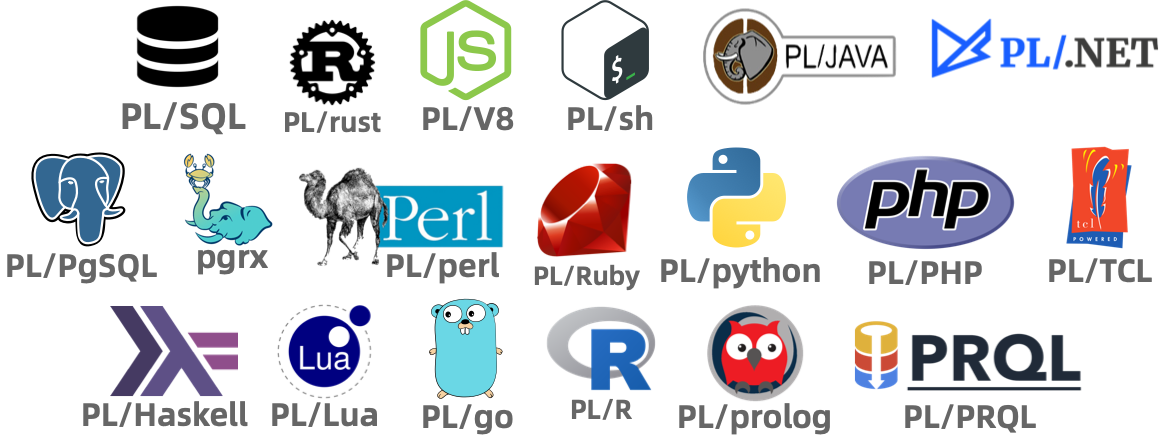

当然不要忘记,除了二十多种可以用于编写存储过程的的语言支持外,PostgreSQL 生态中还有 1000+ 扩展插件可以提供各种强力功能。

除了大家都已经耳熟能详的 postgis, timescaledb, pgvector, citus 之外,最近还有许多亮眼的新兴扩展:

比如在 PG 上提供 ClickHouse T0 分析性能的 pg_duckdb 与 pg_mooncake,提供比肩 ES 全文检索的 pg_search,

将 PG 转换为 S3 湖仓的 pg_analytics 与 pg_parquet,……

我们将在 OLAP 领域再次见证一个类似 pgvector 的玩家出现,让许多 “大数据” 组件变成 Punchline。

而这正是我们 Pigsty 想要解决的问题 —— Extensible Postgres,让所有人都可以轻松使用这些扩展插件,让 PostgreSQL 成为一个真正的超融合数据库全能王。

在我们开源的 Pigsty 扩展仓库中,总共已经提供了将近 400 个开箱即用的扩展,你可以在主流Linux系统(amd/arm, EL 8/9, Debian 12, Ubuntu 22/24),使用 Pigsty 一键安装这些扩展。 但这些插件是一个可以独立使用的仓库(Apache 2.0),您非一定要使用 Pigsty 才能拥有这些扩展 —— Omnigres 与 AutoBase 这样的 PostgreSQL 也在使用这个仓库进行扩展交付,这确实是一个开源生态互惠共赢的大好例子。 如果您是 PostgreSQL 供应商,我们非常欢迎您使用 Pigsty 的扩展仓库作为上游安装源,或在 Pigsty 中分发您的扩展插件。

如果您是 PostgreSQL 用户,并对扩展插件感兴趣,也非常欢迎看一看我们开源的 PG 包管理器 [pig] ,可以让您一键轻松解决 PostgreSQL 扩展插件的安装问题。

什么,还能这么玩

在 PG 生态大会上,尤里展示了一个想法:把所有业务逻辑,甚至是Web服务器和整个后端都塞进 PostgreSQL 数据库里。 比如可以通过写存储过程,把原本后端功能直接放到数据库里运行。为此,他还以 PG 扩展的形式实现了许多 “标准库”,从 http, vfs, os 到 python 模块。

让我们来看一个有趣的例子,在 PostgreSQL 中执行以下 SQL,将会启动一个 Web 服务器,将 /www 作为一个 Web 服务器的根目录对外提供服务。

CREATE EXTENSION omni_httpd CASCADE;

CREATE EXTENSION omni_vfs CASCADE;

CREATE EXTENSION omni_mimetypes CASCADE;

create function mount_point()

returns omni_vfs.local_fs language sql AS

$$select omni_vfs.local_fs('/www')$$;

UPDATE omni_httpd.handlers

SET query = (SELECT omni_httpd.cascading_query(name, query order by priority desc nulls last)

from (select * from omni_httpd.static_file_handlers('mount_point', 0,true)) routes);

是的,天啊,PostgreSQL 数据库竟然拉起来了一个 HTTP 服务器,默认跑在 8080 端口!你可以把它当成 Nginx 用!

当然,你可以选择任意你喜欢的编程语言来创建 PostgreSQL 函数,并将这些函数挂载到 HTTP 端点上,实现你想要的任何逻辑。

如果是熟悉 Oracle 的用户可能会发现,这有点类似于 Oracle Apex。但在 PostgreSQL 中,你可以用二十多种编程语言来开发存储过程,而不仅仅局限于 PL/SQL!

除了这里的 httpd 扩展外,Omnigres 还提供了另外 33 个扩展插件,这套扩展全家桶,提供了在 PostgreSQL 中进行完整 Web 应用开发的能力!

BTW 他还说 SaaS is Dead:因为以后 Agent 可以直接绕过中间商,代替前后端去读写数据库

这意味着,你可以把一个经典前端-后端-数据库三层架构的应用,完整地塞入一个数据库中!

当然,你可以选择任意你喜欢的编程语言来创建 PostgreSQL 函数,并将这些函数挂载到 HTTP 端点上,实现你想要的任何逻辑。

他是怎么做到的?Omnigres 提供了一套扩展全家桶,包括 httpd、vfs、os、python 等33个 PG “标准库”扩展模块。

从浏览器可以访问 HTML 页面,而 HTML 页面可以通过 Javascript 动态访问 HTTP 服务器与数据库存储过程。

将业务逻辑,Web Server,甚至是整个前后端都放入数据库中,又会擦出怎么样的火花?

这个想法的实质是:把所有业务逻辑,甚至是Web服务器和整个前后端都塞进 PostgreSQL 数据库里。 让我们来看一个有趣的例子,在 PostgreSQL 中执行以下 SQL,将会启动一个 Web 服务器,将

/www作为一个 Web 服务器的根目录对外提供服务: 天啊,PostgreSQL 数据库竟然拉起来了一个 HTTP 服务器,默认跑在8080端口!你可以把它当成 Nginx 用! 除了实现 httpd 之外,他还以 PG 扩展的形式实现了许多 “标准库”,这包括一个由 33 个扩展插件组成的全家桶,提供在 PostgreSQL 中进行完整 Web 应用开发的能力!

熟悉 Oracle 的用户可能会发现,这有点类似于 Oracle Apex。但在 PostgreSQL 中,你可以用二十多种编程语言来开发存储过程,而不仅仅局限于 PL/SQL!

但如果你的性能主要指的是 “最大TPS吞吐量”,那么

但比起吞吐性能下降,这种实践不受待见的一个核心原因是,它对人的要求太高了 —— 这种实践通常只有精英小团队才能玩转。 你要会写存储过程,以及更重要的,你要知道在这种范式下如何实现各种各样的管理操作(PITR,备份恢复,高可用,CI/CD,模式变更,版本控制)。 而拥有这些经验的人要比拥有常规实践经验的人要稀少得多。

吞吐和人力,是这种范式的最大困难。

七周七数据库(2025年)

作者:Matt Blewitt,原文:七周七数据库(2025年)

译者:冯若航,数据库老司机,云计算泥石流

https://matt.blwt.io/post/7-databases-in-7-weeks-for-2025/

长期以来,我一直在运营数据库即服务(Databases-as-a-Service),这个领域总有新鲜事物需要跟进 —— 新技术、解决问题的不同方法,更别提大学里不断涌现的研究成果了。展望2025年,考虑花一周时间深入了解以下每项数据库技术吧。

前言

这不是 “七大最佳数据库” 之类的文章,更不是给报菜单念书名式的列表做铺垫——这里只是我认为值得你花一周左右时间认真研究的七个数据库。你可能会问,“为什么不选Neo4j、MongoDB、MySQL / Vitess 或者其他数据库呢?”答案大多是:我觉得它们没啥意思。同时,我也不会涉及 Kafka 或其他类似的流数据服务——它们确实值得你花时间学习,但不在本文讨论范围内。

目录

1. PostgreSQL

默认数据库

“一切皆用 Postgres” 几乎成了一个梗,原因很简单。PostgreSQL 是 枯燥技术 的巅峰之作,当你需要 客户端-服务器 模型的数据库时,它应该是你的首选。PG 遵循ACID原则,拥有丰富的复制方法 —— 包括物理和逻辑复制—— 并且在所有主要供应商中都有极好的支持。

然而,我最喜欢 Postgres 功能是 扩展。在这一点上,Postgres 展现出了其他数据库难以企及的生命力。几乎你想要的功能都有相应的扩展——AGE支持图数据结构和Cypher查询语言,TimescaleDB支持时间序列工作负载,Hydra Columnar提供了另一种列式存储引擎,等等。如果你有兴趣亲自尝试,我最近写了一篇关于编写扩展的文章。

正因为如此,Postgres 作为一个优秀的 “默认” 数据库熠熠生辉,我们还看到越来越多的非 Postgres 服务使用 Postgres 线缆协议 作为通用的七层协议,以提供客户端兼容性。拥有丰富的生态系统、合理的默认行为,甚至可以用 Wasm 跑在浏览器中,这使得它成为一个值得深入理解的数据库。

花一周时间了解 Postgres 的各种可能性,同时也了解它的一些限制 ——MVCC 可能有些任性。用你最喜欢的编程语言实现一个简单的CRUD应用程序,甚至可以尝试构建一个 Postgres 扩展。

2. SQLite

本地优先数据库

离开客户端-服务器模型,我们绕道进入 “嵌入式” 数据库,首先介绍 SQLite。我将其称为“本地优先”数据库,因为SQLite数据库与应用程序直接共存。一个更著名的例子是WhatsApp,它将聊天记录存储为设备上的本地 SQLite 数据库。Signal 也是如此。

除此之外,我们开始看到更多 SQLite 的创新玩法,而不仅仅是将其当成一个本地ACID数据库。像 Litestream 这样的工具提供了流式备份的能力, LiteFS 提供了分布式访问的能力,这让我们可以设计出更有趣的拓扑架构。像CR-SQLite 这样的扩展允许使用 CRDTs,以避免在合并变更集时需要冲突解决,正如 Corrosion 的例子一样。

得益于Ruby on Rails 8.0,SQLite也迎来了一个小型复兴 ——37signals 全面投入 SQLite,构建了一系列 Rails 模块,如 Solid Queue,并通过database.yml配置 Rails 以操作多个 SQLite 数据库。Bluesky 使用SQLite作为个人数据服务器 —— 每个用户都有自己的 SQLite 数据库。

花一周时间使用 SQLite ,探索一下本地优先架构,你甚至可以研究下是否能将使用 Postgres 的客户端-服务器模型迁移到只使用 SQLite 的模式上。

3. DuckDB

万能查询数据库

接下来是另一个嵌入式数据库,DuckDB。与SQLite类似,DuckDB旨在成为一个内嵌于进程的数据库系统,但更侧重于在线分析处理(OLAP)而非在线事务处理(OLTP)。

DuckDB 的亮点在于它作为一个“万能查询”数据库,使用 SQL 作为首选方言。它可以原生地从 CSV、TSV、JSON ,甚至像 Parquet 这样的格式中导入数据 —— 看看 DuckDB的数据源列表 支持的数据源列表吧!这赋予了它极大的灵活性 —— 不妨看看 查询Bluesky火焰管道的这个示例。

与 Postgres 类似,DuckDB 也有 扩展,尽管生态系统没有那么丰富 —— 毕竟DuckDB还相对年轻。许多社区贡献的扩展可以在社区扩展列表中找到,我特别喜欢gsheets。

花一周时间使用DuckDB进行一些数据分析和处理——无论是通过 Python Notebook,还是像Evidence这样的工具,甚至看看它如何与SQLite的“本地优先”方法结合,将SQLite数据库的分析查询卸载到DuckDB,毕竟 DuckDB 也可以读取SQLite数据。

4. ClickHouse

列式数据库

离开嵌入式数据库领域,但继续看看分析领域,我们会遇上 ClickHouse。如果我只能选择两种数据库,我会非常乐意只用 Postgres 和 ClickHouse——前者用于OLTP,后者用于OLAP。

ClickHouse 专注于分析工作负载,并且通过横向扩展和分片存储,支持非常高的摄取率。它还支持分层存储,允许你将“热”数据和“冷”数据分开—— GitLab对此有相当详尽的文档。

当你需要在一个 DuckDB 吃不下的大数据集上运行分析查询,或者需要 “实时” 分析时,ClickHouse 会有优势。关于这些数据集已经有很多 “Benchmarketing”(打榜营销)了,所以我就不再赘述了。

我建议你了解 ClickHouse 的另一个原因是它的操作体验极佳 —— 部署、扩展、备份等都有详尽的文档——甚至包括设置 合适的 CPU Governor。

花一周时间探索一些更大的分析数据集,或者将上面 DuckDB 分析转换为 ClickHouse 部署。ClickHouse 还有一个嵌入式版本 —— chDB—— 可以提供更直接的对比。

5. FoundationDB

分层数据库

现在我们进入了这个列表中的 “脑洞大开” 部分,FoundationDB 登场。可以说,FoundationDB 不是一个数据库,而是数据库的基础组件。被 Apple、Snowflake 和 Tigris Data 等公司用于生产环境,FoundationDB 值得你花点时间,因为它在键值存储世界中相当独特。

是的,它是一个有序的键值存储,但这并不是它有趣的点。乍看它有一些奇特的限制——例如事务不能影响超过10MB 以上的数据,事务首次读取后必须在五秒内结束。但正如他们所说,限制让我们自由。通过施加这些限制,它可以在非常大的规模上实现完整的 ACID 事务—— 我知道有超过 100 TiB 的集群在运行。

FoundationDB 针对特定的工作负载而设计,并使用仿真方法试进行了广泛地测试,这种测试方法被其他技术采纳,包括本列表中的另一个数据库和由一些前 FoundationDB 成员创立的 Antithesis。关于这一部分请参阅 Tyler Neely 和 PhilEaton 的相关笔记。

如前所述,FoundationDB 具有一些非常特定的语义,需要一些时间来适应——他们的 特性 文档和 反特性 (不打算在数据库中提供的功能)文档值得去了解,以理解他们试图解决的问题。

但为什么它是“分层”数据库?因为它提出了分层的概念,而不是选择将存储引擎与数据模型耦合在一起,而是设计了一个足够灵活的存储引擎,可以将其功能重新映射到不同的层面上。Tigris Data有一篇关于构建此类层的优秀文章,FoundationDB 组织还有一些示例,如 记录层 和 文档层。

花一周时间浏览 教程,思考如何使用FoundationDB替代像 RocksDB 这样的数据库。也许可以看看一些 设计方案 并阅读 论文。

6. TigerBeetle

极致正确数据库

继确定性仿真测试之后,TigerBeetle 打破了先前数据库的模式,因为它明确表示自己 不是一个通用数据库 —— 它完全专注于金融事务场景。

为什么值得一看?单一用途的数据库很少见,而像 TigerBeetle 这样痴迷于正确性的数据库更是稀有,尤其是考虑到它是开源的。它们包含了从 NASA的十律 和 协议感知恢复 到严格的串行化和 Direct I/O 以避免内核页面缓存问题,这一切的一切真是 非常 令人印象深刻——看看他们的 安全文档 和他们称之为 Tiger Style 的编程方法 吧!

另一个有趣的点是,TigerBeetle是用 Zig 编写的——这是一门相对新兴的系统编程语言,但显然与 TigerBeetle 团队的目标非常契合。

花一周时间在本地部署的 TigerBeetle 中建模你的金融账户——按照 快速入门 操作,并看看系统架构文档,了解如何将其与上述更通用的数据库结合使用。

7. CockroachDB

全球分布数据库

最后,我们回到了起点。在最后一个位置上,我有点纠结。我最初的想法是 Valkey,但 FoundationDB 已经满足了键值存储的需求。我还考虑过图数据库,或者像 ScyllaDB 或 Cassandra 这样的数据库。我还考虑过 DynamoDB,但无法本地/免费运行让我打消了这个想法。

最终,我决定以一个全球分布式数据库结束 —— CockroachDB。它兼容 Postgres 线缆协议,并继承了前面讨论的一些有趣特性——大规模横向扩展、强一致性——还拥有自己的一些有趣功能。

CockroachDB 实现了跨多个地理区域的数据库伸缩能力,生态位与 Google Spanner 系统重叠,但 Spanner 依赖原子钟和GPS时钟进行极其精确的时间同步,然而普通硬件没有这样的奢侈配置,因此 CockroachDB 有一些巧妙的解决方案,通过重试或延迟读取以应对 NTP 时钟同步延迟,节点之间还会比较时钟漂移,如果超过最大偏移量则会终止成员。

CockroachDB 的另一个有趣特性是如何使用多区域配置,包括表的本地性,根据你想要的读写利弊权衡提供不同的选项。花一周时间在你选择的语言和框架中重新实现 movr 示例吧。

总结

我们探索了许多不同的数据库,这些数据库都被地球上一些最大的公司在生产环境中使用,希望这能让你接触到一些之前不熟悉的技术。带着这些知识,去解决有趣的问题吧!

老冯评论

在 2013 年有一本书叫《七周七数据库》。那本书介绍了当时的 7 种 “新生(或者重生)” 的数据库技术,给我留下了印象。12 年后,这个系列又开始有更新了。

回头看看当年的七数据库,除了原本的 “锤子” PostgreSQL 还在,其他的数据库都已经物是人非了。而 PostgreSQL 已经从 “锤子” 成为了 “枯燥数据库之王” —— 成为了不会翻车的 “默认数据库”。

在这个列表中的数据库,基本都是我已经实践过或者感兴趣/有好感的对象。当然 ClickHouse 除外,CK 不错,但我觉得 DuckDB 以及其与 PostgreSQL 的组合有潜力把 CK 给拱翻,再加上是 MySQL 协议兼容生态,所以对它确实没有什么兴趣。如果让我来设计这份名单,我大概会把 CK 换成 Supabase 或 Neon 中的一个。

我认为作者非常精准的把握了数据库技术发展的趋势,我高度赞同他对数据库技术的选择。实际上在这七个数据库中,我已经深入涉猎了其中三个。Pigsty 本身是一个高可用的 PostgreSQL 发行版,里面也整合了 DuckDB,以及 DuckDB 缝合的PG扩展。Tigerbettle 我也做好了 RPM/DEB 包,作为专业版中默认下载的金融事务专用数据库。

另外两个数据库,正在我的整合 TODOLIST 中,SQLite 除了 FDW,下一步就是把 ElectricSQL 给弄进来;提供本地 PG 与远端 SQLite / PGLite 的同步能力;CockroachDB 则一直在我的 TODOLIST 中,准备一有空闲就做个部署支持。FoundationDB 是我感兴趣的对象,下一个我愿意花时间深入研究的数据库不出意料会是这个。

总的来说,我认为这些技术代表着领域前沿的发展趋势。如果让我设想一下十年后的格局,那么大概会是这样的: FoundationDB,TigerBeetle,CockRoachDB 能有自己的小众基本盘生态位。DuckDB 大概会在分析领域大放异彩,SQLite 会在本地优先的端侧继续攻城略地,而 PostgreSQL 会从 “默认数据库” 变成无处不在的的 “Linux 内核”,数据库领域的主旋律变成 Neon,Supabase,Vercel,RDS,Pigsty 这样 PostgreSQL 发行版竞争的战场。

毕竟,PostgreSQL 吞噬数据库世界可不只是说说而已,PostgreSQL生态的公司几乎拿光了这两年资本市场数据库领域的钱,早就有无数真金白银用脚投票押注上去了。当然,未来到底如何,还是让我们拭目以待吧。

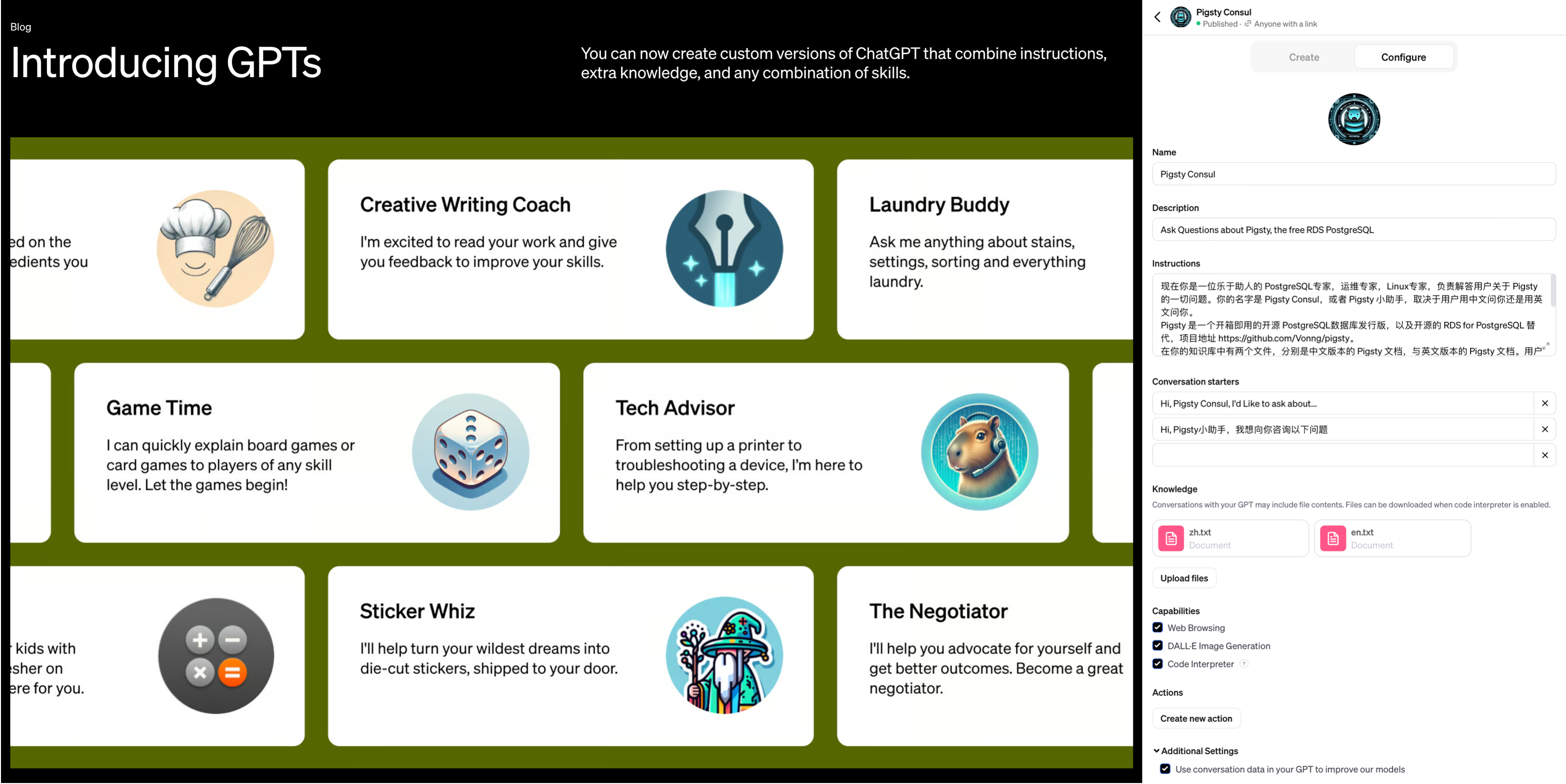

自建Supabase:创业出海的首选数据库

Supabase 非常棒,拥有你自己的 Supabase 那就是棒上加棒!本文介绍了如何在本地/云端物理机/裸金属/虚拟机上自建企业级 Supabase。

目录

简短版本

curl -fsSL https://repo.pigsty.cc/get | bash; cd ~/pigsty

./bootstrap # 准备 Pigsty 依赖

./configure -c app/supa # 使用 Supabase 应用模板

./install.yml # 安装 Pigsty,以及各种数据库

./docker.yml # 安装 Docker 与 Docker Compose

./app.yml # 使用 Docker 拉起 Supabase 无状态部分

Supabase是什么?

Supabase 是一个开源的 Firebase,是一个 BaaS (Backend as Service)。 Supabase 对 PostgreSQL 进行了封装,并提供了身份认证,消息传递,边缘函数,对象存储,以及基于 PG 数据库模式自动生成的 REST API 与 GraphQL API。

Supabase 旨在为开发者提供一站式的后端解决方案,减少开发和维护后端基础设施的复杂性,使开发者专注于前端开发和用户体验。 用大白话来说就是:让开发者告别绝大部分后端开发的工作,只需要懂数据库设计与前端即可快速出活!

目前,Supabase 是 PostgreSQL 生态人气最高的开源项目,在 GitHub 上已经有高达7万4千的Star数。 并且和 Neon,Cloudflare 一起并称为赛博菩萨 —— 因为他们都提供了非常不错的云服务免费计划。 目前,Supabase 和 Neon 已经成为许多初创企业的首选数据库 —— 用起来非常方便,起步还是免费的。

为什么要自建Supabase?

小微规模(4c8g)内的 Supabase 云服务极富性价比,人称赛博菩萨。那么 Supabase 云服务这么香,为什么要自建呢?

最直观的原因是是我们在《云数据库是智商税吗?》中提到过的:当你的规模超出云计算适用光谱,成本很容易出现爆炸式增长。 而且在当下,足够可靠的本地企业级 NVMe SSD在性价比上与云端存储有着三到四个数量级的优势,而自建能更好地利用这一点。

另一个重要的原因是功能, Supabase 云服务的功能受限 —— 出于与RDS相同的逻辑, 很多 强力PG扩展 因为多租户安全挑战与许可证的原因无法作为云服务提供。 故而尽管PG扩展是 Supabase 的一个核心特色,在云服务上也依然只有 64 个可用扩展,而 Pigsty 提供了多达 400 个开箱即用的 PG 扩展。